The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

92/1096 page 78

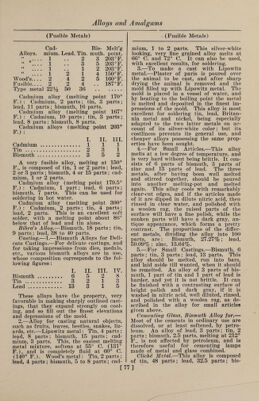

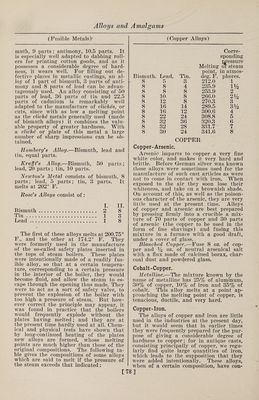

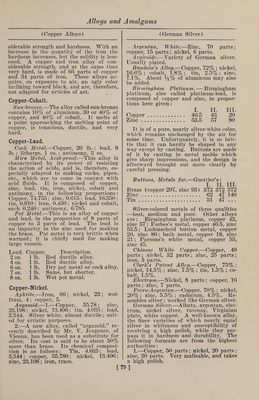

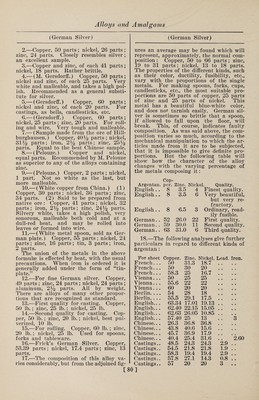

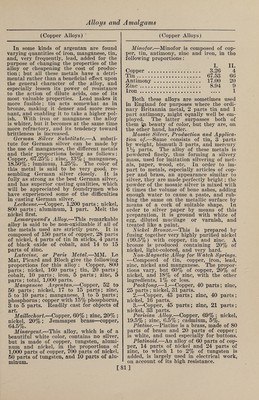

![(Fusible Metals) muth, 9 parts ; antimony, 10.5 parts. It is especially well adapted to dabbing roll¬ ers for printing cotton goods, and as it possesses a considerable degree of hard¬ ness, it wears well. For filling out de¬ fective places in metallic castings, an al¬ loy of 1 part of bismuth, 3 parts of anti¬ mony and 8 parts of lead can be advan¬ tageously used. An alloy consisting of 50 parts of lead, 36 parts of tin and 22.5 parts of cadmium is remarkably well adapted to the manufacture of cliches, or cuts, since with as low a melting point as the cliche metals generally used (made of bismuth alloys) it combines the valu¬ able property of greater hardness. With a cliche or plate of this metal a large number of sharp impressions can be ob¬ tained. Homberg's Alloy.—Bismuth, lead and tin, equal parts. Krafft's Alloy.—Bismuth, 50 parts; lead, 20 parts; tin, 10 parts. Newton's Metal consists of bismuth, 8 parts; lead, 5 parts; tin, 3 parts. It melts at 202° F. Rose's Alloys consist of: I. II. Bismuth. 2 8 Tin . ... 1 3 Lead. 1 8 The first of these alloys melts at 200.75° F., and the other at 174.2° F. They were formerly used in the manufacture of the so-called safety plates inserted in the tops of steam boilers. These plates were intentionally made of a readily fus¬ ible alloy, so that at a certain tempera¬ ture, corresponding to a certain pressure in the interior of the boiler, they would become fluid, and allow the steam to es¬ cape through the opening thus made. They were to act as a sort of safety valve, to prevent the explosion of the boiler with too high a pressure of steam. But how¬ ever correct the principle may appear, it was found in practice that the boilers would frequently explode without the plates having melted; and they are at the present time hardly used at all. Chem¬ ical and physical tests have shown that by long-continued heating of the plates new alloys are formed, whose melting points are much higher than those of the original compositions. The following ta¬ ble gives the compositions of some alloys which are said to melt if the pressure of the steam exceeds that indicated: [ (Copper Alloys) Corre- Bismuth. Lead. Tin. Melting point, deg. F. sponding pressure or steam in atmos¬ pheres. 8 5 3 212.0 1 8 8 4 235.9 iy2 8 8 8 253.9 2 8 10 8 266.0 2% 8 12 8 270.3 3 8 16 14 289.5 3y2 8 16 12 300.6 4 8 22 24 308.8 5 8 32 36 320.3 6 8 32 28 331.7 ' 7 8 30 24 341.6 8 Copper-Arsenic. COPPER Arsenic imparts to copper a very fine white color, and makes it very hard and brittle. Before German silver was known these alloys were sometimes used for the manufacture of such cast articles as were not to come in contact with iron. When exposed to the air they soon lose their whiteness, and take on a brownish shade. On account of this, as well as the poison¬ ous character of the arsenic, they are very little used at the present time. Alloys of copper and arsenic are best prepared by pressing firmly into a crucible a mix¬ ture of 70 parts of copper and 30 parts of arsenic (the copper to be used in the form of fine shavings) and fusing this mixture in a furnace with a good draft, under a cover of glass. Blanched Copper.—Fuse 8 oz. of cop¬ per and % oz. of neutral arsenical salt with a flux made of calcined borax, char¬ coal dust and powdered glass. Cobalt-Copper. Metalline.—The mixture known by the name of metalline has 25% of aluminum, 30% of copper, 10% of iron and 35% of cobalt. This alloy melts at a point ap¬ proaching the melting point of copper, is tenacious, ductile, and very hard. Copper-Iron. The alloys of copper and iron are little used in the industries at the present day, but it would seem that in earlier times they were frequently prepared for the pur¬ pose of giving a considerable degree of hardness to copper; for in antique casts, consisting principally of copper, we regu¬ larly find quite large quantities of iron, which leads to the supposition that they were added intentionally. These alloys, when of a certain composition, have con- ]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0092.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)