The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

104/1096 page 90

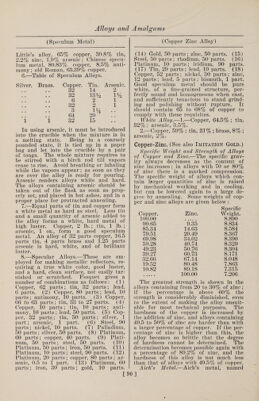

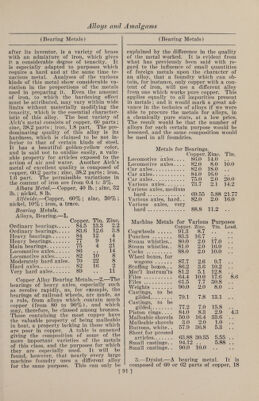

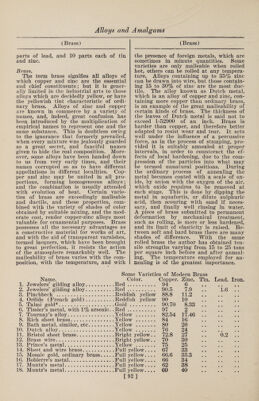

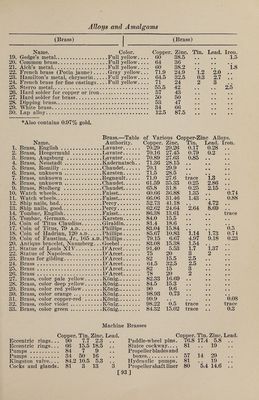

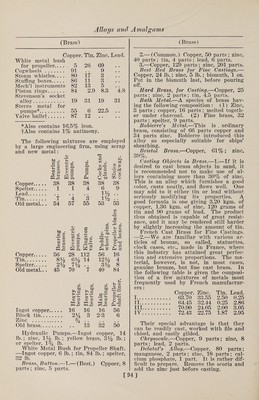

![(Speculum Metal) Little’s alloy, 65% copper, 30.8% tin, 2.2% zinc, 1.9% arsenic ; Chinese specu¬ lum metal, 80.83% copper, 8.5% anti¬ mony ; old Roman, 63.39% copper. 6.—Table of Speculum Alloys. Silver. Brass. Copper. Tin. Arsenic. 32 14 2 32 13y2 1% 6 2 1 32 2 1 3 1% • • 64 29 • • 1 1 32 15 • • In using arsenic, it must be introduced into the crucible when the mixture is in a melting state. Being in a coarsely pounded state, it is tied up in a paper bag and let into the crucible by a pair of tongs. The whole mixture requires to be stirred with a birch rod till vapors cease to rise. Avoid breathing or inhaling while the vapors appear; as soon as they are over the alloy is ready for pouring. Arsenic renders alloys white and hard. The alloys containing arsenic should be taken out of the flask as soon as prop¬ erly set, and placed in hot ashes, and in a proper place for protracted annealing. 7. —Equal parts of tin and copper form a white metal as hard as steel. Less tin and a small quantity of arsenic added to the alloy forms a white, hard metal of high luster. Copper, 2 lb.; tin, 1 lb.; arsenic, 1 oz., form a good speculum metal. An alloy of 32 parts copper, 16.5 parts tin, 4 parts brass and 1.25 parts arsenic is hard, white, and of brilliant luster. 8. —Specular Alloys.—These are em¬ ployed for making metallic reflectors, re¬ quiring a true white color, good luster, and a hard, clean surface, not easily tar¬ nished or scratched. Fesquet gives a number of combinations as follows : (1) Copper, 62 parts; tin, 32 parts; lead, 6 parts. (2) Copper, 80 parts ; lead, 10 parts; antimony, 10 parts. (3) Copper, 66 to 63 parts; tin, 33 to 27 parts. (4) Copper, 10 parts; tin, 10 parts; anti¬ mony, 10 parts ; lead, 50 parts. (5) Cop¬ per, - 32 parts; tin, 50 parts; silver, 1 part; arsenic, 1 part. (6) Steel, 90 parts; nickel, 10 parts. (7) Palladium, 50 parts; silver, 50 parts. (8) Platinum, 60 parts; copper, 40 parts. (9) Plati¬ num, 50 parts; steel, 50 parts. (10) Platinum, 50 parts; iron, 50 parts. (11) Platinum, 10 parts; steel, 90 parts. (12) Platinum, 20 parts; copper, 80 parts ; ar¬ senic, 0.5 to 1 part. (13) Platinum, 60 parts; iron, 30 parts; gold, 10 parts. [ (Copper Zinc Alloy) (14) Gold, 50 parts; zinc, 50 parts. (15) Steel, 50 parts; rhodium, 50 parts. (16) Platinum, 10 parts; iridium, 90 parts. (17) Tin, 29 parts; lead, 19 parts. (18) Copper, 52 parts ; nickel, 30 parts; zinc, 12 parts ; lead, 5 parts ; bismuth, 1 part. Good speculum metal should be pure white, of a fine-grained structure, per¬ fectly sound and homogeneous when cast, and sufficiently tenacious to stand grind¬ ing and polishing without rupture. It should contain 65 to 68% of copper to comply with these requisites. White Alloy.—1.—Copper, 64.5% ; tin, 32% ; arsenic, 3.5%. 2.—Copper, 59% ; tin, 31% ; brass, 8% ; arsenic, 2%. Copper-Zinc. (See also Imitation Gold.) Specific Weight and Strength of Alloys of Copper and Zinc.—The specific grav¬ ity always decreases as the content of zinc increases ; in alloys with 70 or 80% of zinc there is a marked compression. The specific weight of alloys which con¬ tain larger quantities of zinc is raised by mechanical working and in cooling, but can be lowered again to a large de¬ gree by annealing. Some weights of cop¬ per and zinc alloys are given below : Copper. Zinc. Specific Weight. 100.00 8.890 90.65 9.35 8.834 85.34 14.63 8.584 79.51 20.49 8.367 69.98 34.02 8.390 59.28 40.74 8.329 49.23 50.76 8.304 39.27 60.73 8.171 32.66 67.14 S.048 19.52 80.48 7.863 10.82 89.18 7.315 100.00 7.206 The greatest strength is shown in the alloys containing from 20 to 30% of zinc; if the percentage is above 60% the strength is considerably diminished, even to the extent of making the alloy unsuit¬ able for most technical purposes. The hardness of the copper is increased by the addition of zinc, and alloys containing 49.5 to 50% of zinc are harder than with a larger percentage of copper. If the per¬ centage of zinc is higher than this, the alloy becomes so brittle that the degree of hardness cannot be determined. The determination becomes possible again with a percentage of 89.2% of zinc, and the hardness of this alloy is not much less than that of alloys with 49.5% of copper. Aich's Metal.—Aich’s metal, named ]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0104.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)