Investigations in the relation between convergence and accommodation of the eyes / by Ernest E. Maddox.

- Ernest Edmund Maddox

- Date:

- [1886]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Investigations in the relation between convergence and accommodation of the eyes / by Ernest E. Maddox. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by UCL Library Services. The original may be consulted at UCL (University College London)

36/76 page 566

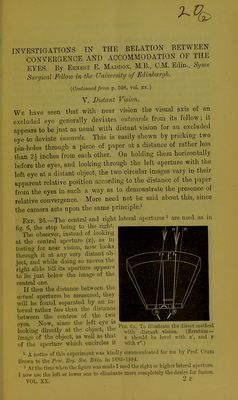

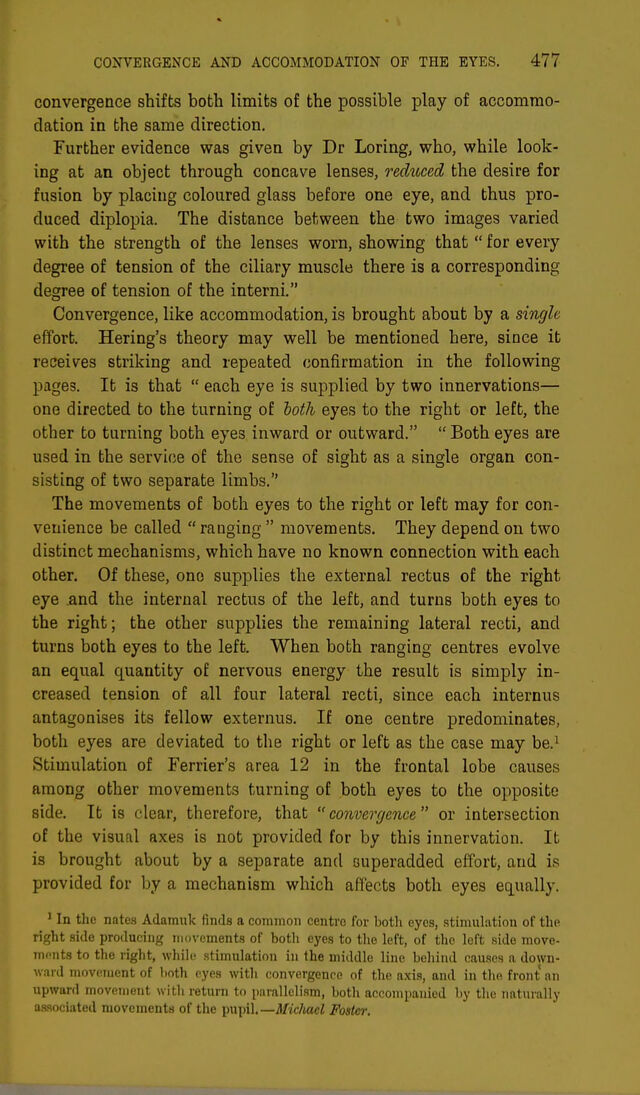

![as m a frame, must fall on the left fovea centralis or point of acutesi vision. The encircled image therefore is referred—where all fovoal images are referred—to the line which bisects the angle of convergence. But the other aperture has been placed so that its image appears to be in the same line, or rather slightly below if; it therefore must fall exactly above the right fovea, on the median vertical meridian of the right retina. Since each image falls on a median vertical meridian,0 it follows that if the apertures themselves were separated by an interval equal to the intercentral distance, the visual axes would be parallel; if the interval were greater there would be relative divergence, but as it is, the interval is less, showing relative convergence. Moreover, if, while the apertures are still kept in position, both eyes be made to observe distant objects through them, the images none the less appear superimposed; the amount of convergence attached to distant vision re- mains unaltered, whether one eye or both is used.1 Since the natural outflow of energy from the con- verging centre when the desire for fusion is absent is a delicate comparative index of the accommodating energy, this fact shows that the activity of the accorn° modating centre is no greater when both eyes are used than when vision is confined to one, and corro- borates the statement that accommodation is the work of a single innervation affecting both eyes equally at the same time. The object thus seen by the right eye, through the lower aperture, is one which really lies in a space to the left of the object seen by the left eye through the higher aperture. Thus, if in figs. 7 and 8, a and b are two distant objects, a is seen by the Fit!. 20. \a lb right eye through the lower Fir/. 2/. aperture, and b by the left eye through the higher one. Fig 9 shows that for this to occur the visual axes must cross some- where between the camera and the distant objects. This cross- ing point is at an average distance of about 112 inches from my own eyes. Another glance at figs. 7 and 8 will make it evident that for the same object (b) to be visible Fios. 7 ami 8.-Objects bY hoth eyes> the ]<>wer of the (a, b) seen through two apertures must be drawn °* ' the apertures of the away from its apparent position just under the camera- other to the right. Let this be done till b is visible in both apertures, the actual distance between them will 1 This presumes tho possession of eyes of eiiunl refraction.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b2163628x_0038.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)