Volume 1

Herodotus : the fourth, fifth, and sixth books / With introduction, notes, appendices, indices, maps by Reginald Walter Macan.

- Herodotus.

- Date:

- 1895

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Herodotus : the fourth, fifth, and sixth books / With introduction, notes, appendices, indices, maps by Reginald Walter Macan. Source: Wellcome Collection.

18/528 (page 10)

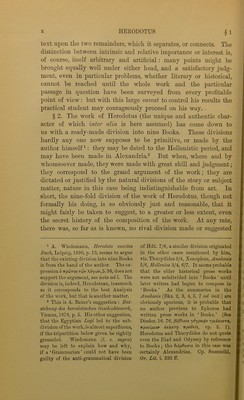

![§1 text upon the two remainders, which it separates, or connects. The distinction between intrinsic and relative imjDortance or interest is, of course, itself arbitrary and artificial: many points might be brought equally well under either head, and a satisfactory judg- ment, even in particular problems, whether literary or historical, cannot be reached until the whole work and the particular passage in question have been surveyed from every profitable point of view: but with this large caveat to control his results the practical student may courageously proceed on his way. § 2. The work of Herodotus (the unique and authentic char- acter of which inter alia is here assumed) has come down to us with a ready-made division into nine Books. These divisions hardly any one now supposes to be primitive, or made by the author himself ^: they may be dated to the Hellenistic period, and may have been made in Alexandria.^ But when, where and by whomsoever made, they were made with great skill and judgment; they correspond to the grand argument of the work; they are dictated or justified by the natural divisions of the story or subject matter, nature in this case being indistinguishable from art. In short, the nine-fold division of the work of Herodotus, though not formally his doing, is so obviously just and reasonable, that it might fairly be taken to suggest, to a greater or less extent, even the secret history of the composition of the work. At any rate, there was, so far as is known, no rival division made or suggested ^ A. Wiedemann, Herodots zweites Buoh, Leipzig, 1890, p. 13, seems to argue that the existing division into nine Books is from the hand of the author. The ex- pression 6 wpuiTos Twv \6yo}v, 5.36, does not support the argument, see note ad 1. The division is, indeed, Herodotean, inasmuch as it corresponds to the best Analysis of the work, hut that is another matter. 2 This is A. Bauer’s suggestion : Mit- stehung des Ticrodotischen GescMchtswerk, Vienna, 1878, p. 5. His other suggestion, that the Egyptian Logi led to the sub- division of the work, is almost superfluous, if the tripartition below given be rightlj’ grounded. Wiedemann {1. c. supi'a) may be left to explain how and why, if a ‘ Grammarian ’ could not have been guilty of the anti-grammatical division of Hdt. 7/8, a similar division originated in the other cases mentioned by him, viz. Thucydides 3/4, Xenophon, Aniabasis 5/6, Hellenics 3/4, 6/7. It seems probable that the older historical prose works were not subdivided into ‘ Books ’ until later writers had begun to compose in ‘Books.’ As the summaries in the Anabasis (Bks. 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 init,) are obviously spurious, it is probable that no author previous to Ephoros had written prose works in ‘ Books. ’ (See Diodor. 16. 76, /SljSXouy y^ypatpe rpidKovra, wpoolfiiov eKdcTj] wpodeLs, cp. 5. 1). Herodotus and Thucydides do not quote even the Iliad and Odyssey by reference to Books ; the dibpducm in this case was certainly Alexandrine. Cp. Susemihl, Or. Lit. i. 330 ff.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24872416_0001_0018.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)