Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The elements of experimental chemistry. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the National Library of Medicine (U.S.), through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the National Library of Medicine (U.S.)

102/802

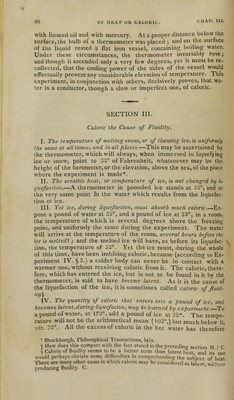

![with linseed oil and with mercury. At a proper distance below the surface, the bulb of a thermometer was placed ; and on the surface of the liquid rested a flat iron vessel, containing boiling water. Under these circumstances, the thermometer invariably rose; and though it ascended only a very few degrees, yet it must be re- collected, that the cooling power of the sides of the vessel would effectually prevent any considerable elevation of temperature. This experiment, in conjunction with others, decisively proves, that wa- ter is a conductor, though a slow or imperfect one, of caloric. SECTION III. Caloric the Cause of Fluidity. I. The temjierature of melting snow, or of thawing ice, is uniformly the same at all times, and in all places.—This may be ascertained by the thermometer, which will always, when immersed in liquefying ice or snow, point to 32° of Fahrenheit, whatsoever may be the height of the barometer, or the elevation, above the sea, of the place where the experiment is made*. II. The sensible heat, or temjierature of ice, is not changed by li- quefaction.—A thermometer in pounded ice stands at 32°, and at the very same point in the water which results from the liquefac- tion ot ice. III. Yet ice, during liquefaction, must absorb much caloric.—Ex- pose a pound of water at 32°, and a pound of ice at 32°, in a room, the temperature of which is several degrees above the freezing point, and uniformly the same during the experiment. The water will arrive at the temperature of the room, several hours before the ice is melted] ; and the melted ice will have, as before its liquefac- -. tion, the temperature of 52°. Yet the ice must, during the whole of this time, have been imbibing caloric, because (according to Ex- periment IV. § 2.) a colder body can never be in contact with a warmer one, without receiving caloric from it. The caloric, there- fore, which has entered the ice, but is not to be found in it by the thermometer, is said to have become latent. As it is the cause of the liquefaction of the ice, it is sometimes called caloric of fluid- ity\ IV. The quantity of caloric that enters into a pound of ice, and becomes latent,during liquefacion, may be learned by exfierimciit. To a pound of water, at 172°, add a pound of ice at 32°. The tempe- rature will not be the arithmetical mean (102°,) but much below it, viz. 32°. All the excess of caloric in the hot water has therefore * Shuckburgh, Philosophical Transactions, Ixix. -J- How does this comport with the fact stated in the preceding' section 11 ? C $ Caloric of fluidity seems to be a better term than latent heat, and its use would perhaps obviate some difficulties in comprehending the subject of heat There are many other cases in which caloric may be considered as latent, without producing fluidity. C.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21128170_0102.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)