Volume 1

Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors.

- Date:

- 1888-1894

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

759/796 (page 733)

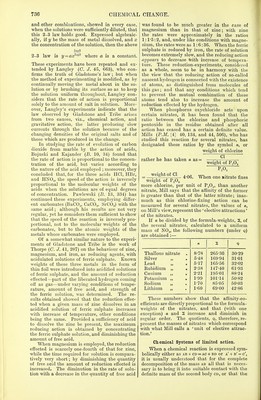

![ammonia is formed; with the moist gases, how- ever, a trace of NH3 is obtained. Alloteopic Change. Several of the elementary bodies are known to exist in two or more different modifications, such for instance as sulphur, selenion, carbon, phosphorus, and oxygen : the several forms of each element exhibit more or less strongly marked differences in chemical as well as physical properties. It is probable that such different modifications of one elementary body consist, as in the case of oxygen and ozone, of different atomic groupings or aggregates of atoms. The means by which the change from one modifica- tion of an element to another is brought about are various. Oxygen is converted into ozone by the elee'rie spark or 'silent discharge,' and ozone is changed again into oxygen by heat; yellow phosphorus is converted into the red modification either by light or by heat, and the red modifica- tion is again reconverted into yellow phosphorus at a higher temperature; sulphur and selenion undergo several changes under the influence of heat; in the case of carbon, the conditions ne- cessary to bring about metamorphoses are not fully known. The study of certain isomeric compound bodies (v. Isomeeism) has shown that the transformation of one isomeride into another is, in some cases, somewhat analogous to the phenomena of dissociation. If solid para- cyanogen (CN)n is heated in a closed vessel to 860° it is entirely converted into cyanogen gas (CN)2; the pressure increases until the gas con- denses and is liquefied on the cooler parts of the apparatus. At temperatures below 500° little or no decomposition occurs. As the para- cyanogen is heated above this temperature a slow transformation takes place into gaseous tyanogen, and the transformation continues until the pressure of the cyanogen gas attains a certain definite limit beyond which it does not rise, and there is no further evolution of gas. Exhausting the apparatus and maintaining the temperature, the pressure again rises to its previous limit and remains stationary however long the heating is continued. For every such temperature there is a maximum pressure reached which limits the further decomposition of the paracyanogen into gaseous cyanogen. If now when the pressure has attained its limit, at a given temperature, a quantity of cyanogen gas is forced into the apparatus, the pressure slowly falls to the initial limit with the trans- formation of gaseous cyanogen into solid para- cyanogen. Troost a. Hautefeuille {C. B. 66, 735, 795) have found the following values for these pressures of transformation at different tern- peratures:— Temp. Pressure of transformation. 502° 54° mm. 506 56 „ 559 123 „ 575 129 „ 587 157 „ 599 275 „ 601 318 ,, 629 868 „ 640 1310 „ The transformation of solid paracyanogen into gaseous cyanogen is seen to be analogous to the volatilisation of a liquid in presence of its own vapour; but the formation of red phos- phorus from the yellow material or vice-versd is a more complex process. If a quantity of yellow phosphorus is heated in a closed vessel (say to 500°), the mass of phosphorus being more than sufficient to volatilise in the space, a maxi- mum pressure is quickly attained. After a time the pressure gradually falls, more or less quickly according to the temperature, till it reaches a minimum at which it remains constant. Pro- vided there is no change of temperature, the vapour of the phosphorus is gradually converted into the red modification which condenses on the sides of the apparatus. If the quantity of phos- phorus introduced into the apparatus is just sufficient to volatilise and fill the vessel with vapour at the first pressure (the heating being continued), red phosphorus begins to form after a time, and the pressure continues to fall until the minimum limit is reached as before. If, however, only sufficient ordinary phosphorus is used to fill the apparatus with vapour at the lower limit of pressure, no red phosphorus is formed, however long the heating may be con- tinued. These two pressures—the maximum is first attained, and the final minimum limiting the transformation of yellow into red phos- phorus—depend solely upon the temperature. Troost and Hautefeuille (A. Ch. [5] 2,153) found the following numbers relating to these pheno- mena : Temp. Pressure of vapour of Maximum pressure p limiting the trans- of p vapour first formation produced 360° •12 atms. 3-2 atms. 440 1-75 „ 7-5 „ 487 6-80 „ 494 18 503 21-9 „ 510 10-8 511 26-2 „ 531 16 „ 550 31 „ 577 56 The rates at which the transformation takes place as well as other phenomena exhibited during the change have been studied by Lemoine (A. Ch. [4] 24, 194). He gives the following numbers illustrative of the progress of the change in time: Quantities of ordinary P remaining at Grams. 5 mins. fh. 2h. 8h. 17h. 24h. 32h. ilh. 2-9 2.9 5-9 5-3 4-9 4-7 16-0 5-0 24-0(Hittorf) 15-5 11-1 7-0 4-4 30-5 5-4 4-0 3-7 3-6 Lemoine (C. B. 73, 990) has given a mathe- matical theory of the changes that red or yellow phosphorus undergoes when heated in a closed vessel, and has compared his formulas with the results of experiment. Let p be the total mass](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21995990_0001_0759.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)