The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

79/1096 page 65

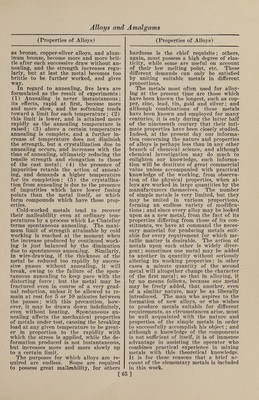

![(Properties of Alloys) as bronze, copper-silver alloys, and alum¬ inum bronze, become more and more brit¬ tle after each successive draw without an¬ nealing, and the strength increases regu¬ larly, but at last the metal becomes too brittle to be further worked, and gives way. In regard to annealing, five laws are formulated as the result of experiments: (1) Annealing is never instantaneous; its effects, rapid at first, become more and more slow, and the softening tends toward a limit for each temperature; (2) this limit is lower, and is attained more rapidly as the annealing temperature is raised; (3) above a certain temperature annealing is complete, and a further in¬ crease of temperature does not diminish the strength, but a crystallization due to annealing occurs, and increases with the time of annealing, ultimately reducing the tensile strength and elongation to those of the cast metal; (4) the presence of impurities retards the action of anneal¬ ing, and demands a higher temperature for its completion; (5) the crystalliza¬ tion from annealing is due to the presence of impurities which have lower fusing points than the metal itself, or which form compounds which have those prop¬ erties. Cold-worked metals tend to recover their malleability even at ordinary tem¬ peratures by a process which Le Chatelier terms spontaneous annealing. The maxi¬ mum limit of strength attainable by cold working is reached at the moment when the increase produced by continued work¬ ing is just balanced by the diminution due to spontaneous annealing. Similarly, in wire-drawing, if the thickness of the metal be reduced too rapidly by succes¬ sive passes without annealing, it will break, owing to the failure of the spon¬ taneous annealing to keep pace with the distorting force; but the metal may be fractured even in course of a very grad¬ ual reduction, unless it be allowed to re¬ main at rest for 5 or 10 minutes between the passes; with this precaution, how¬ ever, it may be drawn down indefinitely, even without heating. Spontaneous an¬ nealing affects the mechanical properties of metals under test, causing the breaking load at any given temperature to be great¬ er in proportion to the rapidity with which the stress is applied, while the de¬ formation produced is not instantaneous, but increases more and more slowly up to a certain limit. The purposes for which alloys are re¬ quired are endless. Some are required to possess great malleability, for others (Properties of Alloys) hardness is the chief requisite; others, again, must possess a high degree of elas¬ ticity, while some are useful on account of their low melting point, etc. These different demands can only be satisfied by uniting suitable metals in different proportions. The metals most often used for alloy¬ ing at the present time are those which have been known the longest, such as cop¬ per, zinc, lead, tin, gold and silver; and although combinations of these metals have been known and employed for many centuries, it is only during the latter half of the nineteenth century that their inti¬ mate properties have been closely studied. Indeed, at the present day our informa¬ tion concerning the nature and properties of alloys is perhaps less than in any other branch of chemical science, and although chemical investigation may do much to enlighten our knowledge, such informa¬ tion will be destitute of great commercial value unless accompanied with practical knowledge of the working, from observa¬ tion of the physical properties, when al¬ loys are worked in large quantities by the manufacturers themselves. The number of simple metals is very limited, but they may be united in various proportions, forming an endless variety of modifica¬ tions ; and since every alloy may be looked upon as a new metal, from the fact of its properties differing from those of its con¬ stituents, we have at command the neces¬ sary material for producing metals suit¬ able for every requirement for which me¬ tallic matter is desirable. The action of metals upon each other is widely diver¬ gent ; sometimes one metal may be added to another in quantity without seriously altering its working properties ; in other cases a minute quantity of the second metal will altogether change the character of the first metal; so that in alloying, it by no means follows, because one metal may be freely added, that another, even of a similar nature, may be as liberally introduced. The man who aspires to the formation of new alloys, or who wishes to produce metals suitable for different requirements, as circumstances arise, must be well acquainted with the nature and properties of the simple metals in order to successfully accomplish his object; and although a knowledge of the components is not sufficient of itself, it is of immense advantage in assisting the operator who combines practical experience in mixing metals with this theoretical knowledge. It is for these reasons that a brief ac¬ count of the elementary metals is included in this work. [65]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0079.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)