The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

58/1096 page 44

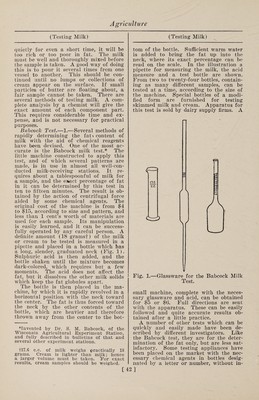

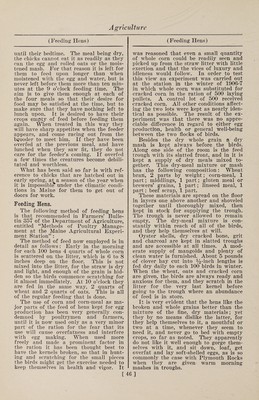

![The Quevenne lactometer is graduated from 15 to 40 and indicates directly the specific gravity. Thus at 60° F. it would read 32 in milk having a specific gravity of 1.032 and it would read 30.5 in milk having a specific gravity of 1.0305. The best forms of lactometers have a ther¬ mometer in the stem above the lactometer scale so that the temperature of the milk can be taken at the moment the reading is recorded. If the temperature is above or below 60° F. the lactometer reading must be corrected, and with the Quevenne lac¬ tometer the correction is made by adding 0.1 to the reading for each degree of tem¬ perature above 60° or subtracting 0.1 for each degree of temperature below 60°. Thus, if the Quevenne lactometer reading is 31 in milk having a temperature of 56°, the corrected reading would be 30.6 and the specific gravity at 60°, 1.0306. Accurate as these instruments are, they cannot do more than show specific grav¬ ity. If cream, which is lighter than milk, is removed, the specific gravity is in¬ creased ; and if water is added, the spe¬ cific gravity is decreased. Therefore if a sample of milk has a high specific gravity, skimming is suspected ; while if it has a low specific gravity,, watering is sus¬ pected. But if some cream is removed and water is added in proper proportion, the specific gravity may remain un¬ changed ; and this is one of the common¬ est ways of all for adulterating milk. If such fraud is extensively practiced it can be detected by the creamometer test or, more surely, by the Babcock fat test. A fair opinion of the value of milk, so far as its composition is concerned, can be formed from the percentage of fat, as the total solids of normal milk increase and decrease as the amount of fat is greater or less. If milk has been tam¬ pered with by watering, the percentage of fat is reduced in the same proportion as the other constituents, but in a greater proportion if the milk is skimmed. As fat is the part that the dishonest person tries to abstract, the purchaser is on the safe side if he judges of the quality of the milk by the fat which it contains. Many tests for the fat of milk have been pro¬ posed. The lactoscope and other optical methods are sometimes used to determine the fat or “oil,” but they are inaccurate, and especially so in the hands of one without large experience. Some of them depend on the color of the milk or on the fact that the more fat there is, the less light will pass through a thin layer. But as the color of milk is not an indi¬ cation of its richness, and the same amount of fat will retard more light when in small than when in large glob¬ ules, these methods may give incorrect re¬ sults and are therefore unreliable. 4. —Formaldehyde, Test for.—Deniges (Jour. Phar. Chim.) recommends the following method: To 10 c.cm. of milk add 1 c.cm. of fuchsine sulphurous acid, allow to stand five minutes ; then add 2 c.cm. of pure hydrochloric acid and shake. If formaldehyde is not present, the mix¬ ture remains yellowish-white; while if present, a blue-violet color is produced. This test will detect 0.02 gram of an¬ hydrous formaldehyde in one liter of milk. 5. —Heated Milk, Test for.—Wilkinson and Peters publish the following method of determining whether milk has or has not been heated : To 10 parts of the milk add 2 parts of a 4 per cent, alcoholic so¬ lution of benzidin, 2 parts of a 3 per cent, solution of hydrogen dioxide and a drop or two of acetic acid. A blue color¬ ation is instantly produced in raw milk, but not in milk that has been heated above 137° F. In mixtures of raw and cooked milk, 15 per cent, of raw milk gives a distinct, and even 10 per cent, a faint blue coloration ; but the addition of 5 per cent, of raw milk cannot be de¬ tected. If the hydrogen peroxide is omit¬ ted, the process may be used to detect the presence of that substance in the milk. 6. —Litmus Test.—H. D. Richmond (Chem. News) reports that litmus paper is entirely useless for testing the acidity of milk, this material often giving a re¬ action with perfectly fresh milk. Litmus paper may be either red, containing only the acid; or blue, containing besides the acid a varying amount of alkali, so that the paper may contain either all red par¬ ticles of litmus, all blue, or an inter¬ mediate mixture of the two. If these varieties of paper are applied to partially neutralized acids of various strength con¬ tradictory results may be obtained. Milk contains phosphoric acid in several states of neutralization. If milk is tested with a blue litmus, the paper having its acid entirely neutralized is more alkaline than the milk, and a portion of the alkali will pass into the liquid until equilibrium is restored; in consequence the litmus be¬ comes less alkaline and turns slightly red. If red litmus paper, which is more acid than the milk, is employed, alkali will pass from the liquid to the paper and turn it slightly blue. Litmus paper of some intermediate stage would not be affected. 7. —Water, Test for.—A German chem¬ ist furnishes a very simple procedure for [44]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0058.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)