The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

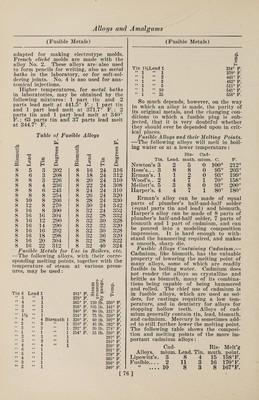

86/1096 page 72

![(Aluminum and Steel) aluminum decomposes these gases, and ab¬ sorbs the oxygen contained in them ; the other, is that aluminum greatly increases the solubility in the steel of the gases which are usually given off at the mo¬ ment of setting, thus forming blowholes and bubbles. Aluminum is the principal deoxidizer known to metallurgists, the next being- silicon. Their relative values are shown as follows: 100 parts, by weight, of oxy¬ gen will combine with 114 parts of alum¬ inum, or with 140 parts of silicon, or with 350 parts of manganese. This, how¬ ever, does not correctly express the value of aluminum as a deoxidizer of iron and steel, inasmuch as it has such a great affinity for oxygen that it will entirely disappear if there is any oxygen present, and will be found in the steel and iron only after all the oxygen has been ab¬ sorbed. This is not the case with either silicon or manganese. There is danger of adding too large a quantity of aluminum, in which case the metal will, set very solid, and will be liable to form deep “pipes” in the ingots. But successful results have been secured with varying kinds of steel by adding from % to % lb. of aluminum to 1 ton of steel. No difficulty has been experi¬ enced with the thorough mixing of the aluminum added to steel, as it seems to rapidly and uniformly permeate the steel without any special care being taken in stirring. This property adds to the homo¬ geneous alloying of nickel with steel as well, and the nickel-steel manufacturers use aluminum in addition to nickel for this purpose. If the metal be “wild” in the ladle, full of occluded gases, too hot, or oxidized, a larger proportion of alumi¬ num can be advantageously added. In casting steel ingots which are to be ham¬ mered or rolled, it has been found ad¬ visable to add from 2 to 4 oz. of alumi¬ num to 1 ton of steel. In the manufac¬ ture of steel castings, where the first de¬ sideratum is soundness of the castings and freedom from blowholes, and wffiere the excessive piping and contraction in cool¬ ing is provided for by large runners and a high and capacious fountain or “sinking head,” larger amounts of aluminum, up to 16, or even 32 oz. of aluminum to 1 ton of steel, are advantageously added. An alloy of aluminum and ferro-man- ganese has been patented. The addition of a small percentage of aluminum to the ferro-manganese renders the combined carbon in the manganese alloy graphitic, and throws it out of the molten mass. This permits the production of a ferro¬ (Aluminum and Magnesium) manganese very low in combined carbon, and particularly useful in the manufac¬ ture of low-carbon steel. Aside from the reduction of blowholes, and consequent greater soundness, the ad¬ dition of about 1 lb. of aluminum per ton of steel is of advantage where the steel is to be cast in heavy ingots which will receive only scant work. Here it seems to increase the ductility, as measured by the elongation and reduction of area of tensile test specimens, without materially altering the ultimate strength. The addi¬ tions of aluminum are, in many instances, made by throwing the metal into the ladle in pieces weighing a few ounoes each, as the steel is poured into it. But some manufacturers prefer to add the alumi¬ num in the form of ferro-aluminum ; in this case the alloy is first placed in the ladle, and, as the molten steel runs in, the alloy melts, and is diffused through the entire contents of the ladle. Wrought Iron.—The effect of aluminum in wrought iron is not very marked in the ordinary puddling process. It seems to add somewhat to the strength of the iron, but the amount is not of sufficient value to induce the general use of alumi¬ num for this purpose. The peculiar prop¬ erty of aluminum in reducing the long range of temperature between that at which wrought iron first softens and that at which it becomes fluid, is taken advan¬ tage of in the well-known Mitis process for making “wrought-iron castings.” It is for this that aluminum is most used in wrought iron at present. One per cent, of aluminum makes wrought iron more fluid at 2200° F. (which is about the melting point of cast iron) than it would be without it at 3500° F. In puddling iron an addition of 0.25% to the bath causes the charge to stiffen more quickly, and in the shingling process and in roll¬ ing the balls, to work much stiffer than usual. In one instance, where the ordi¬ nary iron averaged 22 tons tensile strength, with 12% elongation, the iron treated with aluminum showed over 30 tons tensile strength, with 22% elonga¬ tion. Lead. These metals unite only with great dif¬ ficulty, and no useful alloys have yet been discovered. Magnesium. The alloys of these light metals are interesting, because they are lighter than aluminum, and are equally as strong as the copper alloys of aluminum. On ac- [72]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0086.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)