The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

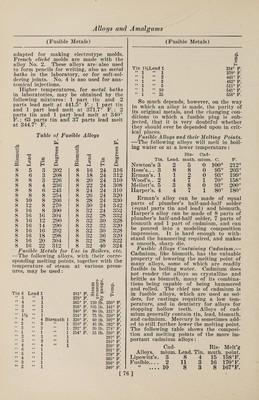

85/1096 page 71

![(Aluminum and Iron) imparts to the brass additional strength ; and this strength is increased directly as the percentage of aluminum is increased, up to about 10% ; 1% of aluminum in brass is very extensively used for elec¬ trical purposes, inasmuch as it makes a brass casting free from pinholes, and of greater strength than otherwise can be secured from the same grade of brass. It therefore follows that by the use of a small percentage of aluminum in brass a cheaper grade of brass can be used to do the same work, which otherwise would demand a better grade of brass. It should be noted that the presence of aluminum in these alloys lowers the point at which they become fluid, and that they are fluid at lower temperatures than either gun metal or ordinary brass mixtures ; there¬ fore, the average brass founder is very liable to overheat them. Great care must be taken to prevent this. Gold. Prof. W. C. Roberts-Austen has dis¬ covered a beautiful alloy, composed of 78 parts of gold and 22 parts of alumi- hum, which has a rich purple color. Indium. No valuable alloys of these metals have as yet been discovered. Iron. Aluminum combines with iron in all proportions. Few of the alloys, however, have yet proved of value, except those of small percentages of aluminum with steel, cast iron and wrought iron. Cast Iron.—In cast iron, from 1 to 2 lb. of aluminum per ton is put into the metal as it is being poured from the cupola or melting furnace. To soft gray No. 1 foundry iron it is doubtful if the metal does much good, except, perhaps, in the way of keeping the metal melted for a longer time; but where difficult castings are to be made, where much loss is occasioned by defective castings, or where the iron will not flow well, or give sound and strong castings, the ‘aluminum certainly in many cases allows better work to be done, and stronger and sound¬ er castings to be made, having a closer grain, and hence much easier tooled. The tendency of the aluminum is to change combined carbon to graphitic, and it les¬ sens the tendency of the metal to chill. Aluminum in proportions of 2% and over materially decreases the shrinkage of cast iron. Ferro-Aluminum.—This is the trade name given to alloys of from 5 to 10, or (Aluminum and Steel) even 20% of aluminum, added to iron. These alloys vary in quality, occasioned by the grade of steel or iron used in making them. Steel.—The amount of aluminum used is small, and, to give the best results, varies with the grade of steel, amount of occluded gases, temperature of molten metal, etc. Aluminum is usually added in proportions of from % to % lb. to 1 ton of steel. The aluminum is added either to the metal in the ladle, or, in the case of steel castings, with more econ¬ omy of aluminum, to the metal as it is being poured into the ingot molds. Until the proper percentage of alumi¬ num to add to any particular grade of steel has been determined, it is advisable to start with small amounts ; for instance, with 2 or 3 oz. to the ton, working up to the proportion that seems to give the best results. The special advantages to be gained by the use of aluminum in steel manu¬ facture are enumerated as follows: (1) The increase of soundness of tops of in¬ gots, and consequent decrease of scrap and other loss. (2) The quieting of the ebullition in molten steel, thereby allow¬ ing the successful pouring of “wild” heats from furnaces, ladles, etc. (3) The pre¬ vention of oxidation, thus increasing the homogeneity of the steel. (4) The in¬ crease of tensile strength of steel with¬ out decrease of the ductility. (5) The removal of any oxygen or oxides that there may be in the steel, the aluminum acting as a deodorizer in the same way as manganese does. Good steel has been made for electrical purposes, using alumi¬ num entirely in the place of manganese, to remove the oxidation from the molten steel and render it malleable. (6) The rendering of steel less liable to oxidation, because there is prevented the continued exposure of fresh surfaces of the molten steel in its ebullition in the molds after pouring. (7) The production of smoother surfaced castings and ingots of steel than it is possible to obtain without the use of aluminum. There are no such metals as “alumi¬ num steels,” in the same way that there are “nickel steels” and “chromium steels.” Aluminum is not a hardener of steel, and none of its alloys with steel has so far proved advantageous. It has been proved that the addition of aluminum to steel just before “teeming” causes the metal to lie quiet, and give off no appreciable quantity of gases, producing ingots with much sounder tops. There are two theo¬ ries to account for this: one, that the [71]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0085.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)