Intestinal obstruction; its varieties : with their pathology, diagnosis, and treatment.

- Sir Frederick Treves, 1st Baronet

- Date:

- 1899

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Intestinal obstruction; its varieties : with their pathology, diagnosis, and treatment. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library at Columbia University and Columbia University Libraries/Information Services, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library at Columbia University and Columbia University.

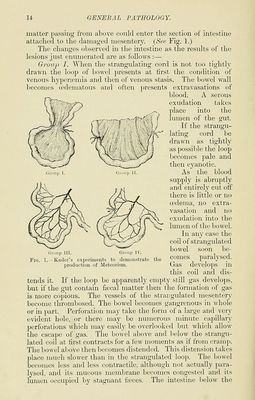

28/586 page 12

![the strangled coil. The snared bowel is tense, owing to the intiltration of its coats, and the distension of its cavity with gas. To the touch it feels thick and fleshy. Within the loop will be found, as a rule, only a little thin, dut3--looking fluid, w^hich in an instance or two may be stained with blood. Clots of blood haye been found wdthin the loop. Finally-—if the patient live lono- enoucrh—the bowel becomes ganoi-enous. It loses its elasticity, and feels soft and doughy. The gangrenous parts may be black in colour, but are more often ashen grey. The extent of the gangrene shows considerable variation, from a mere patch to the destruction of a considerable loop of gut. At a gangrenous point the gut may become per- forated. Special stress comes upon the bowel at the line of the actual constriction, and changes follow wdiich are identical with those met with in strangidated hernia. Linear gangrene is very apt to occur at this line. Under the influence of pressure the mucous membrane perishes first, then the muscular coat, and last of all the serous tunic. The effect of the strangulation is, as a rule, more marked in that end of the loop which is continuous with the bow^el above the line of constriction. It is by no means always easy to tell whether the strangulated gut is still living or is dead ; it is still more difficult to foretell that, althougdi damag-ed, it will recover. If the covering of the bowel retain its lustre, if the vessels in its walls can be seen to empty and refill on stroking, and if the gut bleeds when pricked, it is evidently still living. On the other hand, the lustre of the serous coat may soon be destroyed by inflammation, the individual vessels may be lost to view, and an extravasation of blood ma} have taken place at the point under examination. Mere de]3th of colour is not an infallible sign of the state of the gut. A loop almost black in colour may undergo complete recovery, while a like loop that is merely a bluish purple may give way after it has been liberated. The interpretation of the varied changes found in the intestine after occlusion of its lumen has been the subject of much discussion. It cannot yet be said that the pathology of the condition is to be explained in a manner which is entirely satisfactory. The causes of the changes found in the wall of the strangulated loop are not difficult to explain. It has been long ago pointed out that distension of a loop of intestine is](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21205516_0028.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)