Atheroma / by W. Ainslie Hollis.

- Hollis, W. Ainslie (William Ainslie), 1839-1922

- Date:

- 1894-1896

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Atheroma / by W. Ainslie Hollis. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. The original may be consulted at The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

9/64 page 7

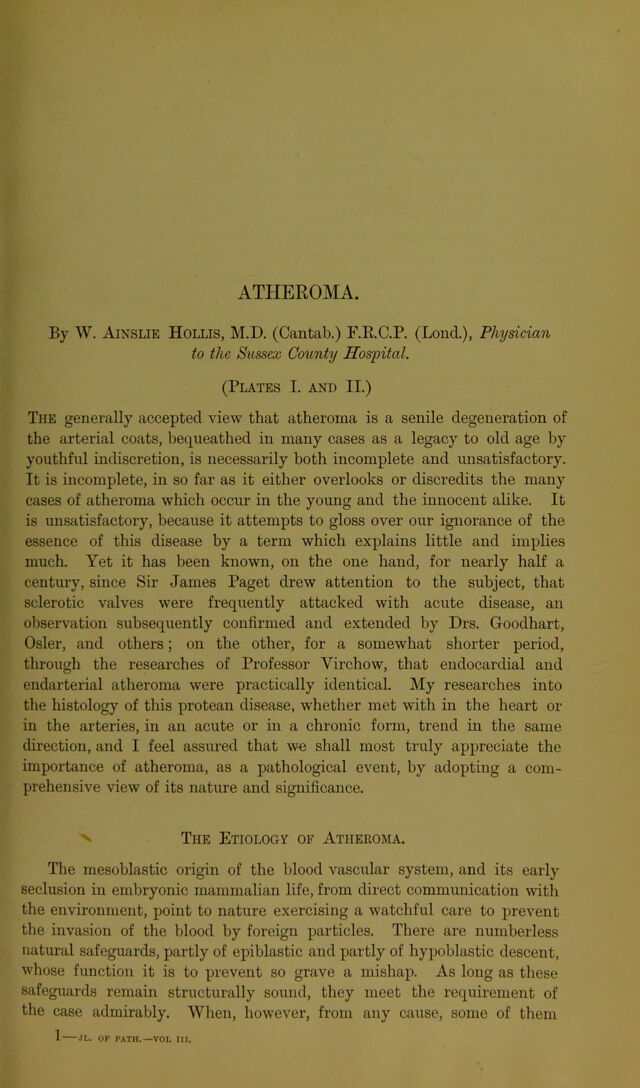

![of atheroma, preferably in certain vascular sites, and to certain structural peculiarities in connection therewith. If this statement of the case is haply the correct one, it may be advisable to inquire how these structural peculiarities react on the blood as it circulates past them, and whether the development of the disease can at any time be ascribed to these causes. A review of the sites commonly affected by atheroma will show that the favourite localities for outbreaks of this disease are conspicuous for some structural irregularities not genei’ally observable. As an illustration of my meaning, I shall mention the frequency with which the great aortic sinuses are attacked, on the one hand ; and, on the other, the bosses and ridges upon the cardiac valves and elsewhere. To take an example, the position of a Valsalvan sinus in its relations to the blood stream is unlike that of any other structure of the body. It is distended at each diastole by a backward thrust of the column of blood in the aorta, or in the pulmonary artery, as the case may be, on the closure of the sigmoid flaps. During the cardiac systole, on the other hand, the pocket is shut off from the blood stream.^ The surface must, therefore, be alternately swept by tumultuous eddies, as the blood closes the semilunar valves, or bathed in a layer of comparatively quiescent blood. Let me next take the case of a corpus arantii at the aortic oriflce. Here we have a distinct obstruction to the blood current, just where the bed is narrowest and the stream is consequently fastest. Atheroma, in my experience, most usually attacks that part of the cusp (in the closed valve), immediately external to the projecting body (Plate I. Figs. 1-4). Xow it is exactly at this spot that we might rightly expect a blood eddy once during each cardiac cycle. Again, there are certain portions of the arterial system, where dragging or pulling stresses must modify locally the effects of the circulation upon its elastic walls. I allude especially to the lines of attachment of the semilunar valves, and to the orifices of the smaller arteries; localities often affected with atheroma.- We are so accustomed to consider the blood as a liquid ph^’^siological unity, containing in health a definite percentage of semi-solid material, intimately commingled within it, that we too often overlook the wonder- ful precision with which the I’elative proportions of these constituents remain practically constant, and the means whereby this end is accom- plished. Among the physical processes for ensuring the intimate admixture of the corpuscular elements with the blood plasma doubtless the numerous intravascular eddies and back-currents play their part. However this may be, we find “ a little over five millions of corpuscles ^ According to Briicke, the .sigmoid flaps are closely applied to the arterial walls during cardiac systole ; Ceradini and others maintain that they float in an intermediate IKJsition. It matters not as regards the ])resent contention which of these views we accept. Probably both are partially coixect; Briicke explains what happens at the beginning of the systole, Ceradini the position of the valves subsequently. -Mr. Holmes sa)’s: “The aorta, popliteal, and axillary artery seem most liable to disease as being most constantly subject to stretching, and the latter to forcible rupture.”](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22382719_0011.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)