Volume 1

A dictionary of Christian antiquities : being a continuation of the 'Dictionary of the Bible' / edited by William Smith and Samuel Cheetham ; illustrated by engravings on wood.

- Date:

- [between 1890 and 1899?]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A dictionary of Christian antiquities : being a continuation of the 'Dictionary of the Bible' / edited by William Smith and Samuel Cheetham ; illustrated by engravings on wood. Source: Wellcome Collection.

1008/1096 (page 988)

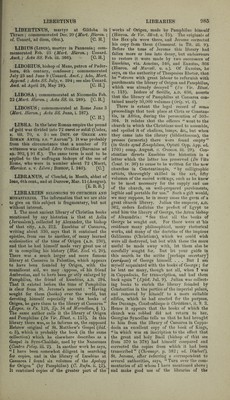

![its promulgation, the famous Rabanus Maurus built a library there, which he amply stored with books ( Vita per Rodolf. in Cave, Hist. Litt. nom. Raban). A beginning had been made, how- ever, so far back as 754. When Boniface, the Apostle of Germany, was murdered Iiy the Pagans at Dokem in east Frisia, they “ broke open the repository of books . . . and scattered those which they found, some over the level fields, others in the reed-bed of the marshes, and flung and hid others away in all sorts'of places.” They were afterwards found and taken to Fulda, where three of them are still shewn, viz. a New Testament, a book of the Gospels, said to have been written by the martyr himself, and a volume stained with his blood, containing, with other tracts of St. Ambrose, de Spirit'd S incto and Bono Mortis (Willibaldi Vita S. Bonif. xi. 37, and Mabillon’s note). In 799 Charlemagne founded an abbey at Charroux, which “ he en- riched with many relics and most munificent gifts brought to him from the east, and with a very rich library ’ (^Gallia Christiana, ii. 1278). Many monastic libraries were destroyed by fire in the 9th and following centuries, in several of which books must have been accumulating during a lengthened period. For example, in 870, when the Danes destroyed the minster of Medhamsted (Peterborough), founded about 656, “ a vast library of sacred books was burned with the charters of the monastery ” (Ann. Bened. iii. 167, § 16, from Ingulf.). In 892 the monastery at Teano, near Monte Cassino, was burned down, “ in which fire most of the deeds and instruments of the Cassinates were consumed, with the very autograph of the rule which the holy father Benedict had written with his own hand ” {ibid, p. 283, § 67). About the year 900, the Hun- garians destroyed the monastery of Nonantula by fire, and “ burned many books ” {ibid. 305, We can give no certain information on the origin and condition of monastic libraries in the east during the period to which we are confined. We may, however, infer vfith great probability that monasteries began very early to collect books, from the fact that manuscripts of the highest antiquity are found in them at the pre- sent day. About 400 volumes of MSS. are now in the British Museum, which were brought in the years 1839, 1842, 1847 from a single Syrian monastery, viz. that of St. Mary Deipara, in the Desert of Nitria, or Valley of Scete. As a proof of the antiquity of some of these books, we may mention that the thi’ee volumes in which occur the several copies of the Epistles of St. Ignatius published by Mr. Cureton are, one earlier than 550, another some 50 or 60 years later, and the third “ certainly not later than the 7th or 8th century ” {Corpus Ignatianum, Introd. xxvii. xxxiii.). In the second of these volumes Is a notice curiously similar to one quoted above i-especting an English abbat, to the effect that Moses of Nisibis, the superior of the monastery, “gave diligence ami acquired that book together with many others, being 250, many of which he purchased, and others were given to him by some persons as a blessing [see Eulosiae (5)], when he went to Bagdad ” (xxxi.). This bears date A.D. 931. The MS. bible found by Tischen- dorf (1844, 1859) in the monastery of St. Cathe- rine, on Mount Sinai, is assigned to the 4th century {Nov. Test. Sinait. Tisch. Proleg. ix.). He obtained many other books from the same library, and many from monasteries in Palestine, at Berytus, Laodicea, Smyrna, in Patmos, and at Constantinople {Notitia Edit. Cod. Sinait. p. 7). In his collection, now at St. Petersburg, are various Greek fragments of the 5th and 6th centuries {ibid. p. 56) ; five of tne New Testament of the 6th and 7th; and one of the 7th or 8th (p. 50): parts of some Homilies of St. Chrysostom (p. 55), and some liturgical remains of the 8th (p. 56); all in the same language; and a Syriac version of hymns and sermons by Gregory Nazianzen written in the 7th (p. 64). We do not multiply such facts, because, though A’^er}* probable indi- cations of the existence of monastic libraries in the East Avithin our period, and of the nature of their contents, they do not amount to a direct and positive proof. [W. E. S.] LIBRARIES. The word Hbrarius has two meanings—viz. either a ‘ book-seller ’ or a ‘ tran- scriber Ave are concerned Avith it in the latter sense. Of course there must have been tran- scribers in abundance before Christian times, if, as is said, the libraries of the Ptolemies at Alexandria, and of the kings of Pergamus in Asia Minor contained between them a million volume* and upwards in all languages (Dicr. of Gr. AND Rom. Ants. art. ‘ Bibliotheca ’). Tran- scribers Avere frequently slaves at first, or else worked for money, and were not Avell paid. Hence the endless complaints of their ignorance, carelessness, or dishonesty which occur in the Fathers as Avell as in classical authoi's (Wower, de Polymath, c. 18, ap. Gronov. Thes, x. 1079). But with Christian times the office of transcriber for libraries insensibly passed into better hands. It was not that he became, strictly speaking, a public functionary, but he copied far more fre- quently for ecclesiastical bodies than for private persons: and was, in most cases, a member of the body for which he worked. Thus he worked, not for money, but as a duty: and not on chance books, but on books carefully selected for their contents by his superiors. This altered the character of his performances materially, besides going far to ensure their preservation. It is a simple fact in history, that Christianity stands betAveen us and the written records of all preceding ages, and is our sole guarantee for their trustworthiness in their present state. Origen Avas one of the first Christians who is said to have employed transcribers regularly for literary purposes {fiifi\ioypd(f>ovs, Euseb. E. II. vi. 23). Alexander, bishop of Jerusalem, his friend and patron, was one of the first to form an episcopal library, Avhich Eusebius found of great use in collecting facts for his history {ib. c. 20). Eusebius himself, by order of the em- peror Constantine, had 50 choice copies of the scriptures made by experienced caligraphists on vellum, arranged in ternions and quater- nions {Vit. Const, iv. 34-7, and Vales, ad /.). Pamphilus, the presbyter and martyr, with Avhom Eusebius was so intimate, enriched Caesarea with a lai-ge library, consisting of the works of Origen and other ecclesiastical writers, tran- scribed by himself (ib. c. 32, comp. St. Hier. de Vir. Illust. s. v.): and it was still in exist- ence, and handy for readers, when St. Jeroma wrote. [Libraries.]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b2901007x_0001_1008.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)