On the sensations of tone as a physiological basis for the theory of music / by Hermann L.F. Helmholtz ; translated, thoroughly revised and corrected, rendered conformable to the 4th (and last) German edition of 1877, with numerous additional notes and a new additional appendix bringing down information to 1885, and especially adapted to the use of musical students, by Alexander J. Ellis.

- Hermann von Helmholtz

- Date:

- 1895

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: On the sensations of tone as a physiological basis for the theory of music / by Hermann L.F. Helmholtz ; translated, thoroughly revised and corrected, rendered conformable to the 4th (and last) German edition of 1877, with numerous additional notes and a new additional appendix bringing down information to 1885, and especially adapted to the use of musical students, by Alexander J. Ellis. Source: Wellcome Collection.

55/604 (page 31)

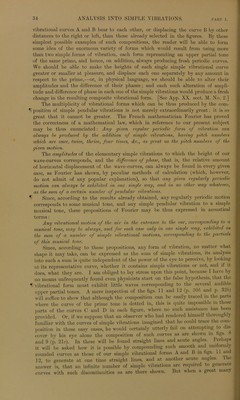

![taking sections consisting of two periods of B, we divide B into larger sections, each of which is of the same horizontal lengtli, and hence corresponds to the same duration of time, as the sections of A. If, then, both simple tones are heard at once, and the times of the points e and d„, e and 8, e, and 8, coincide, the heights of the portions of the section of cnrve e e liave to be [algebraically] added to heights of the section of curve d„8, and similarly for the sections e e, and 8 8,. The result of this addition is sho\vn in the curve C. The dotted line is a duplicate of the section d0S in the curve A. Its object is to make the composition of the two sections immediately evident to the eye. It is easily seen that the curve C in every place rises as much above or sinks as much below the curve A, as the curve B respectively rises above or sinks beneath the horizontal line. The heights of the curve C are consequently, in ac- cordance with the rule for compounding vibrations, equal to the [algebraical] sum of the corresponding heights of A and B. Thus the perpendicular C! in C is the IT sum of the perpendiculars a, and b, in A and B ; the lower part of this perpen- dicular Cd from the straight line up to the dotted curve, is equal to the perpen- dicular a1( and the upper part, from the dotted to the continuous curve, is equal to the perpendicular b(. On the other hand, the height of the perpendicular c2 is equal to the height a2 diminished by the depth of the fall b2. And in the same way all other points in the curve C are found.* It is evident that the motion represeuted by the curve C is also periodic, and that its periods have the same duration as those of A. Thus the addition of the section du8 of A and e e of B, must give the same result as the addition of the perfectly equal and similar sections 8 and e e„ and, if we supposed both curves to be continued, the same would be the case for all. the sections into which they would be divided. It is also evident that equal sections of both curves could not continually coincide in this way after completing the addition, unless the curves thus added could be also separated into exactly equal and similar sections of the same If length, as is the case in fig. 11, where two periods of B last as long or have the same horizontal length as one of A. Now the horizontal lengths of our figure represent time, and if we pass from the curves to the real motion s, it results that the motion of air caused by the composition of the two simple tones, A and B, is also periodic, just because one of these simple tones makes exactly twice as many vibrations as the other in the same time. It is easily seen by this example that the peculiar form of the two curves A and B has nothing to do with the fact that their sum C is also a periodic curve. hatever be the form of A and B, provided that each can be separated into equal and similar sections which have the same horizontal lengths as the equal and similar sections of the other—no matter whether these sections correspond to one or two, or three periods of the individual curves-then any one section of the curve A compounded with any one section of the curve B, will always give a section simikr r ’ I the Same lenSth> and will be precisely equal and IT } f aUJ .0ther sectl0n of the curve C obtained by compounding any other section of A with any other section of B. ^ When such a section embraces several periods of the corresponding curve (as in theJ the^niteb 1£' ^ C°USist °f tW° periods of tlie simPle tone B), then the pitch of this second tone B, is that of an upper partial tone of a prime (as the simple tone A in fig. 11), whose period has the length of that nrinciml section, in accordance with the rule above cited. pnnupal „ order t0 g-ea slight conception of the multiplicity of forms producible bv “?rrry “,mP “n’I'08iti»8' 1 »V »»* that the compoundItetuld 8truc ^d- nfot u®ed to geometrical con- thfl iwn «trongly recommended to trace .»»OB, Md to construct the on mp ii , > uunsürueü tno nornpr^i' i fc^em’ by drawing a numbor of 2S arS n a Stlraight line> and then settmg off upon them the lengths of tho corre- sponding perpendiculars in A and B in proper directions, and joining the extremities of the lengths thus found by a curved line. In this way only can a clear conception of tho com- Position of vibrations be ronderod sufficieutly familiär for subsequent use.—Translator.] '](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b28141532_0055.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)