Volume 1

A text-book of physiology / by Henry P. Bowditch [and others] ; edited by William H. Howell.

- Date:

- 1900

Licence: Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Credit: A text-book of physiology / by Henry P. Bowditch [and others] ; edited by William H. Howell. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

480/608 (page 476)

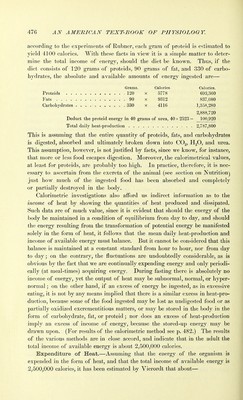

![according to the experiments of Rubner, each gram of proteid is estimated to yield 4100 calories. With these facts in view it is a simple matter to deter- mine the total income of energy, should the diet be known. Thus, if the diet consists of 120 grams of proteids, 90 grams of fat, and 330 of carbo- hydrates, the absolute and available amounts of energy ingested are— Grams. Calories. Calories. Proteids 120 x 5778 693,360 Fats 90 X 9312 837,080 Carbohydrates 330 x 4116 ],3-58,280 2,888,720 Deduct the proteid energy in 40 grams of urea, 40 x 2523= 100,920 Total daily heat-production 2,787,800 This is assuming that the entire quantity of proteids, fats, and carbohydrates is digested, absorbed and ultimately broken down into CO2, H2O, and urea. This assumption, however, is not justified by facts, since we know, for instance, that more or less food escapes digestion. Moreover, the calorimetrical values, at least for proteids, are probably too high. In practice, therefore, it is nec- essary to ascertain from the excreta of the animal (see section on Nutrition^ just how much of the ingested food has been absorbed and completely or partially destroyed in the body. Calorimetric investigations also afford us indirect information as to the income of heat by showing the quantities of heat produced and dissipated. Such data are of much value, since it is evident that should the energy of the body be maintained in a condition of equilibrium from day to day, and should the energy resulting from the transfoi-mation of potential energy be manifested solely in the form of heat, it follows that the mean daily iieat-production and income of available energy must balance. But it cannot be considered that this balance is maintained at a con.stant .standard from hour to hour, nor from day to day; on the contrary, the fluctuations are undoubtedly considerable, as is obvious by the fact that we are continually expending energy and only periodi- cally (at meal-times) acquiring energy. During fasting there is absolutely no income of energy, yet the output of heat may be subnormal, normal, or hyper- normal ; on the other hand, if an excess of energy be ingested, as in excessive eating, it is not by any means implied that there is a similar excess in heat-pro- duction, because some of the food ingested may be lost as undigested food or as partially oxidized excrementitious matters, or may be stored in the body in the form of carbohydrate, fat, or proteid; nor does an excess of heat-production imply an excess of income of energy, because the stored-up energy may be drawn upon. (For results of the calorimetric method see p. 482.) The results of the various methods are in close accord, and indicate that in the adult the total income of available energy is about 2,500,000 calories. Expenditure of Heat.—Assuming that the energy of the organism is expended in the form of heat, and that the total income of available energy is 2,500,000 calories, it has been estimated by Vierordt that about—](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21981735_0001_0482.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)