Fermentation and its bearings on the phenomena of disease : a discourse delivered in the City Hall, Glasgow, October 19th 1876 : under the auspices of the Glasgow Science Lectures Association / by John Tyndall.

- John Tyndall

- Date:

- 1877

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Fermentation and its bearings on the phenomena of disease : a discourse delivered in the City Hall, Glasgow, October 19th 1876 : under the auspices of the Glasgow Science Lectures Association / by John Tyndall. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The University of Glasgow Library. The original may be consulted at The University of Glasgow Library.

10/40 (page 10)

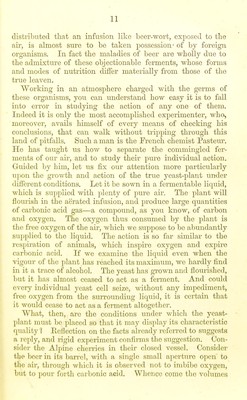

![Wiiat tlien is its true origin ? This is Pasteur's aus^yer, whicli Iris well-proved accuracy renders worthy of all confi- dence. At the time of the vintage microscopic particles are observed adherent, both to the outer surface of the grape and of the twigs which support the grape. Brush these particles into a capsule of pure water. It is rendered turbid by the dust. Examined by a microscope some of these minute particles are seen to present the appearance of organised cells. Instead of receiving them in water, let them be brushed into the pure inert juice of the gi'ape. Eorty-eight hours after this is done, our familiar Torulct is observed budding and sprouting, the growth of the plant being accompanied by all the other signs of active fermenta- tion. What is the inference to be drawn from this experi- ment 1 Obviously that the particles adherent to the external siu'face of the grape include the germs of that life which, after they have been sown in the juice, appears in such profusion. Wine is sometimes objected to on the groimd that fermentation is artificial; but we notice here the responsibility of nature. The ferment of the grape clings like a parasite to the surface of the grape, and the art of the wine-maker from time immemorial has consisted in bringing —and it may be added, ignorantly bringmg—two things thus closely associated by nature into actual contact with each other. Eor thousands of years, what has been done consciously by the brewer, has been done imconsciously by the wine-grower. The one has sown his leaven just as much us the othei'. Nor is it necessary to impregnate the beer-wort with yeast to provoke fermentation. Abandoned to the contact of our common air, it sooner or later ferments; but the chances are that the produce of that fermentation, instead of being agreeable, would be disgustuig to the taste. By a rare accident wo miglit get the true alcoholic fermentation, but the odds against obtaining it would be enormous. Pure air acting upon a lifeless liquid will never provoke fermentation; but our ordinary aii- is the vehicle of numberless germs which act as ferments when they fall into appropriate infusions. iSomo of them ])roduce acidity, some i)utrefactiou. _ The germs of our yeast-plant are also in the air; but so sparingly](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21450808_0012.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)