Volume 1

A dictionary of Christian antiquities : being a continuation of the 'Dictionary of the Bible' / edited by William Smith and Samuel Cheetham ; illustrated by engravings on wood.

- Date:

- [between 1890 and 1899?]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A dictionary of Christian antiquities : being a continuation of the 'Dictionary of the Bible' / edited by William Smith and Samuel Cheetham ; illustrated by engravings on wood. Source: Wellcome Collection.

1005/1096 (page 985)

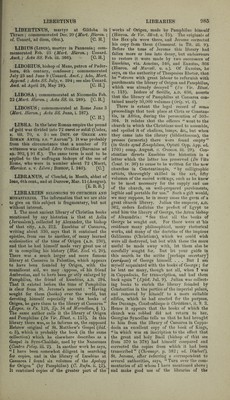

![LIBERTINUS, martyr at Gildoba in Thrace ; commemorated Dec. 20 {Mart, flieron.; cf. Usuard, ad diem, Obss.). [C. H.] LIBIUS (Libus), martyr in Pannonia; com- memorated Feb. 23 {Mart. Hieron.; Usuard. Auct.; Acta SS. Feb. iii. 366). *< [C. H.] LIBORIUS, bishop of Mans, patron of Pader- born, 4th century, confessor; commemorated July 23 and June 9 (Usuard. Auct. ; Ado, Mart. Append.; Acta SS. July, v. 394; see also Usuard. Auct. ad April 28, May 28). [C. H.] LIBOSA; commemorated at Nicomedia Feb. 22 {Mart. Hieron.; Acta SS. iii. 289). [C. H.] LIBOSUS; commemorated at Rome June 3 {Mart. Hieron.; Acta SS. June, i. 287). [C. H.] LIBRA. In the later Roman empire the pound of gold was divided into 72 aurei ov solidi {Go&qx, X. tit. 70, s. 5: see DiCT. OF Greek vVnd Roman Antiq. s.v. “ Aurum”). It was probably from this circumstance that a number of 72 witnesses was called Libra Occidna (Baronius ad an. 302, § 91 ff.). The same term is said to be applied to the suffragan bishops of the see of Rome, who wei’e in number about 72 (Macri, Hierolex. s. v. Libra; Bishop, I. 240). [C.] LIBRANUS, of Clonfad, in Meath, abbat of Iona, 6th cent., and at Durrow, Mar. 11 (Aengus). [E. B. B.] LIBRARIES BELONGING TO CHURCHES AND MONASTERIES. The information that we are able to give on this subject is fragmentary, but not without intei’est. I. The most ancient library of Christian books mentioned by any historian is that at Aelia (Jerusalem), collected by Alexander, the bishop of that city, a.d. 212. Eusebius of Caesarea, writing about 330, says that it contained the epistles, from one to another, of many learned ecclesiastics of the time of Origen (a.d. 230), and that he had himself made very great use of it in compiling his history {Hist. Eccl. vi. 20). There was a much larger and more famous library at Caesarea in Palestine, which appears to have been founded by Origen, with the munificent aid, we may suppose, of his friend Ambrosius, and to have been grratly enlarged by Pamphilus, the friend of Eusebius, A.D. 294. That it existed before, the time of Pamphilus is clear from St. Jerome’s account: “ Having sought for them (books) over the world, but devoting himself especially to the books of Origen, he gave them to the library at Caesarea ” {Expos, in Ps. 126, Ep. 34 ad Marcellam., § 1). The same author calls it the library of Origen and Pamphilus {De Yir. Illust. c. 113). In this library there was, as he informs us, the supposed Hebrew original of St. Matthew’s Gospel {ibid. c. 3), which is probably the book (in the same collection) which he elsewhere describes as a Gospel in Syro-Chaldaic, used by the Nazarenes {Contra Pelag. iii. 2). In another work he says, “ I have been somewhat diligent in searching for copies, and in the library of Eusebius at Caesarea I found six volumes of the Apology for Origen ” (by Pamphilus) {C. Rufin. ii. 12). It contained copies of the greater part of the works of Origen, made by Pamphilus himself (Hieron. de Vir. IWist. c. 75). The originals of the Hexipla were there, and Jerome corrected his copy from them {Comment, in Tit. iii. 9). Before the time of Jerome this library had fallen more or less into decay, but endeavours to restore it were made by two successors of Eusebius, viz. Acacius, 340, and Euzoius, 366 (Hieron. ad Marcell. u. s.). Of Euzoius, he says, on the authority of Thespesius Rhetor, that he “ strove with great labour to refurnish with parchments the library of Origen and Pamphilus, which was already decayed” {I'e Vir. Illust. c. 113). Isidore of Seville, a.d. 636, asserts that the library of Pamphilus at Caesarea con- tained nearly 30,000 volumes {Orig. vi. 6). There is extant the legal record of somv proceedings that took place at Cirta or Constan- tia, in Africa, during the persecution of 303- 304. It relates that the officers “ went to the church in which the Christians used to assemble, and spoiled it of chalices, lamps, &c., but when they came into the library (bibliothecam), the presses (armaria) there were found empty” (in Gesta apud Zenophilum., Optati 0pp. App. ed. 1703; comp. August, c. Crescon. m. 29). Con- stantine directs Eusebius the historian in a letter which the latter has preserved {De Vita Const, iv. 36) to cause to be written for the new churches in Constantinople, “ by calligraphic artists, thoroughly skilled in the art, fifty volumes of the sacred writings, such as he knew to be most necessary for the supply and use of the church, on well-prepared parchments, legible and portable for use.” Such a gift would, we may suppose, be in many cases the germ of a great church library. Julian the emperor, A.D. 362, orders Ecdicius the prefect of Egypt to send him the library of George, the Arian bishop of Alexandria: “See that all the books of George be sought out. For there were at 'his residence many philosophical, many rhetorical works, and many of the doctrine of the impious Galilaeans (Christians), which we could wish were all destroyed, but lest with these the more useful be made away with, let them also be carefully sought for. But let your guide in this search be the scribe [perhaps secretary] {uorapios) of George himself . . . But I am myself acquainted with the books of George ; for he lent me many, though not all, when I was in Cap])adocia, for transcription, and had them back again ” {Epist. Jul. 9). Julian was collect- ing books to enrich the library founded by Constantins in the portico of the imperial palace, and remov'ed by himself to a more suitable edifice, which he had erected for the purpose. See Ducange, Constantiaopo is Christiana., ii. 9. 3. Hence it appears that the books of which the church was robbed did not x’eturn to her. Georgius Syncellus tells us that he had brought to him from the library of Caesarea in Cappa- docia an excellent copy of the book of Kings, “ in which was an inscription to the effect that the great and holy Basil (bishop of that see from 370 to 378) had himself compared and corrected the copies from which it had been transcribed” {Chronogr. p. 382; ed. Dindorf). St. Jerome, after referring a correspondent to several authorities, says, “ Turn over the com- mentaries of all whom I have mentioned above; and make good use of the libraries of the](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b2901007x_0001_1005.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)