Volume 1

Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors.

- Date:

- 1888-1894

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

713/796 (page 687)

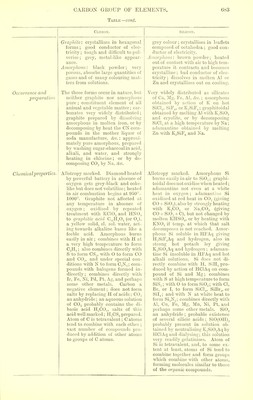

![Wood charcoal: -241 E, (I.e.). In 1874 Weber made careful determinations of the S.H. of the different forms of carbon at different temperatures; he used (1) diamond, (2) native graphite, (3) porous wood charcoal in a slender filament strongly heated in dry CI and sealed at once in a glass tube. His chief results were as follows (v. P.M. [4] 49, 161 a. 276) :— Diamond. Temp. -50° +10° 85° 250° 606° 985° S.H. -0G35 -1128 -1765 -3020 -4408 -4529 Graphite. Temp. -50° +10° 61° 201° 250° 641° 978° S.H. -1138 -1604 -199 -2966 -325 -4454 -407 Wood Charcoal. Temp. 0°-23° 0°-99° 0°-223° S.H. -1G53 -1935 -2385 These numbers show that the S.H. increases as temp, increases, but that the rate of this in- crease is much smaller at high than at low temperatures. From G00° onwards the S.H. of diamond is the same as that of graphite ; as the values for wood charcoal are nearly the same as those for graphite for the same temperature- intervals, the conclusions may fairly be drawn that at temperatures above 600° the different forms of carbon have all the same S.H., and that at lower temperatures there are two values for the S.H., one belonging to graphite and amor- phous C, the other to diamond. Allotropy of carbon. Carbon exhibits allotropic changes in a marked way ; diamond may be, superficially at any rate, changed to graphite ; amorphous C may also be changed to graphite ; each of the three varieties is charac- terised by special properties. The S.G. of each is characteristic. The heats of combustion (v. supra) are different. The S.H.s are not the same ; but Weber's results tend to show that, as regards S.H., there is but one form of C ex- isting at temperatures above 600°. Amorphous C remained unchanged when subjected to a pressure of 6,000-7,000 atmos. (Spring, A. Ch. [5] 22, 170). The three forms are clearly dis- tinguished, chemically, by their reactions with KCIO., and HNO, (v. Reactions, No. 9). A tomic weight.—Determined (1) by burn- ing diamond in O and weighing the CO.. produced (Dumas a. Stas, A. Ch. [3] 1, 5; Erdmann a. Marchand, J. pr. 23, 159 ; Eoscoe, A. Ch. [5] 26, 136 ; Friedel, Bl. [2] 41,100); (2) by heating- silver acetate and weighing the Ag (Marignac, A. 59, 287) ; (3) by heating Ag salts (oxalate and acetate) and weighing the Ag and CO., formed (Maumene, A. Ch. [3] 18, 41). The mean of all the (closely agreeing) results is 11-97 (0 = 15-96). Chemical properties.—The atom of C is tetravalent in gaseous molecules (CH4, CC1„ CBr„ &c). The atomicity of the molecule of C is unknown, as the element has not been gasi- fied ; certain considerations, e.g. the increase in S.H. as temperature increases, and perhaps the character of the spectrum, seem to indicate that the molecule of C is probably composed of several atoms. Carbon is distinctly a non-metallic element; it does not replace the H of acids to form salts; it forms stable, but easily gasified, compounds with the halogens; its oxides, and also the sulphide CSa, are distinctly acidic in their re- actions ; it exhibits allotropy in a most decided way; the spectrum of C is very complex; yet in some of the physical properties of graphite and dense amorphous carbon, this element approaches the metals (v. supra). Carbon stands at the beginning of Group IV. in the periodic classifica- tion of the elements ; the other members of this group, except Si, are more metallic than non- metallic ; C shows closer relations to Si, the first odd-series member of the group, than to any other element in the group (v. Caebon gkoup of elements). Both elements are remarkable for the great number of compounds which they form with H, O, and N. Most of the elements of Group IV., except C, form characteristic com- pounds with F, or double compounds with F and other elements. Reactions.—1. Unchanged by action of acids. 2. Heat, in absence of air, produces no change (com/p. Properties of Diamond). — 3. When strongly heated in excess of oxygen, CO., is formed : the combination is much retarded if the C and O are carefully dried (Baker, C. J. 47, 349).—4. Heated with sulphuric acid and potassium dichromatc C is slowly burnt to CO.,. j 5. Oxidised to C02 by heating with molten nitrate or chlorate of potassium.—6. Beacts with sulphur vapour at high temperatures to form CS.^.—7. Combines with hydrogen to form CJ1.,; by passing electric sparks between C poles in atmosphere of H.—8. Combines indirectly with nitrogen to form cyanogen.—9. Graphite is oxi- dised by potassium chlorate and nitric acid to graphitic acid (?CnH405 or CMH,0,.). Brodie (T. 1859. 249) heated an intimate mixture of 1 part purified and very finely divided graphite and 3 parts KC10.„ with enough very cone. HNO.,Aq to bring all into solution, at 60° for 3-4 days, until yellow vapour ceased to come off; the contents of the retort were then poured into much water; the insoluble matter was tho- roughly washed by deeantation, dried on a water-bath, and again oxidised by KC103 and HN03Aq, as before. These operations were repeated (usually 4 times) until no further change was produced, and the insoluble matter formed a clear-yellow solid. Analysis of this yellow solid, dried at 100°, gave the formula C,,H405. This body—called graphitic acid by Brodie — forms small, transparent, lustrous, yellow plates; it is slightly soluble in water; insoluble in water containing acids or salts; turns blue litmus slightly red; shaken with solutions of alkaline bases it appears to form insoluble salts, but the composition of these is very uncertain; when heated it burns explo- sively, leaving a fine, black residue ; it is easily decomposed by reducing agents such as (NH4)HS, SnCL, HIAq, &C. (v. infra). Brodie supposed this body to be a compound of a hypothetical element which he called graphon, and to which he gave the atomic weight 33 ; he formulated graphitic acid as Gr4H403, and regarded it as the carbon analogue of a silicic acid Si4H405 obtained by Wohler from graphitoidal silicon. Gottschalk (J.pr. 95, 321) placed a very intimate mixture of 1 part (oOgrms.) purified, very finely divided graphite with 3 parts KC103 in a large flask surrounded by ice-cold water, and very](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21995990_0001_0713.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)