Volume 1

Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors.

- Date:

- 1888-1894

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

712/796 (page 686)

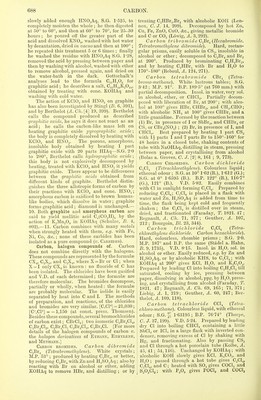

![such as H, 0, or CI; even when purified as de- scribed it retains traces of CI, this may be removed by strongly heating in connection with a Sprengel pump, but on exposure to the air considerable quantities of 0, C02, <fce. are quickly absorbed. The absorbed gases cannot be removed by heating at ordinary pressures; Erdmann a. Marchand (J. pr. 23, 159) found •2 p.c. H and -5 p.c. O in sugar-charcoal which had been heated nearly to whiteness for 3 hours. According to Porcher (C. N. 44, 203) amorphous C free from H, 0, and N is obtained by passing CC14 vapour over hot pure Na in a hard glass tube, and then heating the C obtained to a little under the temperature at which burning begins. A very hard kind of amorphous carbon is formed by placing wood (box, ash, elder, lilac, or oak), or flax, hemp, cotton, paper, or silk, in a porcelain tube, driving out all air by CS2 vapour and then gradually heating to redness for an hour (Sidot, C. R. 70, 605). The harder the wood and the higher the temperature to which it is heated, the harder and denser is the carbon produced. Various materials consisting mainly of carbon are prepared for industrial use; charcoal, by partially burning piles of wood covered with turf or earth, or by the dry distillation of wood ; coke, by heating coal in iron retorts arranged so that the liquid and gaseous products may be separated from the residual carbonaceous matter; lamp black, by partially burning tallow, turpentine, &c, and condensing the soot on cold surfaces; animal char (which however contains only about 10-20 p.c. C) by heating bones in closed vessels. Properties.—Unchanged by action of acids; has not been melted or vaporised. Diamond is a colourless, transparent, very refractive and dispersive, crystalline, solid; some diamonds are coloured yellow, brown, blue, or black. Diamond is the hardest substance known, but rather brittle; very bad conductor of electricity and heat. C.E. small, especially at low tem- peratures, at — 42° = 0. Unchanged by heating out of contact with air to 1300°-1400°; but placed between the carbon poles of a powerful battery it glows brilliantly, swells up, splits, and after cooling the surface resembles coke from bituminous coal (comp. Eose, P. 168, 497; v. Schrotter, Sitz. W. [2] 63, 462; Morren, C. R. 70, 990 ; Jacquelain, A. 64, 256 ; Gassiot, Ph. C. 1850. 893; Baumhauer, Ar. N. 8, 1). Unchanged when heated to whiteness in water- vapour (Baumhauer, I.e.). Strongly heated in a stream of O, diamond is completely burnt to C02; it may also be burnt by heating with molten KN03; or, very slowly, by powdering finely and heating with K.,Cr„0;, H,SO.„ and a little H20 (Kogers, J. pr. 50~ 411)'. Graphite occurs native both crystalline (foliated) and amorphous; it forms a grey, metal-like, hard, opaque, solid; fair conductor of electricity, especially after purification by KC103, &c. (v. supra) ; fair conductor of heat; is not changed by heating out of contact with air; burns in 0 to C02 at a high temperature, but more slowly than diamond; burnt to C02, more easily than diamond, by molten KNOs, or by K2Cr207 and H2SO,Aq ; also by heating with various metallic oxides. When graphite is heated with KC10S and HN03Aq a compound of C, H, and 0 is formed, called by Brodie graphitic acid (probably CnH405); this body is not ob- tained from diamond or amorphous carbon (v. Reactions, No. 9). The graphite-like form of coke which is formed in the upper parts of the retorts in which coal is heated for gas-making, or is obtained by passing hydrocarbon vapours through red-hot porcelain or iron tubes, is an extremely hard, metal-like, lustrous, sonorous solid ; S.G. (2-356) nearly same as that of graphite; it is a good conductor of electricity and a fair con- ductor of heat; burns with difficulty; it contains no H, and leaves only from *2 to '3 p.c. ash (Marchand a. Meyer). Amorphous carbon (sugar-charcoal; lamp- black) is a dense, black, powder ; it is ex- tremely slowly acted on by any reagents, even energetic oxidisers; non-conductor of electricity. The harder forms of amorphous carbon, obtained by calcining hard woods at high temperatures out of contact with air, somewhat resemble graphite in appearance, they are more or less lustrous, conduct electricity fairly well, and burn slowly when heated in air or 0. Ordinary amorphous C, or ordinary wood charcoal, ab- sorbs large volumes of gases: Saussure (G. A. 47, 113) gives the following volumes absorbed by 1 vol. box-charcoal at 12° and 724 mm.: NH3 90, HC1 85, SO., 65, H2S 55, N„0 40, CO., 35, CO 9-4, C2H4 35, 0 9-2, N 7-5, H 1-75. Hunter (P. M. [4] 29, 116 ; C. J. [2] 3, 285; 5, 160; 6, 186; 8, 73; 9, 76 ; 10, 649) gives these numbers for 1 volume cocoa-nut charcoal at 0° and 760 mm.: NH3 171-7, CN 107 5, NO 80-3, CH..C1 76-4, (CH.,).,0 76-2, C..H, 74-7, N20 70-5, PH3 69-1, C02 67-7, CO 212, O 17-9. According to Angus Smith (Pr. 28, 322) absorp- tion of gases by charcoal takes place in definite volumes; thus if the vol. of H absorbed under definite conditions is 1, the vol. of O = 8, CO = 6, C02 = 22, N = 4-66. Chemical reaction some- times occurs between gases absorbed by char- coal ; thus, HC1 is produced by leading H over charcoal which has absorbed CI, and S02C12 by leading S02 over charcoal under the same con- ditions. The absorbed gases are removed in vacuo. Becently heated porous wood char- coal removes many colouring matters, e.g. indigo, from solutions ; it also removes fusel oil from weak alcohol, alkaloids from aqueous solutions, many metallic salts from solutions, &c.; in some cases chemical change is pro- duced, e.g. CuS04Aq and AgN03Aq are reduced with pps. of Cu and Ag (Monde, J. pr. 67, 255 ; v. also Graham a. Hofmann, A. 83, 39 ; Graham, P. 19, 139; Weppen, A. 55, 241; 59, 354 ; Favre, A. Ch. [5] 1, 209 ; Guthe a. Harms, Ar. Ph. 69, 121; Stenhouse, A. 90, 186). Specific heat of carbon.—The follow- ing numbers summarise the chief determinations exclusive of those of Weber : the temperature- interval is about 35°-55° :— Diamond: -143 Bettendorff a. Wiillner (P. 133, 293); -147 Begnault (A. Ch. [3] 1, 202); •366 [20°-l,000°] Dewar (P. M. [4] 44, 461). Gas carbon : -165 Kopp (A. 126, 362 ; Sivpplbd. 3, 1 a. 289) ; -186 B. a. W. (I.e.); -197 B. (I.e.); -32 [20°-1,000°] D. (I.e.). Graphite: -174 Kopp (I.e.); -188 B.a.W. (I.e.); -201 B. (I.e.).](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21995990_0001_0712.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)