Improvement to Palmer's endless self-computing scale and key : adapting it to the different professions, with examples and illustrations for each profession, and also to colleges, academies and schools : with a time telegraph making, by uniting the two, a computing telegraph / by John E. Fuller.

- Fuller, John E. (John Emery), 1799-1878

- Date:

- 1851

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Improvement to Palmer's endless self-computing scale and key : adapting it to the different professions, with examples and illustrations for each profession, and also to colleges, academies and schools : with a time telegraph making, by uniting the two, a computing telegraph / by John E. Fuller. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the National Library of Medicine (U.S.), through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the National Library of Medicine (U.S.)

2/16

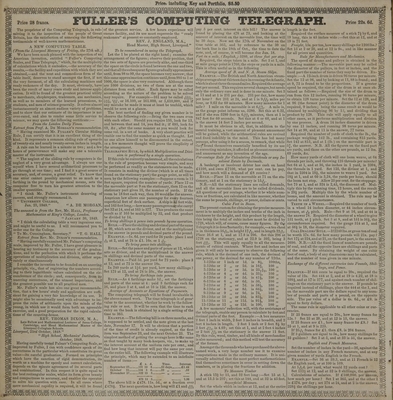

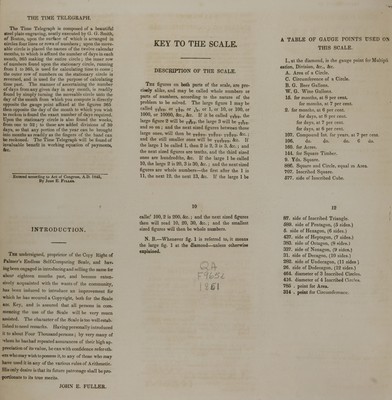

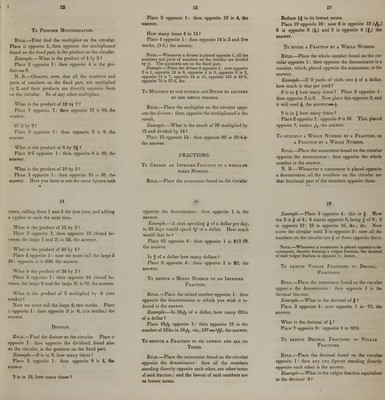

![Price? including Key and Portfolio, $6.60 mmwg?m&&:&& Price 28 francs. FULLERS COMPUTING TELEGRAPH. Price 22s. 6d. Jfq The proprietor of the Computing Telegraph, in sub- mitting it to the inspection of the people of Great Britain, has the satisfaction of annexing the following testimonials of well-known mathematicians. A NEW COMPUTING TABLE. (From the Liverpool .1/' ».</, the 2~th ult.J ', We have boon much pleased with the inspection of an | American invention, entitled Fuller's Computing and Time Telegraph, which, for the multiplicity of calculations which it embodies,—the accuracy of the > results,—the facility and expedition with which they are ! obtained,—and the neat and commodious form of the ! table itself, deserves to stand amongst the first, if not \ the very foremost, of all the calculating machines and ; ready reckoners of the day. It must, obviously, have > been the result of many years study and intense appli- f cation. It will be found of the greatest practical utility i to merchants, shopkeepers, tradesmen, ano mechanics, I as well as to members of the learned proicssions, to J students, and men of science generally. It solves almost ' instantaneously an almost endless variety of problems, > and to show that our estimate of its importance is not ' over-rated, and also to render some little service to . we may quote the following certificate :— From the London Daily Times. J Extract from Prof. A. De Morgan's recomim | Having examined Mr. Fuller's Circular Sliding | Rule, I can certify that it is an excellent thing of the i kind. It represents a common sliding rule of upwards ! of twenty-six and nearly twenty-seven inches in length. I A rule can be learned in a minute or two ; and a lew | hours of perseverance will make any one a tolerable [ master of the instrument. i The neglect of the sliding rule by computers is the '• neglect of a very great advantage. I always use one ! myself when I have several arithmetical processes to I go through at one time; and I find it a great source of | accuracy, and, of course, a great relief. To know that 1 one error cannot possibly amount to so much as a - farthing in the pound by mechanical means, sets the i computer free to turn his greatest attention to the I smaller quantities. J I think Mr. Fuller's instrument deserving of J success, and strongly recommend it. > University College, Jan. 23, 1849. A. DE MORGAN. ' The annexed is from the Rev. Mr. Hall, Professor of Mulhemutics at King's College, London. January 30, 1849. i I think the calculating table a very ingenious one, I and might be useful to us. I will recommend you to i order one for the College. J To Mr. Cunningham, Secretary. T. G. HALL. J Extract from Rev. Mr. Dixon's recommendation. i Having carefully examined Mr. Palmer's computing 5 scale, improved by Mr. Fuller, I have great pleasure in , bearing my testimony to the accuracy of the gradua- J tions, and