The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

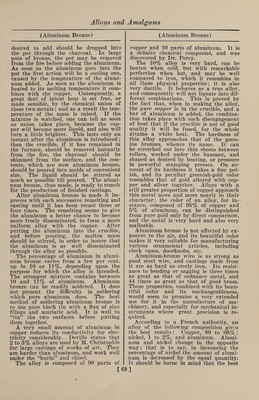

84/1096 page 70

![(Aluminum-Boron-Bronze) (Aluminum-Brass) ratio is: aluminum, 9.5% ; nickel, 1 to 1.5%, at most. In preparing the alloy, a deodorizing agent is added, viz.: phos¬ phorus to 0.5%, magnesium to 1.5%. The phosphorus should always be added in the form of phosphorus-copper or phosphor- aluminum of exactly determined percent¬ age. It is first added to the copper, then the aluminum and the nickel, and finally the magnesium, the last named at the moment of liquidity, are admixed. b.—Boron Bronze.—This alloy, or, more correctly speaking, aluminum-boron bronze, is brought about by the intro¬ duction of aluminum containing boron, not as aluminum boride, but existing as graphite does in cast iron. Commercially, this part of the process is accomplished by heating in a specially constructed oxy- hydrogen furnace an admixture of fluor¬ spar and vitrified boric anhydride, until the dense fumes of boron fluoride com¬ mence to appear. At this stage, ingots of aluminum are introduced into the liquid mass ; reduction at once takes place, with the formation of free boron, which dis¬ solves in the aluminum, rendering it crys¬ talline and somewhat brittle. When this so prepared aluminum is alloyed with copper, to the extent of from 5 to 10%, a bronze is obtained denser and more durable than ordinary aluminum bronze, and free from brittleness; but the most peculiar property is the perfectness with which it casts and melts; whereas, in the manufacture of aluminum bronze, one of the greatest difficulties is to insure a uniform mixture. Often a very difficultly fusible alloy of copper and aluminum is formed upon the surface of the already melted portion, and accompanied by su¬ perficial oxidation, thus obstinately refus¬ ing to alloy with the remainder. But in the case of the boron compound no such difficulties are met with, the alloy melt¬ ing perfectly, and at a lower temperature than when employing pure aluminum. Boron, in fact, seems to have been little studied, but it is evidently not so serious an enemy to cope with as its halogen silicon, which, when present in minute percentages only, determines the total ruin of the bronze with which it alloys; in other words, it stands almost entirely opposite to other elements, entering into the formation and forming compounds with the more refractory metals with the greatest ease; for instance, borides of iron, manganese, nickel, cobalt, etc., may be readily formed by the reduction of their accompanying borates in the pres¬ ence of carbon, while those of silver, cop¬ per, gold, etc., can only be formed by the introduction of elementary boron into the fused mass ; borides of the alkali met¬ als, and even calcium, barium, etc., have also been obtained, but boride of mercury still holds out. Aluminum-Copper.—2.—a.—The second class of copper-aluminum alloys embraces the aluminum casting alloys most appli¬ cable for general purposes. When alumi¬ num is alloyed with from 7 to 10% of copper a tough alloy is secured, the ten¬ sile strength of which will vary from 15,000‘to 20,000 lb. per square inch. This alloy has proved itself especially adapt¬ able to automobile work and to those castings submitted to severe shocks and stresses. Because of the nature of its constituents, an alloy of the above, or of similar composition, is not so liable to be “burnt” in the foundry as an alloy made up of more volatile constituents. The remainder of the range of copper- aluminum alloys, from 20% of copper up to over 85%, give crystalline and brittle grayish-white alloys of no use in the arts. After £0% of copper is reached the dis¬ tinctly red color of the copper begins to show itself. b.—Aluminum-Brass.—Aluminum-brass has an elastic limit of about 30,000 lb. per square inch ; an ultimate strength of from 40,000 to 50,000 lb. per square inch ; and an elongation of 3 to 10% in 8 in. Aluminum is used in brass in all pro¬ portions, from 1-10 of 1% to 10%. The best results are derived by introducing the aluminum, when possible, in the form of aluminized zinc (q. v.) This aluminized zinc is added in the same manner that the zinc is originally introduced into the copper, and in such proportions as will give the requisite amount of aluminum in the brass mixture. A 5% aluminized zinc is generally used when percentages of.less than 1% of aluminum are required ; and aluminized zinc of 10% is used when a greater percentage than 1% is required. The effect o faluminum in brass, added in this manner, in small quantities of less than 1%, is mainly to make the brass flow freely, and present a smooth surface, free from blowholes. When used in these quantities, from one-half to one- third more small patterns can be used on a gate than can be used without the pres¬ ence of aluminum, for this amount of aluminum gives to the brass such addi¬ tional fluidity as enables it to run more freely in the molds and for a greater dis¬ tance ; consequently more patterns can be used on a gate. In quantities of more than 1% the effect of the aluminum com¬ mences to be very perceptible, because it [70]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0084.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)