The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

76/1096 page 62

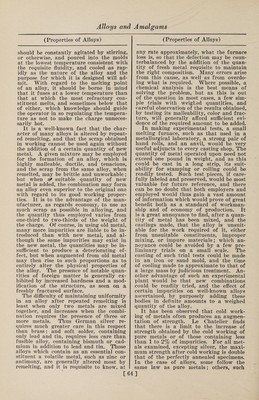

![(Properties of Alloys) age is formed of an alloy of copper, zinc and tin for similar reasons.” Alloys generally possess characteristics unshared by their component metals. Thus, copper and zinc form brass, which has a different density, hardness and color from either of its constituents. Whether the metals tend to unite in atomic pro¬ portions, or in any definite ratio, is still undetermined. The evidence afforded by the natural alloys of gold and silver, and by the phenomena accompanying the cool¬ ing of several alloys from the state of fusion, goes far to prove that such is the case. (Rudberg.) The subject is, however, one of considerable difficulty, as metals and metallic compounds are gen¬ erally soluble in each other, and unite by simple fusion and contact. That they do not combine indifferently with each other, but exercise a species of elective affinity not dissimilar to other bodies, is clearly shown by the homogeneity and su¬ perior quality of many alloys in which the constituent metals are in atomic propor¬ tion. The variation of the specific grav¬ ity and melting points of alloys from the mean of those ofi'their component metals, also affords strong evidence of a chemical change having taken place. Thus, alloys generally melt at lower temperatures than those required for their separate metals. They also usually possess more tenacity and hardness than the mean of their con¬ stituents. Matthiessen found that when weights are suspended to spirals of hard-drawn wire made of copper, silver, gold, or plati¬ num, they become nearly straightened when stretched by a moderate weight; but wires of equal dimensions, composed of copper-tin (12% of tin), silver-plati¬ num (36% of platinum), and gold-copper (84% of copper), scarcely undergo any permanent change in form when subjected to tension by the same weight. The same chemist gives the following approximative results upon the tenacity of certain metals and wires hard drawn through the same gauge (No. 23) : Cop¬ per, breaking strain for double wire, 25 to 30 lb.; tin, breaking strain for double wire, under 7 lb.; lead, breaking strain for double wire, under 7 lb.; tin-lead (20% lead), breaking strain for double wire, about 7 lb.; tin-copper (12% cop¬ per), breaking strain for double wire, about 7 lb.; copper-tin (12% tin), break¬ ing strain for double wire, about 80 to 90 lb.; gold, breaking strain for double wire, 20 to 25 lb.; gold-copper (8.4% copper), breaking strain for double wire, 70 to 75 lb.; silver, breaking strain for double (Properties of Alloys) wire, 45 to 50 lb.; platinum, breaking strain for double wire, 45 to 50 lb.; sil¬ ver-platinum (30% platinum), breaking strain for double wire, 75 to 80 lb. On the other hand, their malleability, ductil¬ ity, and power of resisting oxygen is gen¬ erally diminished. The alloy formed of two brittle metals is always brittle ; that of a brittle and a ductile metal, gener¬ ally so ; and even two ductile metals some¬ times unite to form a brittle compound. The alloys formed of metals having dif¬ ferent fusing points are usually malleable while cold, and brittle while hot. The action of the air on alloys is generally less than on their simple metals, unless the former are heated. A mix'ture of 1 part of tin and 3 parts of lead is scarcely acted on at common temperatures; but at a red heat it readily takes fire, and continues to burn for some time like a piece of bad turf. In like manner, a mix¬ ture of tin and zinc, when strongly heat¬ ed, decomposes both moist air and steam with almost fearful rapidity. The specific gravity of alloys is never the arithmetical mean of that of their constituents, as commonly taught; and in many cases considerable condensation or expansion occurs. When there is a strong affinity between two metals, the density of their alloy is generally greater than the calculated mean, and vice versa, as may be seen in the following list: Alloys the Density of which is Greater than the Mean of their Constituents.— Gold and zinc; gold and tin; gold and bismuth; gold and antimony; gold and cobalt; silver and zinc; silver and tin; silver and bismuth ; silver and antimony; copper and zinc; copper and tin; copper and palladium ; copper and bismuth ; lead and antimony; platinum and molybde¬ num ; palladium and bismuth. Alloys the Density of which is Less than the Mean of their Constituents.—* Gold and silver; gold and iron ; gold and lead; gold and copper ; gold and iridium ; gold and nickel; silver and copper; iron and bismuth; iron and antimony; iron and lead. Preparation and Properties of Alloys.—« The mode of procedure in the produc¬ tion of any alloy will be largely influ¬ enced by the nature of the metals to be operated upon. Some metals are volatile, and readily pass off as vapor when heated a few degrees above their melting points. Others have little tendency to vaporize, and may be raised to high temperatures without sensible volatilization. When a volatile metal has to be alloyed with a non-volatile metal, and the fusing points [62]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0076.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)