Clinical pathology of the blood : a treatise on the general principles and special applications of hematology / by James Ewing.

- Ewing, James

- Date:

- 1904

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Clinical pathology of the blood : a treatise on the general principles and special applications of hematology / by James Ewing. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The University of Leeds Library. The original may be consulted at The University of Leeds Library.

38/570 page 34

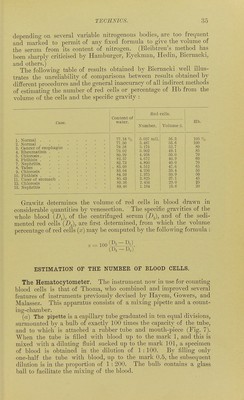

![cells except in leukemia, is determined by this method with accuracy sufficient for clinical purposes. The value of such information is, of course, quite evident. The further claim that the hematocrit may give more accurate estimates of the number of red cells than does the hematocytometer has not been confirmed. The volume of the red cells differs so markedly in both the chlorotic and the pernicious anemias that one cannot seriously consider the project of replacing the hematocytom- eter by the hematocrit. Only in the moderate secondary anemias, with little change in the size and Hb-content of the cells, can the volume of the red corpuscles yield reliable indications of their number. In cases of leukemia and of extreme leucocytosis so many leucocytes are entangled with the red cells that even the volume of the red cells is not accurately told, much less their number. Each of these instruments has its proper field to which it should be restricted, and as the hematocrit is not overexact in its immediate object, it is unscientific to introduce a second source of error, as is done in attempting to compute the number of red cells from their volume. It may be added that the value of the hematocrit in estimating the character and severity of an anemia has not yet been as fully recog- nized by clinicians as it deserves, possibly because more attention has been paid to the number of red cells than to their functional capacity. The reliability of the centrifuge in determining even the volume of the red cells has been denied principally by the brothers Bleibtreu, and by Bleibtreu and Wendelstadt. These observers devised another method of determining the volume of the red cells, which they claim gives more trustworthy results than are obtained by the hematocrit. They employed 0.6 per cent, salt solution to prevent coagulation, and allowed the blood to settle slowly. The nitrogen-content of the supernatant plasma was then determined by Kjeldahl's method, and from tables which these observers constructed the volume of the plasma, and hence that of the red cells, could be determined from the quantity of N obtained. While the results obtained with the hematocrit by several observers indicate that the normal volume of red cells varies between 40 and 66 per cent., Bleibtreu's method gave normal variations in cadaveric blood between 25.15 and 55.8 per cent. (Bleibtreu, Pfeiffer). v. Limbeclc obtained very low volumes Math Bleibtreu's method (24 to 28 per cent.), which he refers to the use of highly oxidized blood, in which he believes the red cells are reduced in volume. The lengthy discussion which has prevailed regarding the above points indicates that the volume of the red cells is subject to a considerable variety of changes, the origin and significance of which are little understood. It has been shown that in order to prevent N from leaving the red cells during sedimentation, the exact isotonic tension of the plasma must be determined in each instance, and a corresponding solution of salt used. The isotonic tension of plasma is rarely so low as 0.6 per cent. NaCl. Moreover, sup])osing that the red cells remain intact during sedi- mentation, the pathological variations in the N-content of the plasma.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21503886_0038.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)