Volume 1

Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors.

- Date:

- 1888-1894

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

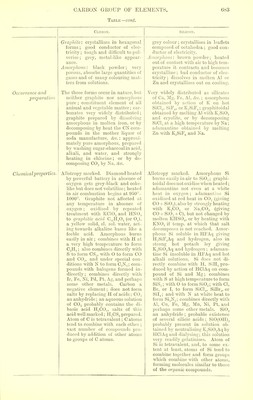

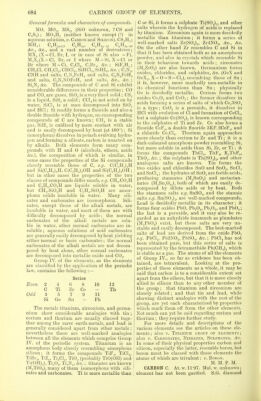

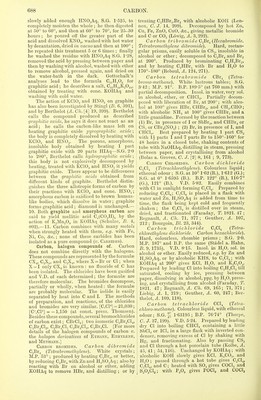

711/796 (page 685)

![is° 3-514 (Schrotter, Site. W. 63, (2nd pt.) 462), £ 3-518 (Baumhauer, Ar. N. 8, 1). S.G. graphite 2-11 to 2-26 (Kenngott, Brodie, Mene ; Site. IF. 13,469; A. 114, 7; C. R. 64, 104). S.G. amorphous charcoal 1-45 to 1-7 (v. Vio- lette, A. Ch. [3] 39, 291). S.G. hard gas-coke 2-356 (Marchand a. Meyer). S.H. about -5 at 1000° (v. infra). C.E. (diamond, linear at 40°) •00000118; (diamond, cub. at 49°) -00000354; (graphite, linear at 40°) -00000786; (Fizeau, C. B. 62, 1133 ; 68, 1125). /tn = 2-46, fiv = 2-479, for diamond (Schrauf, P. 112, 588). E.C. gra- phite, -082 (Hg at 0° = 1) [varies much for dif- ferent specimens] (Muraoka, W. 13, 307). E.C. hard gas-coke, -01 (Hg at 0° = 1) (Muraoka, I.e.). Crystalline form; diamond, regular octahedra and forms derived therefrom ; graphite, hexago- nal forms chiefly rhombohedral (Kenngott, Sitz. W. 13, 469) ; Nordenskiold (P. 96,100) observed monoclinic crystals in graphite from Finland. H.C. [C,0'] = 96,960 for amorphous C (Th. 1, 411); 93,350 for diamond, and 93,500 for graphite (Favre a. Silbermann, A. Ch. [3] 33, 414). Emission-spectrum observed by passing sparks through pure CO or CO., is characterised by a double line 6583 and 6577-5, three sharp lines 5150-5, 5144-2, 5133, and a band 4266 (Angstrom a. Thalen, Nov. Act. Ups. 9 [1875J). Besides these, and many other less marked, lines, Liveing a. Dewar describe the arc-spectrum as showing the following marked lines, 3919-3, 2837-2, 2836-3, 2511-9, 2509-9, 2296-5 {Pr. 30, 152, 494 ; 33, 403 ; 34, 123, 418). A very dif- ferent spectrum—the band-spectrum—is ob- served at the base of a candle or gas flame, also in cyanogen burnt in O, or by passing sparks through CN, CO at increased pressure, CS„ etc.; the most characteristic bands are 5633, 5164, and 4736. There has been much discussion as to whether this spectrum is that of C or of a hydrocarbon (v. B. A. 1880. 264). Three allo- tropic forms of carbon are known ; diamond, graphite, and amorphous carbon. The diamond was regarded by Newton as a combustible body because of its high refractive power; in 1694 diamond was burnt by the Florentine Academicians ; Lavoisier found that C02 is produced when diamond is burnt, and Davy showed that diamond is pure carbon. Lavoisier, about 1780, recognised that carbonic acid (then called fixed air) was a compound of O and the element which is the essential element of coal; to this element he gave the name car- bone. Graphite was long considered to be a kind of lead ; Scheele, in 1799, showed it to be closely related to coal; he regarded it as a com- pound of iron and carbon, but Kastner proved that the iron found in graphite was only an impurity, and that pure graphite is a form of carbon. Occurrence.—Carbon occurs as diamond and graphite, the former is pure, the latter some- times approximately pure, carbon ; many com- pounds of C occur in nature ; the chief are CO., in the air and all waters, mineral carbonates e.g. of Ca and Mg, and compounds with H, O, N, and sometimes P and S, in all animal and vegetable organisms. Diamonds are found in India, Borneo, Brazil, the Cape, &c.; graphite, in Cumberland, California, Siberia, &c. Berthelot (G. R. 73, 494) found graphite in a meteorite which fell near Melbourne (Australia); and Fletcher found a cubic form of graphite in a meteorite from Western Australia (Mineralog. Mag., Jan. 1887). Graphite is found both amor- phous and foliated. Coal, anthracite, peat, &C, contain from 50 to 95 p.e. of carbon. Formation.