Volume 1

Spons' encyclopaedia of the industrial arts, manufactures, and raw commercial products / edited by Charles G. Warnford Lock.

- Spon, Edward.

- Date:

- 1882

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Spons' encyclopaedia of the industrial arts, manufactures, and raw commercial products / edited by Charles G. Warnford Lock. Source: Wellcome Collection.

19/1100 (page 7)

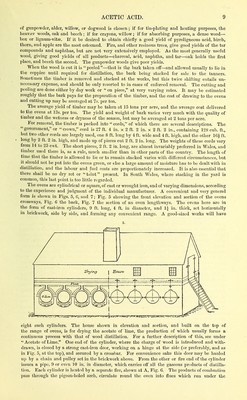

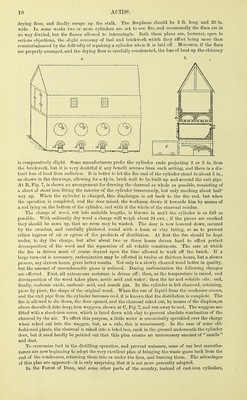

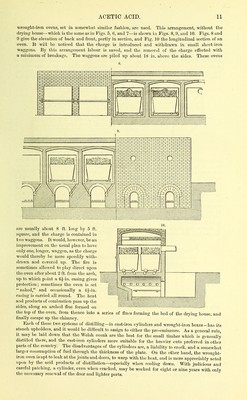

![similar in constitution to ammonia, pepsin, or the diastase of beer. Differing from these theories as to the nature and work of the m5'Coderm, Liebig and otlier eminent chemists regard the process of fermentati(m as one of the simplest alcoholic oxidation, and certainly wood shavings wliich have been used for many years in the manufacture of vinegar have been examined under the microscope without finding a trace of fungus upon them. The souring of wine is an everyday and natural illustration of the process of acetous fer- mentation, strong wines souring more readily than weak because tliey contain less vegetable matter in proportion to absolute alcohol. During acetous fermentation a substance called aldehyde—a lower compound of alcohol and oxygen—is probably always formed. Aldehyde is an exceedingly unstable body, and to prevent loss of acetic acid through its volatilization it is advisable to bring the ferment and alcohol together with as free ad- mixture of air as possible, that a rapid and more perfect oxidation may be ensured. The German, or quick vinegar process, effects this in the following manner. A vessel is prepared of the description shown in Fig. 4, varying in size from 13 ft. high and 15 ft. in diameter to 8 ft. liigli and 6 ft. in diameter, a large size being preferred. This tun (essigbilder, or vinegar generator or graduator) is care- fully hooped, and set up on any convenient jjlatform. A cover, fitting loosely on the top, keeps out dust and dirt, and about 12 in. below this is a fixed shelf, perforated with a great number of small holes and two or three larger ones. In the small holes are suspended pieces of thread or string, kept in their place by knots at the upper end. In the larger holes are fitted short glass or wooden tubes which go through the cover and serve as vents. About 18 in. from the bottom of the generator is fixed a second per- forated shelf or false bottom, and some few inches above this the sides of the tub are pierced with holes 1| in. in diameter which admit the necessary supply of air. Below the false bottom is an exit pipe for the liquid, preferably curving upwards when it reaches the outside until close upon the level of the air-holes. Finally, the generator is filled from the false bottom to within a short distance of the top shelf witli shavings, chips of beech wood, or charcoal. The latter is preferable, as presenting a greater surface for oxidation than any other substance, but it requires frequent renewal,—not admitting of being cleansed. If shavings or chips are employed, they should be boiled in water and dried in a close oven before being used. Before passing the alcoholic liquors into the generator, the shavings, and the vessel itself, are soured with hot strong vinegar to accelerate the subsequent oxidation. The alcoholic liquors, usually consisting of 50 gallons of brandy of 60 per cent and 37 gallons of beer with about -j-J^^th of ferment, are now introduced into the generator through a funnel in the cover shown at A, Fig. 4. The liquors percolate slowly through the shavings, chips, or charcoal, meet an ascending current.of air, and undergo oxidation. Flowing over through the exit siphon they are returned once more to traverse the generator, or are ti-ansferred to a second similar apparatus,—the latter being the preferable plan. By this quick process, practised largely in Germany, France, and England, as much as 150 gallons of vinegar can be manufactured per diem in 10 tuns of the description shown in the drawing. The liquors should be as clear as ])ossible—free from suspended organic substances—or else the chips or shavings become rapidly choked, and unless these are constantly cleaned by boiling in water, or renewed, equal distribution of the liquors is impossible. No pyroligneous acid, with admixture of tarry matters and oils, should be present, as they prevent oxidation. The nitrogenous organic substances having promoted the acetification of the alcohol, settle out and then assume a new form ; they are known as mother of vinegar. Treated with potash this mother, a white gelatinous mass, loses its nitrogen, pure cellulose being left. Further details of the process, and modifications of it—such as Ham's—concern rather the manufacturer of vinegar than of acetic acid, and these, together with further details relating to acetous fermentation, will be dealt with at length in a separate article upon vinegar. It should be noted that simple oxidation of alcohol—by the carefully regulated action of air or an oxidizing agent—produces pure acetic acid, but in the ordinary acetous fermentation, where certain vegetable bodies are present, the acid is yielded in the form of vinegar by admixture with various organic impurities. Pyuoligneods Acid (Lat. Acidum xiyi'oUgnosum ; Ger. Ilohsduro or Hoh-essig ; Fr. Acide pyro- ligneux). The impure or pyroligneous acid is obtained by the dry distillation of wood in close ovens. From the first di.stillation it is a dark, yellowish-brown liquid of varying strength, possessing an uupleasant clinging odour from the tarry compounds and various resinous matters with which it is more or less impregnated. The manufacture is carried on extensively in various parts of this country,](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21780572_0001_0019.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)