Volume 1

A dictionary of Christian antiquities : being a continuation of the 'Dictionary of the Bible' / edited by William Smith and Samuel Cheetham ; illustrated by engravings on wood.

- Date:

- [between 1890 and 1899?]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A dictionary of Christian antiquities : being a continuation of the 'Dictionary of the Bible' / edited by William Smith and Samuel Cheetham ; illustrated by engravings on wood. Source: Wellcome Collection.

1006/1096 (page 986)

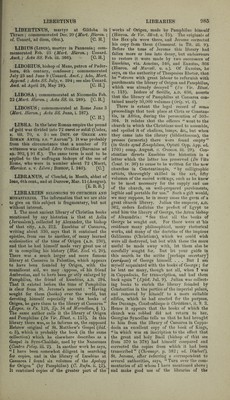

![churches; and thou wilt arrive more quickly at that which thou desirest and hast begun ” {Epist. ad J'ammach. 49, § 3; comp, Epist. 112, ad A'lgust. § 19). St. Augustine, writing at Hippo about the year 428, says, -‘I have heard that the holy Jerome w’rote on heresies ; but neither have we been able to find that little work of his in our own library, nor do we know from where it may be obtained ” (Z>e Haer. sub fin.) When Augustine was dying, “he directed that the library of the church and all the books should be carefully kept for posterity for ever.” He also left libraries to the church, “ con- taining books and treatises by himself or other holy persons ” (Possid. Vita Aug. 31). Theo- dosius the younger, 408-450, “ collected the sacred books and their interpreters so diligently, as not to come behind Ptolemy ” (Niceph. Call. Eist. Eccl. xiv. 3). Whether his collection was for the imperial library or the Patriarchium, we are not told; but the fact is worth noting, because it shews the spirit of the age. The leading ecclesiastics would not be behind the emperor. Hilary of Rome, a.d. 461, according to the Liber Pontificalis, “made two libraries in the Lateran baptistery ” (Anast. Vit. Pont. 47). From the same authority we learn that the w'orks of Gelasius, a.d. 482, were “ kept laid up in the library and archive of the church ” down to the 9th century (n. 50). Gregory I. A.D. 598, replying to the request of Eulogius of Alexandria that he would send him the Acts of the Martyrs collected by Eusebius, says, “ Besides those things which are contained in the books of Eusebius himself concerning the deeds of the holy martyrs, I know none in the archives of this our church, or in the libraries of the city of Rome, except a few collected in the roll of a single book ” {Epist. vii. 29). A narrative assigned to the year 649 or thereabout, shews that there was at that time a library already attached to St. Peter’s. It is said that w’hen Taio, bishop of Saragossa, who had been sent from Spain by king Chindasuind to procure the latter part of the Moralia of Gregory, could not learn from the pope or anyone else where it w'as, the very press in w'hich it lay was pointed out to him in a vision, as he watched and prayed by night in that church {De Visione, etc., Labb. Cone. ^v. 1844). Willibald, a.d. 76Q, in the life of St. Boniface, says that the four books of St. Gregory were to his day put into the “ libraries of churches ” (Pertz, Monum. Germ. Hist. ii. 334). At this period, and earlier, as we learn from an epistle of Taio, above mentioned, few books were composed or copied in the west, and all w'ere in danger of destruction, from the constant wars which desolated the Latin world {Epist. ad Quiricum ; Praefat. Saec. ii. 0. S. B. § v. Iv. 17). His evidence refers to Spain, but the evil was felt at Rome equally, as we learn from a state- ment of the Roman synod in 680, to the empe- rors who had convened the 3rd council of Con- stantinople. After describing themselves as “settled in the northern and western parts” of the empire, the Latin bishops say, “ We do not think that any one can be found in our time who can boast of great knowledge, seeing that in our I'egions the fury of various nations is everv day raging, now in fighting, now in overrunning and plundering; whence our whole life is full of care, surrounded as we are by a band of nations, ! and having to live by bodily toil, the ancient maintenance of the churches having by degrees fallen away and failed through divei's calamities ” (Labbe, vi. 681). Agatho, then bishop of Rome, made this an excuse for the ignorance of his legates, whom he sent to the council, as he said, “ out of the obedience which he owed ” to the emperors, “ not from any confidence in their knowletlge ” {ibid. 634). Bede {De Temp. Rat. 66, followed by Hincmar, Opusc. 20 c. Hincm. Laud.) says that when they arrived at Constan- tinople they were “ very kindly received by the most reverend defender of the Catholic faith Con- .stantiue (Pogonatus), and by him exhorted to lay aside philosophical [om. Hincm.] disputations, and to seek the truth in peaceable conference, all the books of the ancient fathers which they asked for being supplied them out of the library .at Constantinople.” The records of the council tell us that the same legates besought the emperor that the “ original books of the pa- tristic testimonies adduced might be brought from the Patriarchium ” {Act. \i. Labb. vi. 719) ; and we find the bishop of Constantinople himself speaking of the “ books of the holy and approved fathers which were laid up in his Patriarchium {Act. viii. ibid. 730; comp. 751, 780). A large number of extracts from the fathers are said to have been compared with the originals in the “ library of the Patriarchium ” (Aci. x. coll. 788, 790, 798, &c.) Several testimonies alleged are also said to have been compared with a “ silver-bound parchment book belonging to the (TK(vo(pv\dKiov of the most holy high church ” in the same city {ibid. 813, 814, &c.). There was at Constantinople also a registry or repository of documents {xapTo<pv\dKiov, u.s. 963) under the charge of an officer called the {ibid.). Whether this was a department of the library or distinct from it does not appear. The great esteem in which the church library at Con- stantinople was held by all parties is attested by the fact that the iconolater Theophanes refused to look at a copy of Isaiah, brought from the emperor’s library, alleging that all his books were corrupted, but asked for one from the library of the Patriarchium instead {Continuation iii. 14). For some centuries after this the Greeks possessed advantages for the acquisition of knowledge over the Latins ; though there were many in the' west, especially among the bishops, who employed themselves in collecting and multiplying good books. Thus Bede says of Acca, who succeeded Wilfrid at Hexham, a.d. 710, that he “ gathered together the histories of the sufterings (of the martyrs, &c.), with other ecclesiastical books most diligently, and made there a very large and noble library ” {Hist. Eccl. V. 20). Egbertus, bishop of York from 732-766, is another example in our own country. Alcuin, in 796, writing to Charlemagne from Tours, where he had oj^ned a school, says, “ I am partly in want of books of scholastic erudi- tion, that are somewhat difficult to be procured, which I had in my own country, through the good and most devoted diligence of my master, or my own labour, such as it was.” He there- fore desired that some youths might be sent into Britain to bring back whatever was neces- sary, “ that there might not only be ‘ a garden ! endosed’ at York, but that there may be at](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b2901007x_0001_1006.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)