The technology of bread-making : including the chemistry and analytical and practical testing of wheat, flour, and other materials employed in bread-making and confectionery / by William Jago and William C. Jago.

- William Jago

- Date:

- 1911

Licence: In copyright

Credit: The technology of bread-making : including the chemistry and analytical and practical testing of wheat, flour, and other materials employed in bread-making and confectionery / by William Jago and William C. Jago. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The University of Leeds Library. The original may be consulted at The University of Leeds Library.

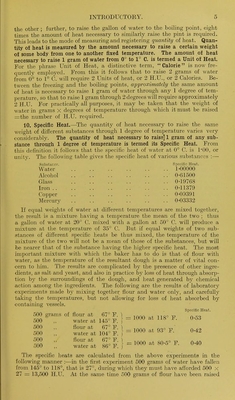

17/944 page 5

![the other ; further, to raise the gallon of water to the boiling point, eight times the amount of heat necessary to similarly raise the pint is required. This leads to the mode of measuring and registering quantity of heat. Quan- tity of heat is measured by the amount necessary to raise a certain weight of some body from one to another fixed temperature. The amount of heat necessary to raise 1 gram of water from 0° to 1° C. is termed a Unit of Heat. For the phrase Unit of Heat, a distinctive term, “ Calorie ” is now fre- quently employed. From this it follows that to raise 2 grams of water from 0° to 1° C. will require 2 Units of heat, or 2 H.U., or 2 Calories. Be- tween the freezing and the boiling points, approximately the same amount of heat is necessary to raise 1 gram of water through any 1 degree of tem- perature, so that to raise 1 gram through 2 degrees vdll require approximately 2 H.U. For practically all purposes, it may be taken that the weight of water in grams X degrees of temperature through which it must be raised =the number of H.U. required. 10. Specific Heat.—-The quantity of heat necessary to raise the same weight of different substances through 1 degree of temperature varies very considerably. The quantity of heat necessary to raise] 1 gram of any sub- stance through 1 degree of temperature is termed its Specific Heat. From tliis definition it follows that the specific heat of water at 0° C. is 1*00, or unity. The following table gives the specific heat of various substances :— Substance. W'ater Alcohol Glass Iron . . Copper Mercury Specific Heat. I-00000 0-61500 0-19768 0-11379 0-09391 0-03332 If equal weights of water at different temperatures are mixed together, the result is a mixture having a temperature the mean of the two ; thus a gallon of water at 20° C. mixed with a gallon at 50° C. wiU jtroduce a mixture at the temperature of 35° C. But if equal weights of two sub- stances of different specific heats be thus mixed, the temperature of the mixture of the two will not be a mean of those of the substances, but will be nearer that of the substance having the higher specific heat. The most important mixture with which the baker has to do is that of flour with water, as the temperature of the resultant dough is a matter of vital con- cern to him. The results are complicated by the presence of other ingre- dients, as salt and yeast, and also in j)ractice by loss of heat through absorp- tion by the surroundings of the dough, and heat generated by chemical action among the ingredients. The following are the results of laboratory experiments made by mixing together flour and water only, and carefully taking the temperatures, but not allowing for loss of heat absorbed by containing vessels. 500 grams of flour at 67° F. 500 ,, water at 145° F. 500 ,, flour at 67° F. 1 500 ,, water at 104° F. J 500 ,, flour at 67° F. 500 ,, water at 86° F. Specific Heat. 1000 at 118° F. 0-53 1000 at 93° F. 0-42 1000 at 80-5° F. 0-40 The specific heats are calculated from the above experiments in the following manner :—in the first experiment 500 grams of water have fallen from 145° to 118°, that is 27°, during which they must have afforded 500 X 27 = 13,500 H.U. At the same time 500 grams of flour have been raised](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21538700_0017.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)