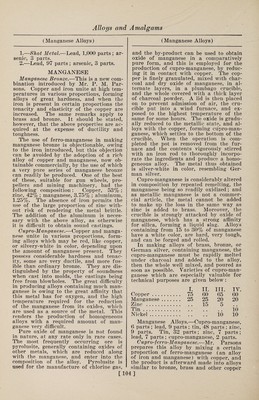

The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

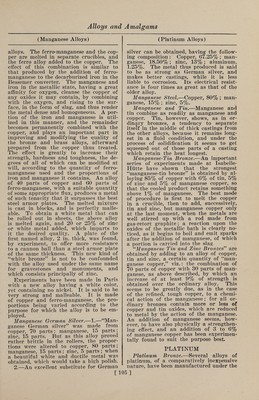

120/1096 page 106

![(Platinum Alloys) above name, and it has been claimed for them that they are indifferent to the ac¬ tion of air and water. They admit of a high polish, and retain their luster for a long time. The following are some of their compositions and uses : For table utensils, nickel, 90% ; platinum, 0.9% ; tin, 9%. For bells, nickel, 81.5% ; plati¬ num, 0.8% ; tin, 16% ; silver, 1.7%. For articles of luxury, nickel, 86.5% ; plati¬ num, 0.5% ; tin, 13%. For tubes for tele¬ scopes, etc., nickel, 71% ; platinum, 14.5% ; tin, 14.5%. For ornaments, nickel, 31.6% ; platinum, 3.2% ; brass, 65.2%. Cooper's Pen Metal.—This alloy is es¬ pecially well adapted to the manufacture of pens, on account of its great hardness, elasticity, and power of resistance to at¬ mospheric influences, and would certainly have superseded steel if it were possible to produce it more cheaply than is the case. The compositions most frequently used for pen metal are copper, 1 part; platinum, 4 parts; silver, 3 parts; or, copper, 12 parts; platinum, 50 parts; sil¬ ver, 36 parts. Pens have been manufac¬ tured consisting of several sections, each of a different alloy, suited to the special purpose of the part. Thus, for instance, the sides of the pen are made of the elastic composition just described; the. upper part is of an alloy of silver and platinum, and the point is made either of tiny cut rubies, or of an extremely hard alloy of osmium and iridium, joined to the body of the pen by melting in the flame of the oxyhydrogen blowpipe. The price of such pens, made of expensive materials, and at the cost of great labor, is, of course, exceedingly high, but their excellent qualities repay the extra ex¬ pense. They are not in the least affected by any kind of ink, are most durable, and can be used constantly for years with¬ out showing any signs of wear. The great hardness and resistance to the atmos¬ phere of Cooper’s alloys make them very suitable for manufacturing mathematical instruments where great precision is re¬ quired. It can scarcely be calculated how long a chronometer, for instance, whose wheels are constructed of this alloy, will run before showing any irregularity due to wear. In the construction of such in¬ struments the price of the material is not to be taken into account, since the cost of the labor in their manufacture so far exceeds this. Gold Alloys, Platinum and.—1.—Small quantities of platinum change the charac¬ teristics of gold in a considerable degree. With a very small percentage the color is noticeably lighter than that of pure (Platinum Alloys) gold, and the alloys are extremely elas¬ tic ; alloys containing more than 20% of platinum, however, almost entirely lose their elasticity. The melting point of the platinum-gold alloy is very high, and al¬ loys containing 70% of platinum can be fused only in the flame of oxyhydrogen gas, like platinum itself. Alloys with a smaller percentage of platinum can be pre¬ pared in furnaces, but require the strong¬ est white heat. In order to avoid the chance of an imperfect alloy from too low a temperature, it is always safer to fuse them with the oxyhydrogen flame. The alloys of platinum and gold have a some¬ what limited application ; those which con¬ tain from 5 to 10% of platinum are used for sheet and wire in the manufacture of artificial teeth. 2.—For Dental Purposes. II. 14 4 6 III. 10 6 '8 Platinum. 6 Gold. 2 Silver. 1 Palladium. 3.—Mirrors.—Alloy of gold and plati¬ num for coating. A solution of 500 grams of spongy platinum in 100 c. c. of a mixture of equal parts of hydrochloric and nitric acids is evaporated to dryness, and the dry residue, after powdering, di¬ gested with 2,000 grams of lavender es¬ sence, 100 grams of turpentine, and 25 grams of sulphureted turpentine rosins. The gold, 30 grams, is transformed into chloride, and this is dissolved in 1,000 c. c. of a mixture of equal parts of ether and wrnter. The mixture is well shaken, and ethereal solution added to the plati¬ num and left to evaporate spontaneously. The mixture receives afterward a charge of 50 grams of litharge and a like quan¬ tity of lead borate, and 100 grams of lavender oil are added to it, when it will be ready for coating the mirror, which has to be exposed to red heat until the composition is burnt in. Iridio-Platinum.—Platinum is capable of being united to most other metals, the alloys being, as a rule, more fusible than platinum itself. It occurs in nature in combination with a rare metal called iridium, with which it is often alloyed; the resulting metal is called iridio-plati- num, and though still malleable, is hard¬ er than platinum, and unattacked by aqua regia; it is also much less readily fusible than platinum itself. Silver is hardened, but rendered brittle, by being alloyed with very small quantities of platinum. [106] Platinum and Nickel.—According to Lampadius, equal parts of nickel and plat-](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0120.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)