—Many attempts have been made to form diamond; none has been certainly suc- cessful (v. Liebig, Agriculturchcmic [1840] 285 ; Wilson, J. 1850. 697 ; Favre, J. 1856. 828 [from CC14]; Despretz, C. R. 37, 369 [electric current for a month from Pt to C pole] ; Simmler, P. 105, 466 [crystallisation from liquid CO..]; Lion- net, G. R. 63, 213 [from CS.,]; Chancourtois, C. C. 1866. 1037 [oxidation of hydrocarbon]; Kossi, C. R. 63, 408; Hannay, Pr. 30, 188 a. 450 [action of Mg, and Li, on gaseous hydrocar- bons mixed with N-containing compounds at very high temperatures and pressures]; Mars- den, Pr. E. 11, 20 [by dissolving amorphous C in molten Ag]). Graphite is formed:—1. By heating charcoal with molten iron, and dissolv- ing out the Fe by HC1 and HNO.Aq.—2. By the slow decomposition of HCNAq, and boiling the product with HN03Aq (Wagner, J. C. T. 1869. 230). — 3. By evaporating the mother liquors obtained in making soda; these con- tain CN compounds which are decomposed at a certain concentration of the liquid with formation of NH, and graphite (Pauli, D. P. J. 161, 129 ; Schaffner, W. J. 1869. 250).—4. By leading CO over Fe.,03 at 300°-400° (Griiner, C. R. 73, 28 ; Stingl, B. 6, 392). Amorphous C is also formed (Berthelot, C. R. 73, 494).—5. By the decomposition of CS., at high temperatures. 6. By leading CC14 over molten pig-iron (Deville, A. Ch. [3] 49, 72). Amorphous carbon is formed in many ways :—1. By heating wood, coal, or almost any animal or vegetable matter, out of contact with air, to a high temperature.—2. By the incomplete combustion of wax, tallow, oil, or other combustible compounds of C and H.—3. By decomposing, at a very high temperature and out of contact with air, the gaseous C compounds obtained in the production of gas from coal : the carbon thus obtained is very hard (v. Proper- ties). Preparation.—Pure graphite is obtained by intimately mixing 14 parts of finely powdered foliated graphite with 1 part KCIO., and 2 parts cone. H,SO„ heating on the water-bath so long as CI comes off, washing repeatedly with hot water, drying and heating to remove H,S04: if the graphite contains silica it is treated with NaF and H.,SO„ besides treatment with KC10.f and H..SO, (Brodie, T. 1860.1; v. also Winckler, J. pr. 98, 243 ; Stingl, B. 6, 391). Amorphous carbon is prepared approximately pure by strongly heating cane sugar in a closed Pt crucible, boiling the charcoal thus produced with (1) cone. HClAq, (2) KOHAq, (3) water, drying, heating to full redness in a stream of dry CI and allowing to cool in the same; H is removed as HC1, O as CO, also traces of SiO.„ Fe,Os, &c, as SiCl4, Fe.Cl,, AlaCl8, &c. The soot from semi-burnt turpentine oil, after treat- ment with ether, and heating to a high temperature in a closed vessel, is approximately pure carbon. It seems to be impossible to obtain finely divided amorphous C quite free from gases](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21995990_0001_0711.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)