to the perfection with which it performs the ? operations of multiplication and division, either sepa- ' rately or simultaneously • I consider the invention to be founded on an unerring ? principle, viz., that of registering the numbers accord- i ing to their logarithmic values calculated on the cir- J cumference of the circle; and, consequently, from its J unerring correctness, of the utmost importance, and t the greatest possible use to all practical men. , Mr. Poller's scale has also one great recommenda- [ tion, that a few hours' study and application are suffi- [ cient for gaining a very fair knowledge of its use. It | might also be occasionally used with advantage to im- [ press the rules of arithmetic upon the minds of the i young, in which use it would form both an agreeable i exercise, and a good preparation for the rapid calcula- ' tions of the counting-house. I REV. THOMAS DIXON, M. A., Late Fellow and Mathematical Lecturer of Jesus College, Cambridge, and Head Mathematical Master of the Liverpool Collegiate Schools. ! Liverpool, 23rd October, 1848. j High School, Mechanics' Institution, October, 1848. i Having carefully tested Palmer's Computing Scale, as ! improved by Fuller, I can with confidence speak of its ', correctness in the particular which constitutes its great ; value—its careful graduation. Formed on principles which have the sanction of rigid demonstration, its | worth as a machine for speedy and correct calculation, depends on the minute agreement of its several parts ! and combinations. In this respect it is quite equal to ; the best rectangular scales, whilst its form irives beauty | and compactness to accuracy, and enables the operator | to solve his question with ease. In all cases where ■ mere mechanical rapidity is required, it will be found of the greatest service. A few hours experience will ensure facility, and its use must supersede the ready reakoners at present so constantly employed. REV. J. ENGLAND, M.A., Head Master, High Street, Liverpool. To be remembered in using the Telegraph. Let the 1 be placed at the right hand ; examine the arrangement of the figures ; observe their position, that the two sets of figures are precisely alike, and one-third the space on the circle is found between the one and two, and that all the suhseq uent figures gradually approximate until, from 98 to 99, the space becomes very narrow; that this same approximation continues until,from 995 to 1 or 1000, the space is also very contracted. Although there are 1000 divisions, no two of them are at the same distance from each other. Each figure may be called according as the nature of the problem to be solved may require. For example—161 may be called TVV~r> , or 16.100, or 161.000, or 1,610,000, and if any mistake be made it must at least be tenfold, which would be seen at a glance. The best method of finding any given number is to observe the following rule ;—Bring the two ones even with each other. Should you require 135, look for 13, and between that and 14, you find it; if 695, look for 69, dtc , after the same manner as you would look for some vol. in a set of books. A very short practice will enable one to find the number as quick as thought. Let no one allow himself to be disconcerted in the outset, as a few moments thought will prove the simplicity of the arrangement. Telegraphic Rule, by which Multiplication and Divi- sion is performed by a single operation. If this rule be correctly understood, all thecalculations in the rule of proportion become very simple, and may be performed as readily as the statements can be made. It consists in making the divisor (which is at all times found on the stationary part) the gauge point, as will be seen by the following examples;—Suppose a room is 12 feet square, required the number of yards. Place 12 on the moveable part at 9 on the stationary, then 12 on the stationary part gives 16, the number of yards. If the room be 18 feet each way, then 36 would be the answer. American law allows one passenger for every fourteen superficial feet of deck surface. A ship is 32 feet wide, and 165 fectlong,—howmany passengersmay she carry? Set 32 at 14, and at 165 is 377. This produces the same result as if 165 be multiplied by 32, and that product be divided by 14. To bring shiUinga .V pence into pounds hy one operation. Rule.