The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

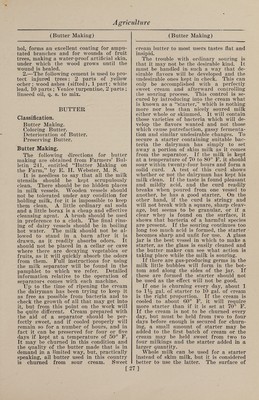

37/1096 page 23

![(Wasp and Bee Stings) • (Wounds) filled with cotton steeped in evaporated laudanum much comfort will be found. Wasp and Bee Stings. Carbolic acid in crystals, 1 dram; glycerine, 4 drams; distilled water, 1 dram. Dissolve the acid by the aid of a little heat. Two or three drops of the preparation should be placed on a little cotton wool, which, if possible, should be tied over the wound, so keeping the air away. Care should always be taken to see that the sting is not left in the flesh. That of the bee almost always is and keeps on injecting its poison. Other remedies are a solution of am¬ monia and bicarbonate of soda made into a paste with water and vinegar. Wounds. For systematic study wounds may be classed according to their direction, or depth, or locality, but for our purpose they may be arranged after the mode of their infliction: (1) Incised wounds, as cuts or incisions, including the wounds where portions of the body are clearly cut off; (2) punctured wounds, as stabs, pricks or punctures; (3) contused wounds, which are those combined with bruising or crushing of the divided por¬ tions ; (4) lacerated wounds, where the separation of tissue is effected by or com¬ bined with the tearing of them; (5) poi¬ soned wounds, including all wounds into which any poison, venom or virus is in¬ jected. Any of these wounds may be attended with excessive hemorrhage or pain or the presence of dead or foreign matter. As all wounds tend to present several com¬ mon features, a few words will be said about these before describing the distinc¬ tive characteristics of each. The first is hemorrhage (bleeding). This depends, as to quantity, upon sev¬ eral conditions, the chief of which is the size of the blood-vessels divided and to some extent upon the manner in which it has been done. A vessel divided with a sharp instrument presents a more favor¬ able outlet for the escape of blood than one that has been divided with a blunt or serrated instrument or one that has been torn across. Except in the first named, the minute fringes or roughness necessarily left around the edges of the vessel at the point of division retard the escape of blood and furnish points upon which deposits of blood, in the shape of clots, can take place. Hence, all other things being equal, an incised wound is usually attended with more hemorrhage than a contused or lacerated wound. The bleeding may be simply an oozing from the smallest blood-vessels, called the capillaries. This form of bleeding is not of much consequence and can easily be checked. The bleeding may be from a vein and is then called venous. The veins are the largest vessels which carry the blood back to the heart. The blood from them is purple and flows evenly, without any force. The bleeding may be from an artery and is then called arterial. The arteries are large distributing vessels which carry the blood from the heart to the extremi¬ ties. The blood from them is bright red and flows in pulsations or jets with some force. This is the most dangerous form of bleeding and the hardest to control. While we are not able sometimes to ascertain the kind of hemorrhage from a given wound, we should always try to determine it, for there may be consider¬ able difference in the treatment. There is always some pain present in a wound, and this varies largely with the location and extent of the injury. Often it is not nearly so much as we expect to find. In wounds of large size there is some shock, and when the wound is very ex¬ tensive and crushing the state of shock may be profound, even to unconscious¬ ness. In some people the mere sight of blood may be enough to cause fainting. This, of course, is very different from shock and much easier to treat. Nature stops bleeding by causing the blood to coagulate in little clots, which plug up the open mouths of the divided blood-vessels and prevent the further flow of blood. The smaller the blood-vessel and the more sluggish the current of blood therein, the more quickly this is done. Therefore this coagulation occurs first in the capillaries, next in the veins and last of all in the arteries. All that we can do is to aid nature in this by making the current of blood flow more slowly or by making the mouths of the vessels smaller. If the wound is small and the bleeding mostly capillary oozing, the part should be elevated, and firm pressure applied di¬ rectly to the wound, preferably through a clean wet cloth. A few minutes of this will usually be sufficient. If this does not suffice, we can try again, or we can apply water just as hot as can be borne with¬ out scalding, or we can apply pressure with a piece of ice wrapped in a clean handkerchief or a thin cloth. Heat and [23]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0037.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)