Volume 1

Chambers's Information for the people / edited by William and Robert Chambers.

- Date:

- 1848-1849

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Chambers's Information for the people / edited by William and Robert Chambers. Source: Wellcome Collection.

35/824 page 25

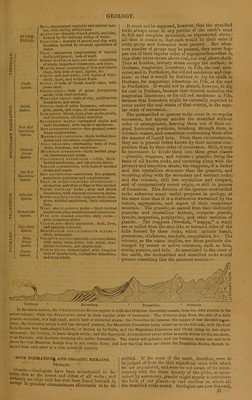

![Covered over, pressed upon, and converted, by bitumi- nous fermentation, into several varieties of coal. Two hypotheses have been advanced respecting the circumstances under which coal was formed. According to one, the vegetable matter must have grown in dense forests’and jungles for many years ; then the land must have sunk, and become the basin of a lake or estuary, in which situation rivers would wash into it mud and sand, which would cover over the vegetable mass, and form superincumbent beds of shale and sandstone respectively. Then the ground would be once more elevated, or sufficiently shoaled up, to become again a scene of luxuriant vegetation. When the vegetation had again become accumulated, the land would be again sunk, and become once more the basin of a lake, in which case the beds of mud and sand might again be formed by rivers. And this alternating process is sup- posed to have taken place as often as there are beds of coal to be accounted for. The other hypothesis is, that, into lakes and estuaries, rivers coming from different quarters would bring the various matters forming the strata of the carboniferous group—a river from one direction bringing the mud which would form shale, another from another direction the vegetable matter which would form coal, and so on, each deposit perhaps taking place through the efficacy of some local circum- stances, while the causes for the other deposits were temporarily suspended. Both theories are beset with difficulties ; and perhaps the true solution is to be found in a combination of the two. Estuary and lake deposits, inundating rivers, a high temperature, a pro- lific Flora, and frequent elevations and subsidences of the land, seem to have been the conditions under which the coal measures were deposited. Fossils of the Carboniferous Group.—In this group of rocks, upwards of 300 species of plants have been dis- covered, all of them now extinct. About two-thirds of them are ferns ; the others consist of large coniferce (allied to the pine), of gigantic lycapodiacece, of species allied to the cactece and euphorbiacece, and of palms. Most of these plants probably exist in the coal beds, forming, in fact, their sole composition ; but the pecu- liar nature of this mineral renders it difficult to detect them by examination. Thin slices, however, have been examined by the microscope, and the vegetable struc- ture has then been detected, where no external trace of it wa3 visible. In cannel coal, a kind peculiarly com- pact, the vegetable structure is observed throughout the whole mass, while the fine coal retains it only in small patches, which appear, as it were, mechanically entangled. Splint and cannel coal often bear distinct impressions of plants. The plants are such as grow in hot moist situations; and it is therefore presumed that a climate of that nature existed at an early period where coal is now found, even in Melville’s Island, which is within the polar circle. Large fragments of trees are often found in the shale and sandstone beds of the carboniferous group—more frequently in the former than in the latter. As usual with fossil substances, they are converted into the material in which they are imbedded, but preserve all their original lineaments, except that they are generally changed from their original round to a flattened form, the result of the pressure they have sustained. In most instances, these fragments of trees appear to have been transported from a distance, and laid down hori- zontally in their present situation ; but some have been found with their roots still planted in their native soil of mud, and the stems shooting upwards through several superior beds of various substances. Even in some coal beds, there are found stems of trees in their ongmal vertical position—the roots being imbedded in s iale beneath. In these instances, we must suppose e fossil to be on the spot where the living tree was •an ed,grew, and died. In the Bcnsham coal seam, f ,e ' arr°w coal-field, a few years ago, there was *1 • V ,ln uPt,gkt tree of the kind called lepidodendron, liin/f.'VV'^i a Jllllff«c‘wide at the base, and thirty- ec high, the branches at the top being also entire: the lepidodendron is so called from the scaly appear- ance of its stem, the scales being the roots of the leaf stalks, (see fig.). Various fossil trees have been dis- ]. Calamities; 2. Stigmaria ; 3. Lepidodendron. covered in the sandstone beds of the carboniferous group at Craigleith and Gran ton, in the county of Edinburgh. One found in Craigleith quarry was twenty feet long, three feet in diameter, with scars where the branches had been torn off, and was ascertained, by microscopic inspection of slices of the trunk, to have been a conifera of the existing genus Araucaria. The animal remains of the carboniferous group con- sist of zoophytes (corals, encrinites, &c.) in vast pro- fusion, of shellfish, Crustacea, and fishes. In the moun- tain limestone the crinoidea seem to have attained their meridian, for whole beds, many feet thick, and square miles in extent, are almost wholly composed of them ; hence the not unfrequent term, Encrinital Lime- stone. Shellfish univalve, chambered, and bivalve, also abound; the trilobite and Crustacea, allied to the modern chiton, are by no means uncommon ; and fishes of a gigantic size and sauroid structure are scattered throughout the strata both of the mountain limestone and the coal measures. New Red Sandstone System.—This series of strata, lying above the carboniferous system, comprehends rocks called the red conglomerate, formed of pieces of earlier rocks, some rough, some smoothed by rolling, all caked together; magnesian limestone, abounding in Germany and the north of England ; red or variegated sandstone, a group of many varieties of colour, and principally of argillaceous and siliceous consistence; muschelkalk, a limestone varying in texture, but most frequently gray and compact—not found in Britain or France, but occurring in Germany and Poland; and variegated marls—beds of different colours, red, blue, and gray, composed of the remains of shellfish. To these also belong beds or masses of rock salt, of which many exist in England, particularly in the county of Chester. Rock salt is a crystalline mass, forming irregular strata, sometimes of the thickness of several hundred feet. The substance is rarely pure, but generally contains some portion of argillaceous oxide of iron, which gives it a red colour. It is dug like coal and other minerals, and when dissolved and subjected to proper purification, is sold for domestic purposes. Fossils of the New Red Sandstone Group.—The vege- table remains of this group belong to the same families as those of the coal strata, only they are found very sparingly and of diminished dimensions; but in the department of animal life, when we arrive at the muschelkalk, or shell limestone, we find a great dif- ference, leading to a supposition that, at this era of geological chronology, circumstances had arisen chang- ing the character of marine life over certain portions of Europe ; that certain animals abounding previously, and for a great length of time, disappeared never to reappear, at least as far as we can judge from our knowledge of organic remains; and that certain new forms of a very remarkable kind were added. The new creatures were of such a class as we might expect to bo first added to the few specimens of fish which had hitherto existed: they were of the class of Reptiles—creatures whose organisation places them next](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22012400_0001_0035.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)