On the development of the organization in phaenogamous plants / [M.J. Schleiden].

- Matthias Jacob Schleiden

- Date:

- 1838

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: On the development of the organization in phaenogamous plants / [M.J. Schleiden]. Source: Wellcome Collection.

32/40 page 26

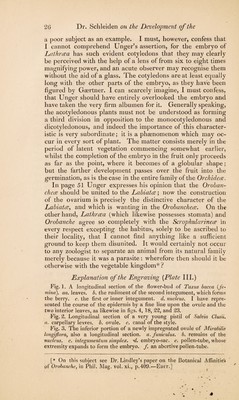

![a poor subject as an example. I must, however, confess that I cannot comprehend Unger’s assertion, for the embryo of jLathrcea has such evident cotyledons that they may clearly be perceived with the help of a lens of from six to eight times magnifying power, and an acute observer may recognise them without the aid of a glass. The cotyledons are at least equally long with the other parts of the embryo, as they have been figured by Gaertner. I can scarcely imagine, I must confess, that Unger should have entirely overlooked the embryo and have taken the very firm albumen for it. Generally speaking, the acotyledonous plants must not be understood as forming a third division in opposition to the monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous, and indeed the importance of this character¬ istic is very subordinate; it is a phenomenon which may oc¬ cur in every sort of plant. The matter consists merely in the period of latent vegetation commencing somewhat earlier, whilst the completion of the embryo in the fruit only proceeds as far as the point, where it becomes of a globular shape; but the farther development passes over the fruit into the germination, as is the case in the entire family of the Orchidece. In page 51 Unger expresses his opinion that the Oroban- chece should be united to the Labiatce; now the construction of the ovarium is precisely the distinctive character of the Labiatce, and which is wanting in the Oroibancliece. On the other hand, Lathrcea (which likewise possesses stomata) and Orobanche agree so completely with the Scrophularinece in every respect excepting the habitus, solely to be ascribed to their locality, that I cannot find anything like a sufficient ground to keep them disunited. It would certainly not occur to any zoologist to separate an animal from its natural family merely because it was a parasite: wherefore then should it be otherwise with the vegetable kingdom*? Explanation of the Engraving (Plate III.) Fig.l. A longitudinal section of the flower-bud of Taxus bacca (fe- mind), aa. leaves, b. the rudiment of the second integument, which forms the berry, c. the first or inner integument, d. nucleus. I have repre¬ sented the course of the epidermis by a fine line upon the ovule and the two interior leaves, as likewise in figs. 4, 18, 22, and 23. Fig. 2. Longitudinal section of a very young pistil of Salvia Clusii. a. carpellary leaves, b. ovule, c. canal of the style. Fig. 3. The inferior portion of a newly impregnated ovule of Mirabilis longifiora, also a longitudinal section, a. funiculus, b. remains of the nucleus, c. integumentum simplex. ~d. embryo-sac. e. pollen-tube, whose extremity expands to form the embryo, f. an abortive pollen-tube. [* On this subject see Dr. Lindley’s paper on the Botanical Affinities of Orobanche, in Phil. Mag. vol. xi., p.409.—Edit.]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b30379805_0032.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)