The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

83/1096 page 69

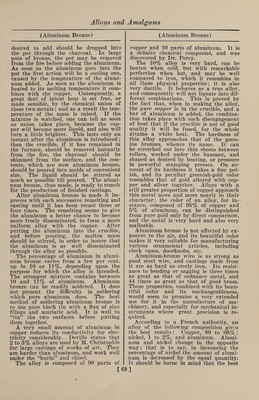

![(Aluminum Bronze) desired to add should be dropped into the pot through the charcoal. In large pots of bronze, the pot may be removed from the fire before adding the aluminum. As soon as the aluminum goes into the pot the first action will be a cooling one, caused by the temperature of the alumi¬ num added. As soon as the aluminum is heated to its melting temperature it com¬ bines with the copper. Consequently, a great deal of latent heat is set free, or made sensible, by the chemical union of these two metals ; and as a result the tem¬ perature of the mass is raised. If the mixture is watched, one can tell as soon as union takes place, because the cop¬ per will become more liquid, and also will turn a little brighter. This lasts only an instant after the aluminum is introduced ; then the crucible, if it has remained in the furnace, should be removed instantly from the fire, the charcoal should be skimmed from the surface, and the con¬ tents, which are now aluminum bronze, should be poured into molds of convenient size. The liquid should be stirred as much as possible till poured. The alumi¬ num bronze, thus made, is ready to remelt for the production of finished castings. After aluminum bronze is made it im¬ proves with each successive remelting and casting until it has been recast three or four times. The remelting seems to give the aluminum a better chance to become more freely disseminated, to form a more uniform alloy with the copper. After putting the aluminum into the crucible, and before pouring, the molten mass should be stirred, in order to insure that the aluminum is as well disseminated through the alloy as possible. The percentage of aluminum in alumi¬ num bronze varies from a few per cent, up t'o 10 or 11%, depending upon the purpose for which the alloy is intended. The strongest mixture contains between 10 and 11% of aluminum. Aluminum bronze can be readily soldered. It does not present the difficulty in soldering which pure aluminum does. The best method of soldering aluminum bronze is to use pure block tin with a flux of zinc filings and muriatic acid. It is well to “tin” the two surfaces before putting them together. A very small amount of aluminum in copper reduces its- conductivity for elec¬ tricity considerably. . Deville states that 2 to 3% alloys are used by M. Christophle for large castings of works of art. They are harder than aluminum, and work well under the “burin” and chisel. The alloy is composed of 90 parts of (Aluminum Bronze) copper and 10 parts of aluminum. It is a definite chemical compound, and was discovered by Dr. Percy. The 10% alloy is very hard, can be beaten when cold, but with remarkable perfection when hot, and may be well compared to iron, which it resembles in all these physical properties; it is also very ductile. It behaves as a true alloy, and consequently will not liquate into dif¬ ferent combinations. This is proved by the fact that, when in making the alloy, the pure copper is in the crucible, and a bar of aluminum is added, the combina¬ tion takes place with such disengagement of heat that if the crucible is not of good quality it will be fused, for the whole attains a wThite heat. The hardness of this alloy approaches that of the genu¬ ine bronzes, whence its name. It can be stretched out into thin sheets between rollers, worked under the hammer, and shaped as desired by beating, or pressure in powerful stamping presses. On ac¬ count of its hardness it takes a fine pol¬ ish, and its peculiar greenish-gold color resembles that of gold alloyed with cop¬ per and silver together. Alloys with a still greater proportion of copper approach this metal more and more nearly in their character; the color of an alloy, for in¬ stance, composed of 95% of copper and 5% of aluminum, can be distinguished from pure gold only by direct comparison, and the metal is very hard and also very malleable. Aluminum bronze is not affected by ex¬ posure to the air, and its beautiful color makes it very suitable for manufacturing various ornamental articles, including clock cases, doorknobs, etc. Aluminum-bronze wire is as strong as good steel wire, and castings made from it are as hard as steely iron. Its resist¬ ance to bending or sagging is three times as great as that of ordnance metal, and 44 times as great as that of good brass. These properties, combined with its beau¬ tiful color and its unchangeableness, would seem to promise a very extended use for it in the manufacture of ma¬ chinery, and especially for mechanical in¬ struments where great precision is re¬ quired. According to a French authority, an alloy of the following composition gives the best results: Copper, 89 to 98% ; nickel, 1 to 2%, and aluminum. Alumi¬ num and nickel change in the opposite way; that is to say, in increasing the percentage of nickel the amount of alumi¬ num is decreased by the equal quantity. Tt should be borne in mind that the best [69]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0083.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)