—Place the shilling and decimal part of thesame at 20, which acts as the divisor, and at the multiplicand is the answer in pounds and decimal parts of the pound. EXAMPLE.—Is. 6d. per yard for 24 yards : place 1 and Ts„ at 2, and at 24 is £1. 16s. or 1 JU To bring pence into shillings. Rule.—Set the pence and parts of pence at 12, which acts as divisor, and at the multiplicand is the answer in shillings and decimal parts of the same. EXAMPLE.—Paid 3d. per yard for 72 yards: place 3 at 12, and at 72 is the answer 18s. In 240 yards at ljd. per yard, how many shillings ? Set 175 at 12, and at 21 is 35s., the answer. To bring farthings into pence. Rule.—As 4 farthings make Id., set the farthings and parts of the same at 4 : paid 3 farthings each for 16, and place 3 at 4, and at 16 is 12d. the answer. Average of Accounts or Equations of Payments. The computing telegraph will be found invaluable in the above-named work. The time telegraph is of grea^ value to the accountant, whether he work by the follow- ing rule or not. It will be seen that the time to each entry on the book is obtained by a single setting of the time to 365. Exa mple.—The following bill is on three months, and is supposed to be settled, and the note given at the last date, November 17. It will be obvious that a portion of the time of credit is already expired, as the first item was September 23, and the next October 25. The simplest method of getting the average here is the same as that taught by many book-keepers, viz., to make up the interest account at the uniform rate per cent., and find how long that interest will pay the same per cent, on the entire bill. The following example will illustrate ihe principle, which may be extended to an indefinite number of items:— £ s. d. Time. Interest. September 23 191 10 8 55 days £1.44 478 II 5 1.96 The above bill is £478. lis. 5d., or a fraction over £478 J. The next question is, how long will £1 and ^-t pay 5 per cent, interest on this bill ? The answer is found by placing the 478 at 73, and looking at the amount of interest on the moveable line, the time will be 30 days. Now set the 17th of November on the time table at 365, and by reference to the 30 on the back line is the 18th of Oct., the time to date the note, and, of course, it will become due Jan. 18. Feet in a mile, (English,) 5280, at three feet per step. Required, the steps taken in a mile. Set 3 at 1, and at mile gauge point is 1760, the Steps or yards in a mile. This is often useful as in the following Average speed of B. am! X. A. steam Ships. Example.—The British and North American steam- ships average about thirteen days in crossing theAtlantic, which is about three thousandmiles. Required the average feet per second. This requires several changes,but needs only the ordinary care and is done in one minute. Set 3 at i3 and at 1 is 231 per day. 231 per day, how many per hour? Set 231 at 24, and at 1 is 9^Uj miles per hour, or 9.62 for 60 minutes. How many minutes for 1 mile ? 1 mile on the moveable is at 0T'(h*7. A mile is, as the gauge point informs us, 5280. Set this at 6.22, and if she run 5280 feet in 6T2S2^ minutes, then at 1 is 847 feet for 60 seconds. Set this at 6 or 60, and at 1 is the answer 14 feet 2 inches per second. It must be obvious to all, that, in addition to the mental training, a vast amount of pleasant amusement will be gained, while the arithmetical rules are revived and fixed indelibly in the mind. This has led many persons, after using it for a season, to remark, that while they* found themselves essentially benefited by its use in correcting mistakes, it afforded as pleasant recreation and amusement as any invention of the age. Per-centage Hale for Calculating Dividends or any In- .' Estate by Decimals. A bankrupt or insolvent debtor has cash on hand £1100, and owes £7100, what per cent, can he pay, and how much will a demand of £8 receive ? Rule.