The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

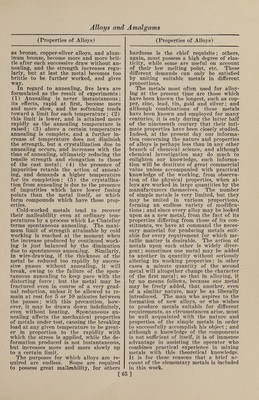

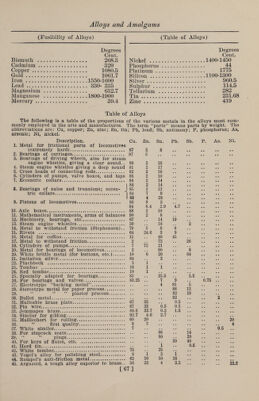

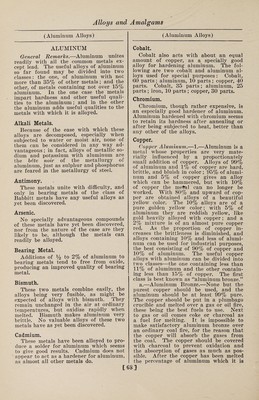

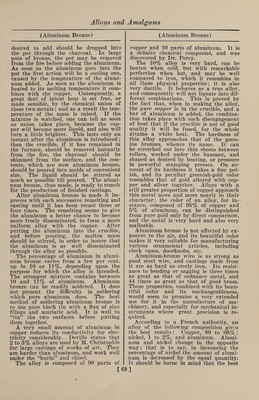

82/1096 page 68

![(Aluminum Alloys) ALUMINUM General Remarks.—Aluminum unites readily with all the common metals ex¬ cept lead. The useful alloys of aluminum so far found may be divided into two classes: the one, of aluminum with not more than 35% of other metals ; and the other, of metals containing not over 15% aluminum. In the one case the metals impart hardness and other useful quali¬ ties to the aluminum; and in the other the aluminum adds useful qualities to the metals with which it is alloyed. Alkali Metals. Because of the ease with which these alloys are decomposed, especially when subjected to water or moist air, none of them can be considered in any way ad¬ vantageous ; in fact, alloys of metallic so¬ dium and potassium with aluminum are the bete noir of the metallurgy of aluminum, just as sulphur and phosphorus are feared in the metallurgy of steel. Antimony. These metals unite with difficulty, and only in bearing metals of the class of Babbitt metals have any useful alloys as yet been discovered. Arsenic. No specially advantageous compounds of these metals have yet been discovered, nor from the nature of the case are they likely to be, although the metals can readily be alloyed. Bearing Metal. Additions of % to 2% of aluminum to bearing metals tend to free from oxide, producing an improved quality of bearing metal. Bismuth. These two metals combine easily, the alloys being very fusible, as might be expected of alloys with bismuth. They remain unchanged in the air at ordinary temperatures, but oxidize rapidly when melted. Bismuth makes aluminum very brittle. No valuable alloys of these two metals have as yet been discovered. Cadmium. These metals have been alloyed to pro¬ duce a solder for aluminum which seems to give good results. Cadmium does not appear to act as a hardener for aluminum, as almost all other metals do. [ (Aluminum Alloys) Cobalt. Cobalt also acts with about an equal amount of copper, as a specially good alloy for hardening aluminum. The fol¬ lowing are two cobalt and aluminum al¬ loys used for special purposes : Cobalt, 60 parts; aluminum, 10 parts; copper, 40 parts. Cobalt, 35 parts; aluminum, 25 parts ; iron, 10 parts ; copper, 30 parts. Chromium. Chromium, though rather expensive, is an especially good hardener of aluminum. Aluminum hardened with chromium seems to retain its hardness after annealing or after being subjected to heat, better than any other of the alloys. Copper. Copper Aluminum.—1.—Aluminum is a metal whose properties are very mate¬ rially influenced by a proportionately small addition of copper. Alloys of 99% of aluminum and 1% of copper are hard, brittle, and bluish in color ; 95% of alumi¬ num and 5% of copper gives an alloy which can be hammered, but with 10% of copper the metal can no longer be worked. With 80% and upward of cop¬ per are obtained alloys of a beautiful yellow color. The 10% alloys are of a pure golden yellow color; with 5% of aluminum they are reddish yellow, like gold heavily alloyed with copper; and a 2% mixture is of an almost pure copper reel. As the proportion of copper in¬ creases the brittleness is diminished, and alloys containing 10% and less of alumi¬ num can be used for industrial purposes, the best consisting of 90% of copper and 10% of aluminum. The useful copper alloys with aluminum can be divided into two classes—the one containing less than 11% of aluminum and the other contain¬ ing less than 15% of copper. The first class is best known as “aluminum bronze.” a.—Aluminum Bronze.—None but the purest copper should be used, and the aluminum should be at least 99% pure. The copper should be put in a plumbago crucible and melted over a gas or oil fire, these being the best fuels to use. Next to gas or oil comes coke or charcoal as a fuel for melting. It is impossible to make satisfactory aluminum bronze over an ordinary coal fire, for the reason that the copper will absorb the gases from the coal. The copper should be covered with charcoal to prevent oxidation and the absorption of gases as much as pos¬ sible. After the copper has been melted the percentage of aluminum which it is ]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0082.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)