Volume 1

Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors.

- Date:

- 1888-1894

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Watts' dictionary of chemistry / revised and entirely rewritten by H. Forster Morley and M.M. Pattison Muir ; assisted by eminent contributors. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

772/796 (page 746)

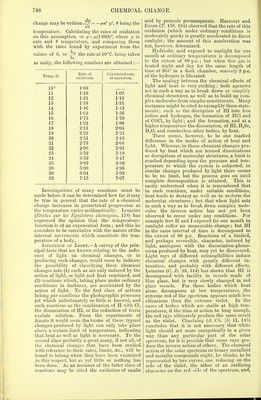

![salt in a system undergoing change on the basis of molecular interference with the movements of the changing constituents of the system. It may be, however, that the presence of such extraneous bodies induces secondary reactions in the system which occasion either an accelera- tion or a retardation of the principal change. Influence op Heat.—The study of the in- fluence exerted by heat on chemical changes, as illustrated by the phenomena of dissociation, and by such phenomena as occur when phos- phorus or sulphur are heated, forms an im- portant factor in the vast problem of chemical action. Starting with the fundamental notions, that heat is a form of energy, and that all external material phenomena comprise two factors, matter and motion, which it is the aim of chemistry to investigate, with the molecular theory of the constitution of matter for a basis, it is evident that the relations between the action of heat and chemical change will be most advantageously studied by examining in what way the rates and the limits of chemical changes, occurring in homogeneous systems, are affected by heat, and by determining the influence exerted on such changes by extraneous bodies. What is already known regarding the in- fluence of heat in bringing about chemical com- binations and decompositions would seem to indicate that such action is of a twofold cha- racter, more particularly in systems possessing free mobility either in the gaseous or liquid states; for, besides accelerating the motions of translation of the molecules of the system, and so multiplying the chances of collision in a given time, and consequently increasing the rate at which the change takes place, the action of heat also accelerates the rate of change by diminishing the stabilities of the reacting mole- cules, and thus increasing their tendency to undergo change. Thus, representing the mole- cules of gaseous iodine and hydrogen respectively as I2 and H2, the amount of HI produced in unit time at a given temperature, by the mutual action of H2 and I21 will depend upon the num- ber of molecular collisions, the velocities of translation of the molecules (or the temperature of the gas), as well as upon the facility with which the molecules become separated into 2H and 21. It is easy to understand in this way why there are definite limits of temperature within which chemical changes take place ; and how some reactions which occur very rapidly at one temperature may be prevented by suffi- ciently cooling the reacting bodies. Although as a general rule the action of heat is such as to induce chemical combination at moderately low temperatures and decomposition at higher temperatures, instances are known of bodies being more stable, under certain condi- tions, at high, than at low temperatures. Troost and Hautefeuille (C. B. 73, 443; 84, 946) have shown that by passing SiCl, over strongly heated silicon the latter is volatilised and is again con- densed on the cooler parts of the tube. This apparent volatilisation of silicon was found to be brought about by the formation of Si,Clu at the higher temperature, and decomposition of this compound into the original bodies at a lower temperature (2Si2Cls = 3SiCl4 + Si). The com- paratively complex body SiaCla is thus resolved by diminishing the temperature into the com- paratively simpler bodies SiClj and Si. A somewhat analogous reaction is asserted to occur by Ditte with SeH2 (C. B. 74, 980). This chemist says that if selenion is heated with hy- drogen in a closed vessel, the amount of SeH2 formed increases with increase of temperature up to 520°, but that any further increase in the temperature is accompanied by a decrease in the amount of SeH, formed. If two tubes are heated under like circumstances until the amount of SeH2 formed is constant, and one of them is then cooled rapidly while the other is allowed to return gradually to the lower temperature, Ditte says that the second tube contains less SeH, than the first, and so much less as the cooling has been slower. On the other hand, SeH, submitted to the action of heat suffers sensible decomposi- tion even at 150°; above 270° the amount of de- composition gradually decreases until it reaches a minimum at 520°, after which the decomposition continuously increases as temperature rises. Chemical systems which are limited by reason of inverse actions may be represented in terms of their rates by the equations = /(O)iJ'(ab), and ~- =f(d)\f/(cv), in which the accelerating influ- ence of temperature is expressed by the functions f(6) and/'(0), and the absolute rate by the differ- ence, or ^ = /(0)i|<(ab) — f(6)ty(cD). When equi- librium is attained, or no further change takes place, /(0)<Ha'b') -/(fl)^(o'D') = 0 ; a', b', c', d', being the quantities of active substances that can exist together in stable equilibrium at tempera- ture 8°. If the temperature functions be the same in both cases,then/(0) JiI'(a'b') — i|/(c'd')} =0, or ^(a'b') =i|/(c'd'), or the limits are independent of temperature. This would seem to be true between certain limits for the simpler etherifica- tion processes, as Berthelot and Saint-Gilles' experiments have shown. Menschutkin, how- ever, has examined certain limited reactions which show a marked variation in the limits with temperature, and seem to indicate that the ratio of f(0) to f(B) is not constant. From a study of certain reactions which are not affected by limiting conditions, and of other reactions which are so limited, attempts have been made to determine the accelerating action of heat, that is to say, to determine the form of the temperature-function f(8) in the equation || = f(e^(T.a.b.c....). Hood (P. M. [5] 6, 371), from experiments on the rate of oxidation of ferrous sulphate solution by KC103, considered that f(8)cc 6-, or that the rate of oxidation varied as the second power of the temperature; but the experiments were not sufficiently numerous to place this conclusion beyond doubt. Warder (Am. [3] 203) studied the influence of heat on the rate of the action C2H5O.C,H30 + NaHO = NaC.,H,0, + C„H5HO, in dilute aqueous solutions, the temperature limits being 3'6° and37'7°. The results obtained agreed well with the formula (7-5 + a) (62-5° — t) = 521-4 ; t being temperature, and a the number of gram-equivalents per litre which would (accord-](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21995990_0001_0772.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)