—Place 11 on the moveable at 71 on the sta- tionary, and at 1 on the stationary is 15^. N.B.—All the stationary lines are called demands, and all the moveable lines are to be called dividends. All questions of per centage, whether it be whole num- bers or fractions, arc calculated in like manner,whether the sums be pounds, shillings, or pence, dollars or cents. Cubic Feet in Boxes. The present custom for obtaining the precise measure- ment is to multiply the inches and tenths of the inch in thickness by the height, and this product by the length, this being the total of cubic inches must be divided by 17-S, which will, of course, cause many figures. By thp Telegraph it is donelnstantly; for example,—a tea chest is in thickness 16^, in height 17A-, and in length 22T;7. Place 16.6 at 1, and at 17.8 is 296. Set this 296 at 1728 on the stationary, and at 22.9 is 392, being 3 feet T-'-2lT. This will apply equally to all the measure- ments of cubical contents. Where feet and inches are given it will only be necessary to observe the following rule, which is the decimal of one inch, the decimal of one penny, or the decimal for any number of 12ths. l-12thsor 1 inch or Id. is 81, lOOths, 2-12ths or 2 „ or 2d. is 16 j, 100 „ 3-12ths or 3 „ or 3d. is 25TJj, 100 „ 4-12ths or 4 „ or Id. is 33J, 100 „ 5-12ths or 5 „ or 5d. is 41 j, 100,, 6-12ths or 6 „ or 6d. is 50, 100 „ 7-12ths or 7 „ or 7d. is 58J, 100 „ 8-12ths or 8 „ or 8d. is 66J, 100 „ 9-12ths or 9 „ or 9d. is 75, 100 „ 10-12ths or 10 „ or lOd. is 831, 100 „ ll-l2thsor 11 „ or lid. is 91J, 100 „ 12-12ths or 12 „ or 12d. is 100, 100 „ A few moments' reflection will, with the assistance of the telegraph, enable any person to calculate by feet and decimal parts of the foot. Example :—A box measures 2 feet 1 inch in width, 2 feet 3 inches in breadth, and 2 feet 4 inches in length. 2 feet 1 inch or 2 feet 8^ by 2 feet -j2,*;?, is 4.69; set this at 1, and at 2 feet 4 inches or 2 feet A^ on the stationary is the answer 11 feet. By this rule, wood, timber, and all kinds of merchandise is also measured; and this method will test the accuracy of the former. Amongst the thousands who have purchased the above- named work, a very large number use it to examine computations made in the ordinary manner. It is unj versally admitted that the most perfect mathematicians find themselves sometimes in error in setting down the numbers, or in placing the fractions for addition. To Measure Timber A stick 134 by 15, and 32 feet long :—Set 15 at 1, and at 13.5 is 202 ; set this at 114, and at 32 is 45 feet. Supet ft Set the whole width in inches at 12, and at the entire length is the feet. $Q Required the surface measure of a stick 7J by 6, and v.-* 19 long, this is 45 inches wide:—Set this at 12, and at A 19 is 71 feet. 1(8 Freight, 15s. per ton, how many shillings for 1200 lb- Set 15 at 2 or 20, and at 12 is 9s., and in like mamin for all prices and quantities. v™ Pule for Man \d Mechanics. The speed of drums and pulleys is obtained in the following manner:—The moveable part ma] I the diameter of the pulleys, in feet or inches, and the .('--^ fixed part the number of turns they maybe driven. Ex- 7^ ample:—A 12-inch drum is driven 96 turns per minute. - Set the 12 at 96, and by looking at 11, 88 is found ; and (O at 9, 72 is found to be the proportions. If a greater ■. - speed be required, the size of the drum is at once ob- $ci tained as follows :—Required the size of the drum to !/z/S run from this 12 inches, running 96 turn- per minute, , J to obtain 128 turns per minute. Set the 12 at 128, and :(0 at 96 (the former point) is the diameter of the drum required, 9 inches; being the same n.