Types of mankind, or, Ethnological researches, based upon the ancient monuments, paintings, sculptures, and crania of races, and upon their natural, geographical, philological and Biblical history / illustrated by selections from the inedited papers of Samuel George Morton and by additional contributions from L. Agassiz, W. Usher, and H.S. Patterson ; by J.C. Nott and Geo. R. Gliddon.

- Nott, Josiah C. (Josiah Clark), 1804-1873.

- Date:

- 1860

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Types of mankind, or, Ethnological researches, based upon the ancient monuments, paintings, sculptures, and crania of races, and upon their natural, geographical, philological and Biblical history / illustrated by selections from the inedited papers of Samuel George Morton and by additional contributions from L. Agassiz, W. Usher, and H.S. Patterson ; by J.C. Nott and Geo. R. Gliddon. Source: Wellcome Collection.

688/800 (page 632)

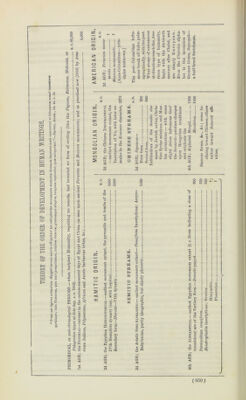

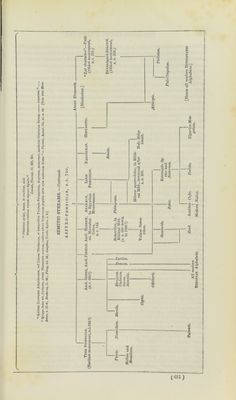

![Martin, Rask, Burnouf, Lassen, and Westergaard; the possession of the major portion of the folio plates and texts of Botta, Flandin and Coste, Layard, Texier, &c. ; and the inspection of what of Assyrian sculptures were in London and‘Paris during 1849: (221) .— our views upon Assyro-Babylonian writings take their departure and are derived from the series at foot, appended in the order of our studies.(222) Egyptian hieroglyphical discoveries had long ago revealed the fact that, as early at least as Thotmes III , of the XVIIIth dynasty, about the sixteenth century b. c., the Pha- raohs had overrun “ Naharina,” or Mesopotamia, with their armies. Accepted, like all new truths, with hesitation, since Rosellini’s promulgation of the data in 1832; or at first entirely denied by cuneatic discoverers, who claimed a primeval epoch for the sculptures of Nineveh and Babylon; nothing at this day is more positively fixed in historical science than these Egyptian conquests over “Nineveh” and “Babel,” at least three centuries before Derceto (the earliest monarch recorded in cuneiform inscriptions) lived; assuming Layard’s last view to be correct, (223) that he flourished about b. c. 1250. At foot we present the order in which an inquirer may investigate the discoveries that have finally set these ques- tions atrest; (224) while the following extracts from Rawlinson will render further doubts irrelevant: — “ That the employment of the Cuneiform character originated in Assyria, while the sys- tem of writing to which it was adapted was borrowed from Egypt, will hardly admit of ques- tion : . . . the whole structure of the Assyrian graphic system evidently betrays an Egyp- tian origin. . . . The whole system, indeed, of homophones is essentially Egyptian.” (225) It is upon such data that, without adducing other reasons derived from personal studies, we have made the earliest Semitic stream of our Table flow outwards from Egypt into ancient Mesopotamia — assigning the period of its Eastward flux, according to well-known conditions in Egyptian history, as bounded by the Xllth and XVIIIth dynasties: that is, between the twenty-second and sixteenth century b. c. ; — which age, placed parallel with Archbishop Usher’s scheme of biblical chronology, implies from a little before Abraham down to the birth of Moses. No Egyptologist will contest this view: the opinions of those who deny, without acquaintance with the works submitted, are “vox et praeterea nihil.” (221) Three Archaeological Lectures, on “Babylon, Nineveh, and Persepolis,” delivered before the Lyceum of the 2d Municipality at New Orleans; 6th, 9th, 13th April, 1852; by G. It. G. (222) Botta: Letlres d M. Mold; Paris, 1845; — De Longp£rier and De Saulcy, in Lev. Archeol.; 1844-1852; — Lowenstern; Essai de Dcchi,(frement del’ flcriture Assyrienne; Paris, 1845; — Botta: Sur Vferiture CunMforme; 1849; — Rawlinson: Tablet of Behistun; 1S46; — and Commentary on Cuneiform Inscriptions; 1S50; — Hincks: On the Three lands of Persepolitan Writing; Trans. R. Irish Acad., 1847; — Norris : Memoir on the Scythic Version of the Behistun Inscription; and Rawlinson’s communications; in Jour. R. Asiat. Soc., 1853; xv. part 1. Many other works upon this speciality, no less than upon the writings of every historical nation of antiquity, are cited in the manuscripts we suppress for lack of space. But, by anticipation of their future appearance, it would be injustice to an author “ qui a puise it des bonnes sources,” not to recommend earnestly to the sincere inquirer after truth, a perusal of the first and only work in the English language which has grasped this vast subject in a manner commensurate Avith the progress of science. It arrived at the Philadelphia Library, and was kindly pointed out to us by our accomplished friend Mr. Lloyd P. Smith, after our oavu “Table” was already stereotyped. We have read it with admiration; and although upon three points, the hieroglyphical, the cuneiform, and especially the Hebrew, we might suggest a few critical — that is to say, more rigidly chronological — sub- stitutions ; yet, upon the whole performance we are happy to offer the warm commendations of a fellow-student. The reader will find it, in the meanwhile, an excellent adjunct to our “Table”; and the following extracts, with an interlineary commentary, suffice to indicate that Mr. Humphrey’s views and our own differ upon but a single point: — “The Avorld has now possessed a purely alphabetic system of writing for 3000 years or more [say rather, about 300 years less], and iconograpliic systems for more than 3000 years longer [say, considerably more] There can be little doubt that the art of writing grew up independently in many countries having no communication with each other [entirely agreed]” : (vide Hf.nrt Noel Humphreys: The Origin and lb-ogress of the Art of Writing; London, 1853; pp. 1, 3). (223) Babylon; 2d Ex.; 1853; p. 623. (224) Letronne: La Civilisation f’gyptienne; pp. 1-55; Rxtrait de la Revue des Deux Mondcs; Feb., April, 1545; — Birch; Statistical Tablet of Karnac; — Obelisk of Thotmes III.; and on Two Cartouches found at Aim- roud; Trans. R. Soc. Lit., 1S46-’4S;—Gliddon: Otia; p. 103; — Layard: Nineveh; 1848; ii. pp. 153-235;— Sharpe, in Bonomi’s Nineveh; pp. ; — Layard: Babylon; 1853; pp. 153-159, 186-196, 2S0-2S2, 630; — and, particularly, Bircii: Annals of Thotmes III.; London Archaologia, xxxv., 1853; p. 160, &c. (225) Commentary; 1850; pp. 4-6.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24885307_0690.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)