Maternity services. Volume II, Minutes of evidence.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. Health Committee

- Date:

- 1992

Licence: Open Government Licence

Credit: Maternity services. Volume II, Minutes of evidence. Source: Wellcome Collection.

47/320 (page 379)

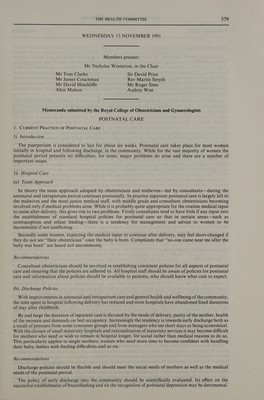

![WEDNESDAY 13 NOVEMBER 199] Members present: Mr Nicholas Winterton, in the Chair Mr Tom Clarke Sir David Price Mr James Couchman Rev Martin Smyth Mr David Hinchliffe Mr Roger Sims Alice Mahon Audrey Wise Memoranda submitted by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists POSTNATAL CARE 1. CURRENT PRACTICE OF POSTNATAL CARE li Introduction The puerperium is considered to last for about six weeks. Postnatal care takes place for most women initially in hospital and following discharge, in the community. While for the vast majority of women the postnatal period presents no difficulties, for some, major problems do arise and there are a number of important issues. lii_ Hospital Care (a) Team Approach In theory the team approach adopted by obstetricians and midwives—led by consultants—during the antenatal and intrapartum period continues postnatally. In practice inpatient postnatal care is largely left to the midwives and the most junior medical staff, with middle grade and consultant obstetricians becoming involved only if medical problems arise. While it is probably quite appropriate for the routine medical input to cease after delivery, this gives rise to two problems. Firstly consultants tend to have little if any input into the establishment of standard hospital policies for postnatal care so that in certain areas—such as contraception and infant feeding—there is a tendency for management and advice to women to be inconsistent if not conflicting. Secondly some women, expecting the medical input to continue after delivery, may feel short-changed if they do not see “their obstetrician” once the baby is born. Complaints that “no-one came near me after the baby was born” are heard not uncommonly. Recommendations Consultant obstetricians should be involved in establishing consistent policies for all aspects of postnatal care and ensuring that the policies are adhered to. All hospital staff should be aware of policies for postnatal care and information about policies should be available to patients, who should know what care to expect. (b) Discharge Policies With improvements in antenatal and intrapartum care and general health and wellbeing of the community, the time spent in hospital following delivery has reduced and most hospitals have abandoned fixed durations of stay after childbirth. By and large the duration of inpatient care is dictated by the mode of delivery, parity of the mother, health of the neonate and demands on bed occupancy. Increasingly the tendency is towards early discharge both as a result of pressure from some consumer groups and from managers who see short stays as being economical. With the closure of small maternity hospitals and rationalisation of maternity services it may become difficult for mothers who need or wish to remain in hospital longer, for social rather than medical reasons to do so. This particularly applies to single mothers, women who need more time to become confident with handling their baby, babies with feeding difficulties and so on. Recommendations Discharge policies should be flexible and should meet the social needs of mothers as well as the medical needs of the postnatal period. The policy of early discharge into the community should be scientifically evaluated. Its effect on the successful establishment of breastfeeding and on the recognition of postnatal depression may be detrimental.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b32222907_0047.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)