Volume 1

Chambers's Information for the people / edited by William and Robert Chambers.

- Date:

- 1848-1849

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Chambers's Information for the people / edited by William and Robert Chambers. Source: Wellcome Collection.

33/824 page 23

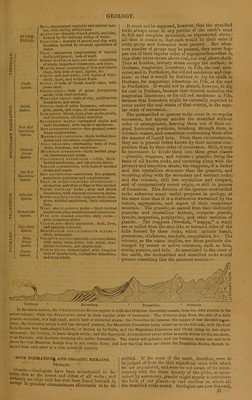

![of animal remains. We are tlius tempted to surmise that the formation of the limestone beds of the inferior stratified series, marks some early and obscure stage of organic existence on the surface of our planet. No distinct remains of plants or animals have, indeed, been found in the series; and it is customary to point to tho next upper series, in which both do occur, as the dawn of organic life. Yet many geologists are of opi- nion that the inferior stratified rocks might have con- tained such remains, though the heat under which the rocks seem to havo been formed may have obliterated every trace of such substances. The inferior stratified series constitutes in most regions the great depository of the metals—gold, silver, tin, copper, &c.—which occur in irregularly-intersecting veins, composed of ore- stone differing in composition from that of the contain- ing strata. For opinions as to the origin and character of veins, we must refer to the sheet • “ Metals and Metallurgy.” transition. Grauioacke and Silurian.—All the rocks hitherto de- scribed are of crystalline texture, and, apparently, che- mical phenomena have attended their formation. In the group we have now arrived at, traces of mechanical origin and deposition become apparent; but still a few strata resembling the preceding occur throughout the lower parts of this series, as if the circumstances under which the earlier rocks were formed had not entirely ceased. Hence the term transition, as implying a pass- ing from one state of things to another. The rocks forming the lower part of this group, and which are sometimes separately classed as the Lowest Fossiliferous Group, are an alternation of beds of chlo- rite, talcose, and other slates, resembling those of the inferior stratified series, with beds of clayey and sandy rock, of apparently mechanical origin, and thin beds of limestone in which a few fossils are found. It thus appears that the cessation of the chemical origin of rocks, and the commencement of organic life, are events nearly connected; and it has thence been sur- mised that the temperature of the earth’s surface was now for the first time suitable to the production and maintenance of organic things. At the same time, the alternation of the rocks teaches us the instructive fact that the change was not direct or uniform, but that for some time the two conditions of the surface super- seded each other. This is conformable with a general observation, which has been made by Sir H. de la Beche—namely, that however sudden changes may have taken place in particular situations, a general change of circumstances attending rock formations is usually seen to have been more or less gradual. The few fossils found in this part of the series—the Grau- wacke proper—are, as far as ascertained, the same, or nearly so, as those of the superincumbent Silurian. The Silurian group—so called from its being very clearly developed in that district of country between England and Wales which was inhabited by the ancient iSilures consists of arenaceous and slaty rocks, of evidently mechanical origin, intermixed with nume- rous beds of limestone and calcareous shales. The general composition of the series indicates its hav- ing been formed, like the grauwacke, of a fine detritus (matter washed from other rocks), and its having been deposited slowly ; although, as in the case of the grau- wacke, the arenaceous beds occasionally pass into coarse conglomerates. Indeed, until a recent period, this system was considered as a portion of the grau- wacke group, and as marking its passago into the gray micaceous beds of tho Old Bed Sandstone. Merely look- ing a cabinet specimens, it would bo impossible to is mguish between many of the grauwacke and silu- 'an..foc,,s’. but taking them in the mass, they are readily distinguishable. In the first place, their sedi- nln;,iaTChara<:tCr i8 very marked ; they present moro thov h lternat;ons from one kind of strata to another ; ReueraBv 1Ufinder“one] fcwer changes by heat; and are generally looser and moro earthy in their texture. The limestones are less crystalline than those of the early grauwackes; the arenaceous beds are also less siliceous, and more closely resemble ordinary sand- stones; while the abundance of organic remains justi- fies their arrangement into a separate system. The grauwacke forms the immediate surface in many large districts in Scotland, England, France, Germany, and North America, showing that, at the time of its formation, “some general causes were,in operation over a large portion of the northern hemisphere, and that the result was the production of a thick and extensive deposit, enveloping animals of similar organic structure over a considerable surface.” The igneous rocks asso- ciated with the transition series are chiefly granitic; effusions of trap making their appearance only among the later strata. Perhaps the most extensive and gigantic efforts of volcanic power were exhibited at tho close of this period; and there is abundant proof that all the principal mountain-chains in the world were then upheaved. The Grampian and Welsh ranges, the Pyrenees, Hartz mountains, Dofrafelds, Uralian, Himaleh, Atlas range, Mountains of the Moon, and other African ridges, the Andes, and Alle- ghanies—all seemed to have received their present elevation at the close of the transition period. Fossils of the Grauwacke and Silurian.—The fossils of the grauwacke and Silurian (a few of which ex- tend to the clayey and sandy slates immediately below) are of both plants and animals. Amongst the plants are algce, or sea-weeds, showing that seas like the present now existed. Some land plants are also found, but of the simpler structures—as filiccs, or ferns; equisetacece, a class of plants of the cha- racter of the mare’s-tail of our common marshes; and lycopodiacece, a class of the character of our club mosses. All of these land plants are monocotyledons; that is, produced from seeds of a single lobe, and therefore endo- genous, that is, growing from within—timber plants be- ing, on the contrary, the produce of two-lobed seeds, and growing by exterior layers. The Flora of this era thus appears of a very simple kind, indicating, gene- rally, low-lying and marshy habitats. . The animals are also, in general, of a humble and simple kind. There is abundance of those creatures (polypi) resembling plants, which fix themselves on the bottom of the sea by stalks, and send forth branch-like arms for the purpose of catching prey, which they con- vey into an internal sac, and digest. At present, these creatures abound in the bottoms of tropical seas, where they live by devouring minute impurities which have escaped other marine tribes, and thus perform a service analogous to that of earth-worms and other land tribes, the business of which is to clear off all decaying animal and vegetable matter. But the class of animals found in greatest numbers in the grauwacke series of rocks are shellfish, possibly because the remains of these crea- tures are peculiarly well calculated for preservation. All over the earth, wherever grauwacke and Silurian rocks are found, shellfish are found imbedded in vast quantities, proving that shellfish were universal at the time when that class of rocks were formed. Among the radiata or rayed animals, the crinoid or cncrinite family occur for the first time, these differing from other corals in the self-dependent nature of their struc- ture, their fixed articulated stalk, and floating stomach, furnished with movable rays for the seizure and reten- tion of their food. As we ascend in the silurian group, the shellfish become more numerous and distinct in form ; spirifers, terebratidee, and producUc, are every- where abundant; and chambered shells, like the exist- ing nautilus, begin to people the waters. It must be remarked, however, that the encrinites and chambered shells of this early period are not so numerous, so gi- gantic, or so elaborate in their forms as those of tho Secondary strata: it is in the mountain limestone group that the encrinites attain their meridian, and in the lias and oolito that the ammonites and nautili are most fully developed. Of the Crustacea of this era, the most interesting](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22012400_0001_0033.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)