Licence: In copyright

Credit: Mediaeval medicine / by G. Henslow. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. The original may be consulted at The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

5/12 (page 429)

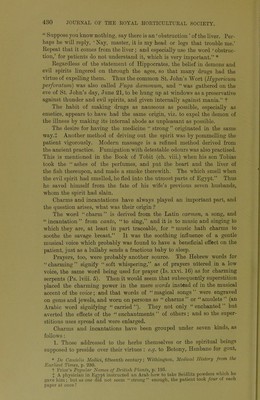

![conditions, and in this the school followed Hippocrates ; and Salerno was consequently called the “ Hippocratic city.” Perhaps Longfellow’s words— Joy, temperance, and repose Slam the door on the doctor’s nose were a free translation from the “ Regimen ” ; Si tibi deficiant medici, medici tibi fiant Hfec tria : mens hilaris, requies, moderata diteta. Medical books, i.e. apart from surgical works, of the fourteenth century consist of recipes, of which the follo\\dng peculiarities may be noticed. An immense number of plants were used for their supposed virtues, but very few are still retained in modern pharmacopoeias. The probable reason for their employment was, becmise a patient got well after using some drug, therefore that drug must have had the power to cure him, and as he got well when the same drug was used for a variety of complaints, therefore the said drug became a specific for a great variety of diseases. Thus we find Pliny giving the Cabbage credit as a remedy for some twenty-five complaints; but it is scarcely likely that it had curative powers for any one of them. Again, Betony is credited with some twenty virtues, among which it is said : “ Whoso beareth betony, the palsy shall not come at him ; if thou eat betony fasting, thou shalt not be a-venomed that day ; thou shalt not be drunk that day.” A peculiarity of many recipes is the extraordinary number of drugs included in one and the same prescription. Thus of a medicine called “ Save,” * in two recipes, one contained forty and the other fifty-one ingredients. It is not clear why it was so. Perhaps each had been good for wounds; so the physician thought one or two out of the number might be effectual; or perhaps the fee depended upon them, and he increased the number accordingly. This second suggestion finds its counterpart in Babylonian practice ; for Professor Sayce tells us : ” It is only occasionally that the names of special gods are introduced [into the penitential psalms], and then a long list of them is sometimes given, in the hope that among them might be the divinity whose anger had been excited, and whose wrath the suft’erer was eager to appease.” f Fees may, however, have been an underlying motive ; since as they copied ancient medicines they may have tried to follow the advice of Ben Solomon in his ‘Physician’s Guide’: “Treating the sick is like boring holes in pearls, and the physician • must act with caution lest he destroy the jewel committed to his charge.” “ Make your fees as high as possible, for services which cost little are little valued.” Another example: * This drug is mentioned by Chaucer in The Knightes Tale (lines 185.'l-56); ‘ To othre woundes, and to broken armes. Some hadde salves, and some hadde eharmes, Fermaoyes of herbes, and eek save They dronken ; for they wolde here lymes liave.’ t The lieligions of Ancient Egypt and Babgloma, \\ 417.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22397309_0005.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)