Report on a public local inquiry into an outbreak of typhoid fever at Croydon in October and November 1937.

- Date:

- 19

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Report on a public local inquiry into an outbreak of typhoid fever at Croydon in October and November 1937. Source: Wellcome Collection.

9/22 page 7

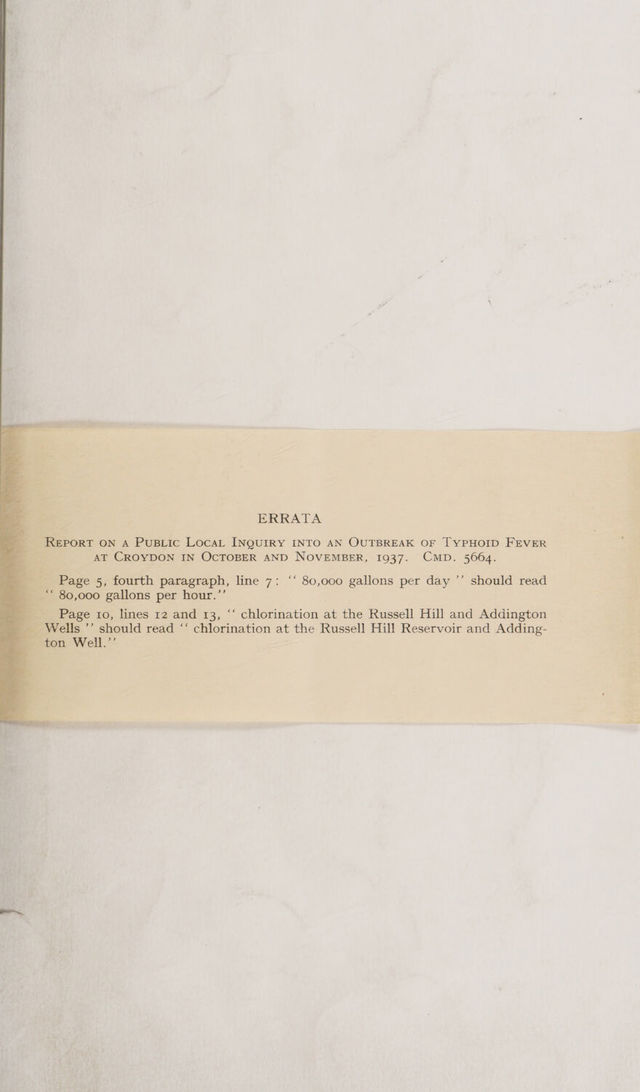

![intervals from 28th September to 26th October. It should be said of him at once that he was a man who had served in the war, had contracted typhoid in the war, and, through no fault of his own and in ignorance of the fact himself, remained a carrier of the bacillus. The period of incubation in the case of typhoid is variable and uncertain. It follows that the date of infection must always be conjectural. From the evidence I have heard given by eminent medical witnesses, I should say that the period of incubation in water-borne epidemics is not likely to be less than 14 days, that 21 days would be fairly common, and that the incubation period may be even longer. In fact, in this epidemic the one incubation period which was ascertainable with com- parative certainty was 23 days. But, whatever period be taken, the dates of the onset of symptoms point to the original infec- tion having taken place while the work was proceeding in the well and while the carrier was there. I have been supplied with charts, and I gratefully acknowledge the assistance I have derived from them, correlating the dates of the carrier’s presence in the well with the dates of notification of the disease, the dates of the onset of symptoms so far as ascertainable, and the dates of infection, taking different periods of incubation. They all enforce the same conclusion. That conclusion is supported by the views on probabilities expressed by every medical gentleman who appeared before me and who was aware that the presence of a carrier in the well at the material time had been ascertained. Although I have stated what is my definite conclusion as to the infection of the well, since it is one that cannot be arrived at with absolute certainty, I think it proper to deal with certain other possible sources of infection to which my attention was called. As these included farms where pigs and other livestock were bred it may be desirable if I] make one or two preliminary observations upon the typhoid bacillus in connection with such suggested sources of infection. Among the animal world it would appear that it is only in the human intestine that the typhoid bacillus lives. Removed from that environment and apart from certain special articles of food, such as milk or shell fish, its life is short. Five days was given me as an estimate of its length of life in a domestic water supply. Some writers on the subject place it a good deal lower. There is apparently no known case of a pig or other animal being an intestinal carrier of the bacillus. The short life of the bacillus once evacuated from the human intestine explains why, in addition to the invariable difficulty which exists, for various reasons, in isolating the typhoid bacillus from public water supplies, the carrier having ceased work in the well on 26th October. the bacillus could not be isolated after 3rd November. It also throws doubt upon the utility of looking for a possible source](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b32179236_0009.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)