-ult as would be '^ , obtained by multiplying 96 by 12, and dividing that 7,~sJ product by 128. This rule will apply equally to all i other cases, as it performs multiplication and division jEJ> by one process. A drum 14 inches diameter is driven ME? by one 11 inches, and running 98 turns per minutt Set 14 at 98, and at 11 is the answer, 77 turns '^r<, Required the number of yards of cloth to the lb., tip package weighing 142 lb., and containing 815 yards. ;jO Set 142 at 815, and at 1 (lb.) on the moveable part is v„; the answer. N.B. All the figures on the fixed part . arc yards, and those on the other are pounds, as 12 lbs. 5fcJ 69 yards, &c. ' How many yards of cloth will one loom weave, at 64 A1-^ threads per inch, and throwing 126 threads per minute? V/~? Set 64 at 1, and at 36, the inches in 1 yard, is 2304, <^T} the threads in 1 yard. Set 125, the divisor at 1, and jfl3 that in 2304is 18J, the minutes to weave 1 yard. Set «J§ 18J at 1, and at 60 is 3,24, the yards per hour, should gQ the loom not stop. Allow 25 per cent, for the stoppage. Vg Set 75 at 1, and at 324 is 2,43, the discount off. Mul- <*g tiply this by the running time, 12 hours, and the result <fc> is 29J yards. Multiply this by the whole number of c/^y looms, and the amount is obtained. The rule may be 3t-S varied to suit circumstances. *(c> Teeth in a Wheel.—Required the number of teeth | j in a wheel 14 inches diameter, or 44 inches circum- *fe> fcrencc, at Jg pitch. Rule—Set 9 at 16, and at 44 is <jco the answer 78. Required the diameter of a wheel to give 8f^ 151 teeth, at j> pitch. Set 3 at 8, and at 151 is 561, the ;/g circumference required. Set the gauge 314 at 1, and at 56J is 18, the diameter required. ;{0 CoalDealers'Rule.—If 2240 lbs.or gross tonofcoal ftf^ be worth 17s. 6d. for how many pounds will 21s. pay ? tXT^v Set 17{ at 224, and at 21, on the fixed part, is the answer, MR 2690. N.B.—All the fixed lines of numbers are pounds ;X^ 6f coal, and all the opposite lines are shillings and pan of the same. By obtaining the weight of one cubic foot of coal, a body of any' dimension- maybe calculated, v and the number of tons given in one minute. SffiFs Exchange of the different currencies into Pounds, Slii: lings, and Pence. Example—If 444 cents be equal to 20s., required thi value of 19s. Set 444 at 2, and at 19 is 4.22, at 18 is jyy 399}, and at 17 is 377, and against each number of shil- lings on the stationary part is the answer. If pounds be *grs required instead of shillings, place the 444 at the 1, ami . on the moveable part are the dollars equal to any num- ;vO ber of pounds and parts of a pound, on the opposii side. The par value of a dollar is 4s. 6d., or £9. is <V-:> equal to forty dollars. HC> The same rule is applicable to all other coins or cur- \, , rencies. ;'0 If 25 francs are equal to 20s., how many francs for JR 12s. ? Set 25 at 20, and at 12 is 15, the answer. Xfi If 25 francs are £1., how many francs for £9. ? Set '^Z> 25 at 1, and at 9 is 225. e, > If 25-ft francs for £1. then £8. is 204 francs. $8 If 3 guilders are equal to 5s., how many shillings for 'Jr< 33 guilders ? Set 3 at 5, and at 33 is 55, the answer. £-i English and French Measures. Jv3 Set the number of inches in the yard—36, against the '{£> number of inches in any French measure, and at any ft) given number of yards English is the French. Example.—Set 36 at 39.3, and at 11 French is 12 Vg the English yard, or at 100 is 109. At l-ffi. per yard, what would 32 yards cost ? (O Set 112^ at 12, and at 32 is 3 shillings, the answi , Calculations of salaries. If £100.0110. per annum, ^ how much per hour ? Set 1 at 305, and at the other 1 ftg is £274. per day ; set 274 at 24, and at 2 is the answ. 228J the shillings per hour](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21121175_0002.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)