The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

60/1096 page 46

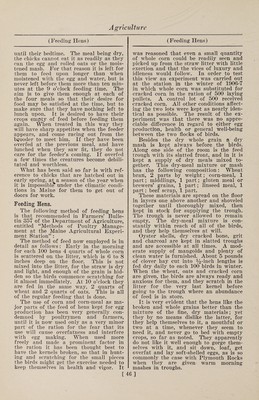

![(Feeding Hens) (Feeding Hens) until their bedtime. The meal being dry, the chicks cannot eat it as readily as they can the egg and rolled oats or the mois¬ tened mash. For that reason it is left for them to feed upon longer than when moistened with the egg and water, but is never left before them more than ten min¬ utes at the 9 o’clock feeding time. The aim is to give them enough at each of the four meals so that their desire for food may be satisfied at the time, but to make sure that they have nothing left to lunch upon. It is desired to have their crops empty of feed before feeding them again. When treated in this way they will have sharp appetites when the feeder appears, and come racing out from the brooder to meet him. If they have been overfed at the previous meal, and have lunched when they saw fit, they do not care for the feeder’s coming. If overfed a few times the creatures become debili¬ tated and worthless. What has been said so far is with ref¬ erence to chicks that are hatched out in early spring, at a season of the year when it is impossible under the climatic condi¬ tions in Maine for them to get out of doors for work. Feeding Hens. The following method of feeding hens is that recommended in Farmers’ Bulle¬ tin 857 of the Department of Agriculture, entitled “Methods of Poultry Manage¬ ment at the Maine Agricultural Experi¬ ment Station” : The method of feed now employed is in detail as follows : Early in the morning for each 100 hens 4 quarts of whole corn is scattered on the litter, which is 6 to 8 inches deep on the floor. This is not mixed into the litter, for the straw is dry and light, and enough of the grain is hid¬ den so the birds commence scratching for it almost immediately. At 10 o’clock they are fed in the same way, 2 quarts of wheat and 2 quarts of oats. This is all of the regular feeding that is done. The use of corn and corn-meal as ma¬ jor parts of the feed of hens kept for egg production has been very generally con¬ demned by poultrymen and farmers, until it is now used only as a very minor part of the ration for the fear that its use will cause overfatness and interfere with egg making. When used more freely and made a prominent factor in the ration it has been thought best to have the kernels broken, so that in hunt¬ ing and scratching for the small pieces the birds might get the exercise needed to keep themselves in health and vigor. It was reasoned that even a small quantity of whole corn could be readily seen and picked up from the straw litter with little exertion and that the vices of luxury and idleness would follow. In order to test this view an experiment was carried out at the station in the winter of 1906-7 in which whole corn was substituted for cracked corn in the ration of 500 laying pullets. A control lot of 500 received cracked corn. All other conditions affect¬ ing the two lots were kept as nearly iden¬ tical as possible. The result of the ex¬ periment was that there was no appre¬ ciable difference in regard to either egg production, health or general well-being between the two flocks of birds. Besides the dry whole grain a dry mash is kept always before the birds. Along one side of the room is the feed trough with its slatted front, and in it is kept a supply of dry meals mixed to¬ gether. This dry-meal mixture or mash has the following composition: Wheat bran, 2 parts by weight; corn-meal, 1 part; middlings, 1 part; gluten meal or brewers’ grains, 1 part; linseed meal, 1 part; beef scrap, 1 part. These materials are spread on the floor in layers one above another and shoveled together until thoroughly mixed, then kept in stock for supplying the trough. The trough is never allowed to remain empty. The dry-meal mixture is con¬ stantly within reach of all of the birds, and they help themselves at will. Oyster shells, dry cracked bone, grit and charcoal are kept in slatted troughs and are accessible at all times. A mod¬ erate supply of mangolds and plenty of clean water is furnished. About 5 pounds of clover hay cut into inch lengths is fed dry daily to each 100 birds in winter. When the wheat, oats and cracked corn are given, the birds are always ready and anxious for them, and they scratch in the litter for the very last kernel before going to the trough where an abundance of feed is in store. It is very evident that the hens like the broken and whole grains better than the mixture of the fine, dry materials; yet they by no means dislike the latter, for they help themselves to it, a mouthful or two at a time, whenever they seem to need it, and never go to bed with empty crops, so far as noted. They apparently do not like it well enough to gorge them¬ selves with it, and sit down, loaf, get overfat and lay soft-shelled eggs, as is so commonly the case with Plymouth Rocks when they are given warm morning mashes in troughs. [46]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0060.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)