The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins.

- Albert A. Hopkins

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Scientific American cyclopedia of formulas : partly based upon the twenty-eighth edition of Scientific American cyclopedia of receipts, notes and queries 15,000 formulas / edited by Albert A. Hopkins. Source: Wellcome Collection.

99/1096 page 85

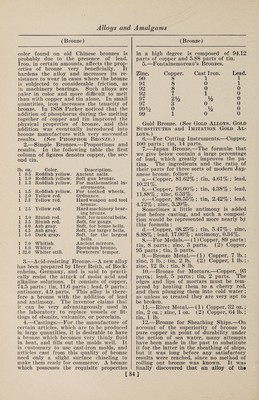

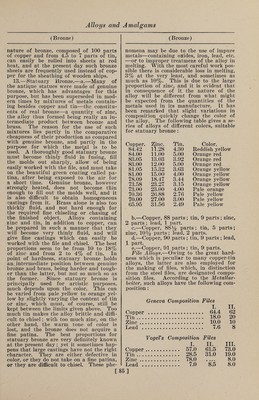

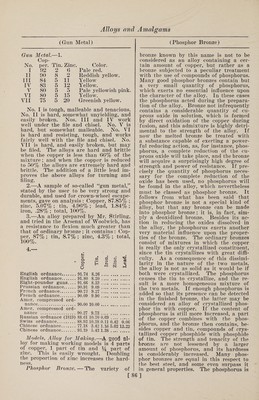

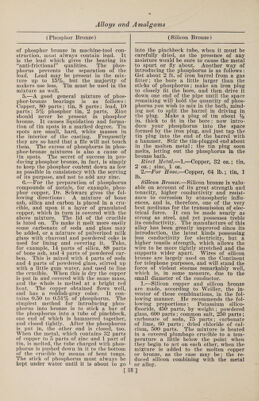

![nature of bronze, composed of 100 parts of copper and from 4.5 to 7 parts of tin, can easily be rolled into sheets at red heat, and at the present day such bronze sheets are frequently used instead of cop¬ per for the sheathing of wooden ships. 13.—Statuary Bronze.—a.—Many of the antique statues were made of genuine bronze, which has advantages for this purpose, but has been superseded in mod¬ ern times by mixtures of metals contain¬ ing besides copper and tin—the constitu¬ ents of real bronze—a quantity of zinc, the alloy thus formed being really an in¬ termediate product between bronze and brass. The reason for the use of such mixtures lies partly in the comparative cheapness of their production as compared with genuine bronze, and partly in the purpose for which the metal is to be used. A thoroughly good statuary bronze must become thinly fluid in fusing, fill the molds out sharply, allow of being easily worked with the file, and must take on the beautiful green coating called pa¬ tina, after being exposed to the air for a short time. Genuine bronze, however strongly heated, does not become tliin enough to fill out the molds well, and it is also difficult to obtain homogeneous -castings from it. Brass alone is also too thickly fluid, and not hard enough for the required fine chiseling or chasing of the finished object. Alloys containing zinc and tin, in addition to copper, can be prepared in such a manner that they will become very thinly fluid, and will give fine castings which can easily be worked with the file and chisel. The best proportions seem to be from 10 to 18% of zinc and from 2 to 4% of tin. In point of hardness, statuary bronze holds an intermediate position between genuine bronze and brass, being harder and tough¬ er than the latter, but not so much so as the former. Since statuary bronze is principally used for artistic purposes, much depends upon the color. This can be varied from pale yellow to orange yel¬ low by slightly varying the content of tin or zinc, which must, of course, still be kept between the limits given above. Too much tin makes the alloy brittle and diffi¬ cult to chisel; with too much zinc, on the other hand, the warm tone of color is lost, and the bronze does not acquire a fine patina. The best proportions for statuary bronze are very definitely known at the present day ; yet it sometimes hap¬ pens that large castings have not the right character. They are either defective in color, or they do not take on a fine patina, or they are difficult to chisel. These phe¬ nomena may be due to the use of impure metals—containing oxides, iron, lead, etc. —or to improper treatment of the alloy in melting. With the most careful work pos¬ sible there is considerable loss in melting, 3% at the very least, and sometimes as much as 10%. This is due to the large proportion of zinc, and it is evident that in consequence of it the nature of the alloy will be different from what might be expected from the quantities of the metals used in its manufacture. It has been remarked that slight variations in composition quickly change the color of the alloy. The following table gives a se¬ ries of alloys of different colors, suitable for statuary bronze: Copper. Zinc. Tin. Color. 84.42 11.28 4.30 Reddish yellow 84.00 11.00 5.00 Orange red 83.05 13.03 3.92 Orange red 83.00 12.00 5.00 Orange red 81.05 15.32 3.63 Orange yellow 81.00 15.00 4.00 Orange yellow 78.09 18.47 3.44 Orange yellow 73.58 23.27 3.15 Orange yellow 73.00 23.00 4.00 Pale orange 70.36 26.88 2.76 Pale yellow 70.00 27.00 3.00 Pale yellow 65.95 31.56 2.49 Pale yellow b. —Copper, 88 parts ; tin, 9 parts ; zinc, 2 parts ; lead, 1 part. c. —Copper, 88^ parts; tin, 5 parts; zinc, 10*4 parts ; lead, 2 parts. d. —Copper, 90 parts ; tin, 9 parts ; lead, 1 part. e. —Copper, 91 parts; tin, 9 parts. File Alloys.—Owing to the great hard¬ ness which is peculiar to many copper-tin alloys, the latter are also employed for the making of files, which, in distinction from the steel files, are designated compo¬ sition files. According to the Metallar- beiter, such alloys have the following com¬ position : Geneva Composition Files I. II. Copper . 64.4 62 Tin. 18.0 20 Zinc. 10.0 10 Lead . 7.6 8 VogeVs Composition Files I. II. III. Copper. 57.0 61.5 73.0 Tin. 28.5 31.0 19.0 Zinc. 78.0 .... 8.0 Lead . 7.0 8.5 8.0 [85]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31361523_0099.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)