Clinical diagnosis : the bacteriological, chemical, and microscopical evidence of disease / by Rudolf v. Jaksch ; translated from the second German edition by James Cagney ; with an appendix by Wm. Stirling.

- Cagney James.

- Date:

- 1890

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Clinical diagnosis : the bacteriological, chemical, and microscopical evidence of disease / by Rudolf v. Jaksch ; translated from the second German edition by James Cagney ; with an appendix by Wm. Stirling. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

45/432 (page 17)

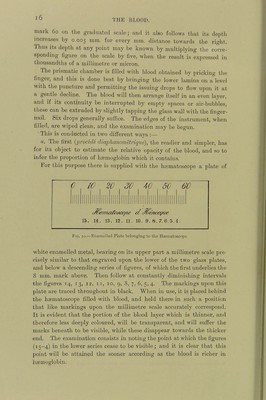

![Further, llenocque has arranged the series so that the second figure (14) expresses in grms. the quantity of oxylijcmoglobin in 100 grms. of blood, and this figure terminates the series as seen through a layer of blood of normal constitution. With blood taken from a case of anaemia, on the other hand, the figui’e 8 or 7 may be legible, and this implies that such blood contains in 100 grms. only 8 or 7 grms. of oxyhaemo- globin. Finally, the thickness of the stratum of blood at the point of requisite opacity may be ascertained from the mm. scale in the manner already indicated.* (/?.) In the second and more accurate mode of using the haemato- scojie the enamelled plate is dispensed with, and a Browning’s sjiectro- scope is required. The instrument, filled with blood as before, is placed opposite the cleft of the spectroscope, and the point is observed at which the characteristic spectrum of oxyhaemoglobin is first distinctly formed,—when the corresponding point on the millimetre scale of the glass plate is read off. The less haemoglobin in the blood, the thicke must be the layer from which a spectrum is obtained. In order to secure a correct reading from the scale, it is well to place the apparatus holding a stratum of blood upon a sheet of white paper against a window so as to examine it by bright and diffused daylight, and then directing the spectroscope over i or 2 cm. of its surface, the observer should several times judge for himself concerning the point of earliest defini- tion of the spectrum. Of the numbers obtained in this way (which will usually differ by an amount expressing only two or three millimetres) the mean is taken, and employed for the purpose of the calculation. It must be allowed that the conclusion in this respect is always some- what arbitrary, and leaves room for a difference of ojpinion as to when precisely the spectrum is formed; but once the eye has become ac- customed to look for a certain clearness in the outline of the bands, it . seeks for and easily appreciates it in every instance.! From the reading on the scale at the point where the spectrum is thus seen, the thickness of the blood stratum, and the quantity of oxyhaemoglobin in a known quantity of blood, can be readily deter- mined. In the case of normal blood, which contains 14 grms. of oxy- hsemoglobin in 100 grms. of the fluid, the absorption-bands are plainly visible in the situation of the figure 14 on the mm. scale; and from what * [Hcnocque’s haematoscope may be obtained from M. Lutz, 82 Boulevard Saiut* Germain, Baris. The price is 12 francs, and the enamelled plate costs 5 francs addi* tional.—(Ed.)] + [This difficulty may be further obviated by the use of Houocque’s double spectroscope, by means of which two persons are enabled to make the observation at once. Bor a description of this instrument the reader is referred to the original communication, *■ L’Hemato-spectroscope.” Compt. Rend;, fSoc. de Biologie, October 1886.]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21699574_0045.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)