The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

80/1096 page 66

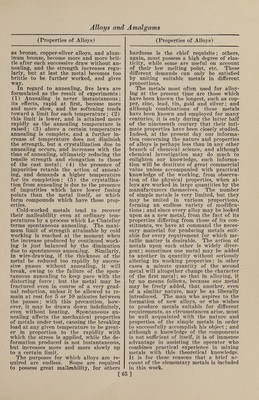

![(Properties of Alloys) In chemical combinations it is a well- known fact that elements always com¬ bine with other elements in definite pro¬ portions by weight, termed atomic weight, producing compounds of fixed and decided properties, so that the same compounds can be always relied upon to contain the same elements, united in the same pro¬ portions. The same law applies to the union of two metals, when such metals are chemically combined, and the same al¬ loy will always have properties identically the same, however it may be tested. Sev¬ eral experimenters have directed their at¬ tention to the mixing of metals according to their atomic weights, so as to obtain alloys of determined characteristic prop¬ erties, but up to the present time the number of such combinations of a useful character is very limited. They are by no means the ones most suited to the wants and requirements of industry. There is always one indispensable item, from the manufacturer’s point of view, which the chemist is not concerned with—- that is, the#cost of production—and how¬ ever nicely atomic proportions would suit the requirements of a given alloy, such an alloy would, in most cases, be useless unless the cost was consistent with the market value. The question, then, of cost must have consideration, and the propor¬ tions must, if possible, be made to fit in with commercial necessities. With regard to copper alloys, such as brass and bronze, the combinations which best exhibit the characters of chemical compounds are hard and brittle, and as copper alloys are much more widely used than any other, there is little inducement to encourage metallurgists to endeavor to alloy copper and zinc, or copper and tin, in atomic proportions, since malleability and tenac¬ ity are the properties most desired in these alloys. Again, color is the chief desideratum in many alloys, and this can¬ not be always obtained by mixing in atomic proportions, especially as it often happens that a very small addition of one of the constituents will alter thejshade of color so as to produce what is required. When it is desirable to add a non- metallic element to a metal or alloy, for the purpose of bringing about a certain result, very much greater care is gener¬ ally required in apportioning the quantity to be added than with a metal, as non- metals combine much more actively with metals than the metals do with each other, and a very small quantity of a non-metal will suffice to alter the properties of a metal or alloy. It is very surprising to note how, in some instances, a mere trace (Properties of Alloys) of another element will alter the proper¬ ties of a metal. For example, 1-2000 of carbon added to iron will convert it into mild steel; 1-1000 of phosphorus makes copper hot-short; 1-2000 part of tellu¬ rium in bismuth makes it minutely crys¬ talline ; 1-1000 part of bismuth in copper renders it exceedingly bad in quality for certain purposes. Lothar Meyer has shown that a remark¬ able relation exists between the “atomic volumes of the elements.” The rela¬ tive atomic volumes of the elements are found by dividing their atomic weights by their specific gravities. The atomic weight of lead is 207, and its specific gravity 11.45; 207 -f- 11.45 = 18, the atomic volume of lead. It would appear that the power of an element to produce weakness in a metal, when added in small quantitj7, is dependent on the atomic vol¬ ume of the impurity. Roberts-Austen tried the effect of various elements on pure gold, and found that when the body added had an atomic value equal to or less than that of gold the strength was little affected, and in some cases, as cop¬ per, for example, was increased; but when the element added had an atomic volume much greater than that of gold the strength, with two exceptions, was greatly diminished. Fusibility.—Some metals are almost in¬ fusible, and when heated to the highest heat in a crucible they refuse to melt and become fluid ; but any metal can be melted by combination with more fusible metals. Thus platinum, which is infusible with any ordinary heat, can be fused readilj when combined with zinc, tin or arsenic. This metal, by combination with arsenic, is rendered so fluid that it may be cast into any desired shape, and the arsenic may then be evaporated by a mild heat, leaving the platinum. Nickel, which barely fuses alone, will enter into com¬ bination with copper, forming German sil¬ ver, an alloy that is more fusible than nickel and less fusible than copper. The less fusible metals, when fused in contact with the more fusible metals, seem to dis¬ solve in the fusible metals; rather than melt, the surface of the metal is gradu¬ ally washed down, until the entire mass is dissolved or liquefied, and reduced to the state of alloy. Following are the melting points of the elements employed in alloys: Degrees Cent. Aluminum. 654.5 Antimony. 629.5 Arsenic . 450 [66]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0080.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)