The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

102/1096 page 88

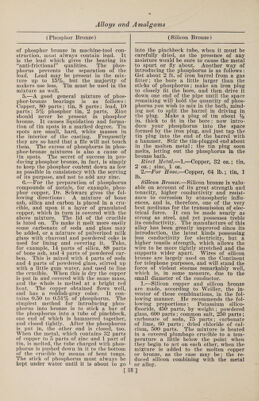

![(Phosphor Bronze) (Silicon Bronze) of phosphor bronze in machine-tool con¬ struction, must always contain lead. It is the lead which gives the bearing its “anti-frictional” qualities. The phos¬ phorus prevents the separation of the lead. Lead may be present in the mix¬ ture up to 15%, but the majority of makers use less. Tin must be used in the mixture as well. 5. —A good general mixture of phos¬ phor-bronze bearings is as follows: Copper, 80 parts; tin, 8 parts; lead, 10 parts; 5% phosphor tin, 2 parts. Zinc should never be present in phosphor bronze. It causes liquidation and forma¬ tion of tin spots in a marked degree. Tin spots are small, hard, white masses in the interior of the casting. Frequently they are so hard that a file will not touch them. The excess of phosphorus in phos¬ phor-bronze mixtures is also a cause of tin spots. The secret of success in pro¬ ducing phosphor bronze, in fact, is simply to keep the phosphor content down as low as possible in consistency with the serving of its purpose, and not to add any zinc. 6. —For the preparation of phosphorus compounds of metals, for example, phos¬ phor copper, Dr. Schwarz gives the fol¬ lowing directions: A mixture of bone ash, silica and carbon is placed in a cru¬ cible, and upon it a layer of granulated copper, which in turn is covered with the above mixture. The lid of the crucible is luted on. To make it melt more easily some carbonate of soda and glass may be added, or a mixture of pulverized milk glass with charcoal and powdered coke is used for lining and covering it. Take, for example, 14 parts of silica, 88 parts of bone ash, and 4 parts of powdered car¬ bon. This is mixed with 4 parts of soda and 4 parts of powdered glass, stirred up with a little gum water, and used to line the crucible. When this is dry the copper is put in and covered with the same mass, and the whole is melted at a bright red heat. The copper obtained flows well, and has a reddish-gray color. It con¬ tains 0.50 to 0.51% of phosphorus. The simplest method for introducing phos¬ phorus into bronze is to stick a bar of the phosphorus into a tube of pinchbeck, one end of which is hammered together, and closed tightly. After the phosphorus is put in, the other end is closed, too. When the metal, which contains 32 parts of copper to 5 parts of zinc and 1 part of tin, is melted, the tube charged with phos¬ phorus is pushed down in it to the bottom of the crucible by means of bent tongs. The stick of phosphorus must always be kept under water until it is about to go into the pinchbeck tube, when it must be carefully dried, as the presence of any moisture would be sure to cause the metal to spurt or fly about. Another way of introducing the phosphorus is as follows: Get about 2 ft. of iron barrel from a gas fitter; the bore a little larger than the sticks of phosphorus; make an iron plug to closely fit the bore, and then drive it down one end of the pipe until the space remaining will hold the quantity of phos¬ phorus you wish to mix in the bath, mind¬ ing not to split the barrel in driving in the plug. Make a plug of tin about % in. thick to fit in the bore; now intro¬ duce your phosphorus into the space formed by the iron plug, and just tap the tin plug into the end of the barrel with a hammer. Stir the tin-plugged end about in the molten metal; the tin plug soon melts, letting out the phosphorus in the bronze bath. Rivet Metal.—1.—Copper, 82 oz.; tin, 2 oz.; zinc, 1 oz. 2.—For Hose.—Copper, 64 lb.; tin, 1 lb. Silicon Bronze.—Silicon bronze is valu¬ able on account of its great strength and tenacity, higher conductivity and resist¬ ance to corrosion by atmospheric influ¬ ences, and is, therefore, one of the very best mediums for the transmission of elec¬ trical force. It can be made nearly as strong as steel, and yet possesses treble its conductivity. The manufacture of this alloy has been greatly improved since its introduction, the latest kinds possessing less conductivity for electricity, but a higher tensile strength, which allows the wire to be more tightly stretched and the supports wider apart. Wires of silicon bronze are largely used on the Continent for telephone purposes, and will stand the force of violent storms remarkably well, which is, in some measure, due to the small diameter of the conductor. 1.—Silicon copper and silicon bronze are made, according to Weiller, the in¬ ventor of these combinations, in the fol¬ lowing manner. He recommends the fol¬ lowing proportions: Potassium silico- fluoride, 450 parts, by weight; powdered glass, 600 parts; common salt, 250 parts; carbonate of soda, 75 parts; carbonate of lime, 60 parts; dried chloride of cal¬ cium, 500 parts. The mixture is heated in a covered plumbago crucible to a tem¬ perature a little below the point when they begin to act on each other, when the mixture is added to the molten copper or bronze, as the case may be; the re¬ duced silicon combining with the metal or alloy. [88]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0102.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)