Maternity services. Volume II, Minutes of evidence.

- Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. Health Committee

- Date:

- 1992

Licence: Open Government Licence

Credit: Maternity services. Volume II, Minutes of evidence. Source: Wellcome Collection.

48/320 (page 380)

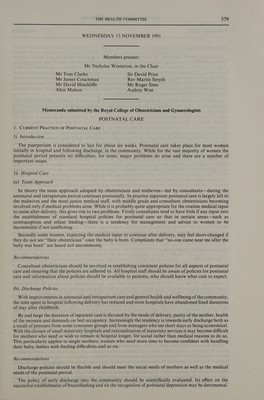

![13 November 1991 ] | [Continued liii Community Care Community care is shared by the general practitioner, the community midwives and health visitors. Midwives rule No. 27 states that “the postnatal period means a period of not less than 10 and not more than 28 days after the end of labour during which the continued attendance of a midwife on the mother and baby is required” (1). This has been interpreted by the providers as a daily visit to all postnatal mothers and babies until at least the tenth postnatal day. In practice many mothers who are seen to be coping well are not visited every day while mothers with problems may continue to see the midwife regularly until the twenty-eighth day following delivery. Health visitors are notified of the delivery and visit on or around the tenth day and thereafter according to the perceived needs of the family. General practitioners receive item of service payments for five visits to be made during the first fifteen days after delivery and for undertaking a postnatal examination—usually done in the surgery—at around six weeks after delivery. Most GPs do not make five home visits within the first two weeks and it is doubtful whether this is a sensible arrangement since most mothers have few problems and are already seeing the midwife. It is likely though that with the increasing tendency of GPs to run their practices as business concerns that all five ‘“‘visits”’ will increasingly be made and claimed for. Conversely in some parts of the country there now seems to be a fixed upper limit on the number of visits a health visitor may make during the baby’s first year of life. The standard of care delivered in the community varies. One study in N. Hertfordshire reported that 50 per cent of patients were dissatisfied with their postnatal care (2). In a study undertaken in S.E. Scotland (3) only 40 per cent of GPs in seventy-seven training practices noted delivery dates in practice diaries—the majority relied on being informed of the delivery by the patient, her husband or by the hospital. Only a handful of GPs visited the mother in hospital and 30 per cent did not visit after discharge—relying on midwives visits or the mother coming to the surgery. While over 90 per cent of the GPs felt that there was a team approach to postnatal care in the community this belief was not supported by the other members of the team—the midwives, health visitors and practice nurses. If a mother is discharged from hospital before 48 hours after delivery the GP is obliged to make an early home visit. Most of these early discharges are arranged during the antenatal period but if not there can be problems with informing the GP of the mother’s departure from hospital. There appears to be no standardised procedure of informing the GP when a mother and baby have been discharged. Recommendations An integrated team approach between midwife, health visitor, GP and hospital with an excellent standard of communication between all parties is essential to maintain a high standard of postnatal care. Standard, effective policies for informing a practice of a mother’s discharge must be established and the local GPs and their teams should be aware of the hospital’s policies for postnatal care so that patient management may be consistent. 2. SPECIFIC ISsUES/PROBLEM AREAS 21 Infant Feeding The most recent national data on infant feeding comes from the OPCS survey last undertaken in 1985 (4). Between 50 per cent and 60 per cent of women in the United Kingdom choose to breastfeed their baby but the great majority give up in the early post partum weeks, by six weeks only 40 per cent of women are still breastfeeding. Howie et al 1990 (5) demonstrated that there is a significant reduction in the incidence of gastrointestinal disease in children during the first year of life if they are partially breastfed for more than 13 weeks after delivery. There is now mounting evidence to suggest that even in developed countries breastfeeding really does improve infant health. Efforts are being made to encourage breastfeeding. The DHSS in collaboration with the voluntary organisations—particularly the National Childbirth Trust (NCT)—have mounted a countrywide breastfeeding initiative but it is low key and tends to preach to the converted. There is also a move to curtail the advertising of artificial baby milks and to force manufacturers to inform women buying these formula feeds that ‘“‘breast is best’’. Breastfeeding is not easy and its successful establishment depends on good instruction during the early postnatal days, commitment on the part of the mother and support from the rest of the family, particularly the husband. Infant feeding is not often discussed in depth antenatally except at specially arranged classes which a minority of mothers attend. After delivery instruction and assistance is left to the midwives—most of whom have never had children. Mothers usually see a large number of different midwives during their stay in hospital and advice is often inconsistent. Moreover many mothers are discharged home before lactation is established. No provision is made for mothers having difficulties and very few hospitals offer breastfeeding problem clinics. Once home more advice—often conflicting—comes from a different set of midwives and a health visitor as well as from a host of friends and relatives. Small wonder that most women give up. Mothers most likely to establish successful breastfeeding and to maintain it for more than thirteen weeks are those who use](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b32222907_0048.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)