The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

134/1096 page 120

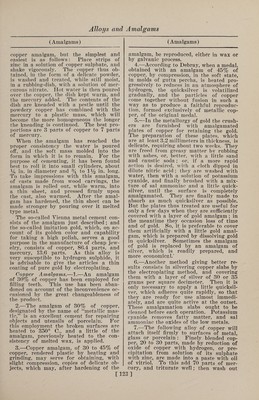

![(Amalgams) cific gravity of 1.85. Add to the paste thus formed 70 parts (by weight) of mercury, constantly stirring. When thor¬ oughly mixed, the amalgam must be care¬ fully rinsed in warm water to remove the acid, then laid aside to cool. In 10 or 12 hours it will be hard enough to scratch tin. When it is to be used, it should be heated to a temperature of 707° F. (375° C.), when it becomes as soft as wax by kneading it in an iron mortar. In this ductile state it can be spread upon any surface, to which, as it cools and hardens, it adheres very tenaciously. Tubania, Engestrum.—Copper, 4 parts ; antimony, 8 parts ; bismuth, 1 part; add¬ ed to tin, 100 parts. Tubania, English.—Brass (containing 7 parts of copper and 3 parts of zinc), 12 parts ; tin, 12 parts ; bismuth, 12 parts ; antimony, 12 parts. Tubania, German.—Copper, 0.4 part; tin, 3.2 parts; antimony, 42 parts. Tubania, Spanish.—1.—Iron and steel scraps, 24 parts; antimony, 48 parts; niter, 9 parts. The iron and steel are heated to whiteness, and the antimony and niter gradually added ; 2 oz. of this is alloyed with 1 lb. of tin ; a little ar¬ senic is an improvement. 2.—Iron or steel, 8 oz.; antimony, 16 oz.; niter, 3 oz. Melt and harden 8 oz. of tin with 1 oz. of this compound. AMALGAMS Mercury is well known to be the only metal which is liquid at ordinary tem¬ peratures. The best mercury is crystal¬ line in character, and of a silver-white color, freezing at —40° F. and boiling at 662°. When compounded with other met¬ als it forms alloys whose properties differ greatly according to the nature of the met¬ als used. In most cases the amalgams are at first liquid, and afterward become crystalline, any mercury in excess being separated. The amalgams offer an excel¬ lent opportunity for studying the behav¬ ior of the metals toward each other, the low temperature at which these com¬ pounds are formed making the examina¬ tion easier. If a metal is dissolved in mercury with an excess of the latter, a crystalline compound will soon separate from the originally liquid mass. This is the amalgam, whose proportions can be expressed according to fixed atomic weights, and easily obtained by removing the excess of mercury by pressure. Many amalgams are at first so soft that they can be kneaded in the hand like wax, but become hard and crystalline in time. These are especially adapted for filling (Amalgams) teeth, and much used for that purpose. Before the action of the galvanic current upon metallic solutions was known, by means of which certain metals can be separated in a pure state from solutions, and deposited upon a given surface, the amalgams were of great importance in gilding and silvering. The article was coated with the amalgam, and the mer¬ cury volatilized by heat, the gold or sil¬ ver remaining upon the surface as a co¬ herent coat. The process was called fire gilding. The chemical affinity of other metals for mercury varies greatly ; many combine with it very easily, others with such difficulty that an amalgam can only be obtained in a roundabout manner. Amalgams are of great interest theoreti¬ cally, and important to a general knowl¬ edge of alloys, but only a limited num¬ ber are actually employed in the indus¬ tries. Barium Amalgams. These can, by distillation, furnish ba¬ rium. It is one of the processes for pre¬ paring this metal, which, when thus ob¬ tained, almost always retains a little so¬ dium. Bismuth Amalgam. • Mercury and bismuth can be very easily combined by melting the latter and intro¬ ducing the mercury. The resulting amal¬ gam is very thinly fluid, and can be used for filling out very delicate molds. An addition of bismuth also makes other amalgams more thinly fluid. Such com¬ binations are cheaper than pure bismuth amalgam, and frequently used. Bismuth amalgams can be used for nearly all purposes for which cadmium amalgams are employed. On account of their fine luster, which equals that of silver, they are applied to special pur¬ poses, such as curved mirrors, and the preparation of anatomical specimens. For silvering glass globes or spherical and curved mirrors, the glass is heated carefully to the melting point of the amal¬ gam, and a small quantity of the amal¬ gam is poured into the cavity of the globe or convex mirror, and this is swung to and fro until it shows a reflecting sur¬ face. If the amalgam is not intended to remain upon the glass, the surface is rubbed with olive oil before pouring it in, and the oil carefully wiped off. An ex¬ tremely thin layer will remain, sufficient to prevent the amalgam from adhering. When it has cooled it can be removed by gently striking the glass upon a soft [120]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0134.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)