Volume 1

Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors.

- Date:

- 1888-1894

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

770/796 (page 744)

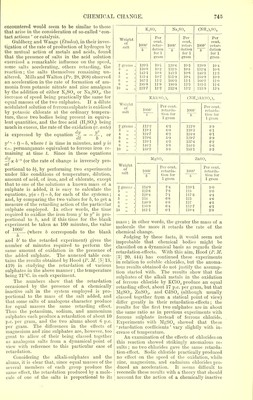

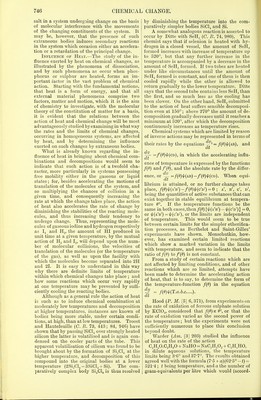

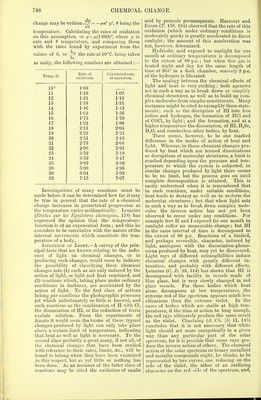

![a maximum, then diminished to a minimum, and again increased on addition of more H2C./!04. Experiments on the relation between the time of continuance of the action and its amount showed that after a certain interval the course of the change was represented by an hyperbola. The reason of this regularity only occurring after the action had proceeded some time was traced to the double changes that take place, first between the MnSO,, and K,Mn2Ob, and then between the Mn02 produced and the C2H,04. Both changes are, however, comparatively slow ; but if either of them occurred very rapidly compared with the other, in presence of equivalent quantities of materials, the whole course of the change would doubtless be represented by an hyperbola. Hood (P. M. [5] 6, 371; 8, 121) has studied the rate of oxidation of ferrous sulphate by potassic chlorate, and the influence exerted on the process by variations (i) in the amounts of acid used and (ii) in the temperature. The equation for equivalents being 6FeS04 + KC103 + 3H.,S04 = 3Fe2(S04)3 + KC1 + 3H.,0, it is evident that the rate of change will be the product of three factors. The acid being in large excess and KC103:6FeS04 = y;l, the rate of change by equa- tion (3) is = — i*By(v — 1) a + y where b equals at the amount of acid; or log, % — (n-l)k + y /ub(w-1)a(c-<) ; if,however,KC103:6FeS04=l:l, then ^ = — jubw2, or y(a+t) = -^—. By a series at p.B of determinations of y (c.c. of permanganate) at indefinite intervals of time, the constants in either of these equations (,ub and c, and ,ub and «) were found for different conditions of tempera- ture, amount of acid (b), &c, and consequently a measure was obtained of the changes produced in the rate of oxidation by -such variations. Hood found that for this reaction both these formulae hold good, and, as theory indicates, the rate of oxidation, within certain limits, is pro- portional to the amount of free acid; as the amount of acid, however, becomes comparatively very great the oxidation progresses much more rapidly than the acid increases. When HC1 replaces H2S04, in order to produce the same rate of oxidation the amounts must be as 365 : 80. Ostwald (J. pr. 27, 1) has studied the interest- ing reaction B.CONH, + H20 = B.CO.ONH, with reference to the accelerating influence acids have upon the rate of the change. This reaction is a striking instance of so called ' predisposing' affinity, the reaction being a very slow one when water alone is employed. (For details of this in- vestigation, v. the article Affinity, p. 79.) The decomposition of the ethereal salts, e.g. methylic acetate, by water, affords an example of chemical change somewhat analogous to that of the acetamides. The difference between the two cases is that in the former the water resolves the compound into two others, alcohol and acid, whereas in the latter the water is assimilated to form a more complex compound. The presence of acids greatly accelerates the decomposition of the ethereal salts, as is the case with the acet- amides ; the relations between speed of action and quality of acid have been investigated by Ostwald (J.pr. 28, 449), v. Affinity. Betaedation and Accelebation of Chemical Changes.—In the reaction that takes place when an alcohol and an organic acid are mixed, the amount of change is limited by the inverse action that arises between the products of the change, ethereal salt and water, which inverse action tends to the re-formation of the original alcohol and acid; it is consequently evident that the rate at which the etherification progresses is re- tarded by this inverse action. In like manner if BaS04 is acted on by K2C03, the rate of the de- composition is retarded by the inverse action that occurs between the BaC03 and K;S04 which results in the formation of the original bodies. The same may be said as regards the rate of all those reactions which are limited in extent by inverse chemical changes. There is, however, another kind of retarda- tion possible, not arising from any secondary chemical changes taking place in the system, but of a purely physical origin. If in a homogeneous system undergoing change, such for instance as is represented by the equation a + b = ab, the chemically active bodies be considered to be in a state of continual motion, the rate of formation of ab will be proportional to the number of im- pacts between the a's and b's in a unit of time. It is conceivable then that if the molecules ab are not removed from the sphere of action their mere presence will hamper the movements of the remaining a's and b's, and by so doing will diminish the number of impacts between them in a unit of time, that is to say, will retard their rate of combination. That retardation of a chemical change does arise by the addition of a quantity of one of the products has been shown to be true in several instances ; but whether the effects are to be interpreted on a physical basis, as is done here, or on a chemical basis, cannot be decided with certainty until much more ex- perimental evidence has been obtained. The study of the influence of chemically inactive bodies on systems undergoing change, that is to say of bodies which probably do not take part chemically in the reactions, forms a wide field for research ; and there is no doubt that the re- sults obtained will have an important bearing on chemical science considered in its dynamical aspect. An acceleration in the rate of a chemical change may be brought about by an increase in the amount of any one of the active constituents of the system; such an acceleration, as has been already shown, is easily explained by the law of mass-action, viz. that the total mass of each constituent takes part in the reaction. There are instances, however, somewhat more difficult of explanation, such as the inversion of cane sugar, or the decomposition of methylic acetate, by acids, wherein the addition of an acid merely accelerates the change, the mass of the acid remaining the same at the finish as at the beginning of the reaction. The tendency to undergo change in these instances is merely increased by the presence of the acid, and this tendency, measured by the speed of the change, is dependent on the character of the acid em- ployed (v. Ostwald's experiments detailed in Affinity, p. 79). The difficulties that are here](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21995990_0001_0770.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)