First (-Second) report of the Royal Commission appointed to inquire into the subject of vaccination; with minutes of evidence and appendices.

- Great Britain. Royal Commission on Vaccination

- Date:

- 1889-1890

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: First (-Second) report of the Royal Commission appointed to inquire into the subject of vaccination; with minutes of evidence and appendices. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Library & Archives Service. The original may be consulted at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Library & Archives Service.

11/520 (page 3)

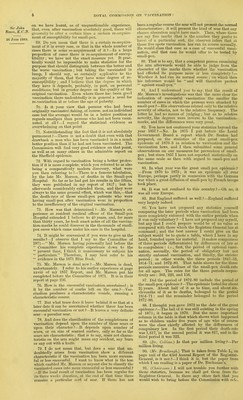

![52. At the time when you made the report, in the year 1857, compulsory vaccination had only just come into operation —It had begun four years previously. 53. It had begun too recently to enable you to f crm uny conclusion as to its effect .f—Quite so ; but now there is evidence on that branch of the subject. 54. But, prior to the introduction of compulsory vaccination at all—when there was only what I may call State-assisted vaccination —do you think that still there was a large reduction in the disease beyond what would have taken place if there had been no vaccina- tion ?—I think that is certain. I was able, in the year 1857, to quote the experience of other countries as well as that of England. 56. I believe some other countries are better supplied with statistics than we axe, their statistics having been properly kept at an earlier date ?—That is so. 66. I think, also, in some of the foreign armies there had been a very complete system of vaccination on a large scale, the results of which had been carefully collected ?—Yes. 57. Is there any specific illustration drawn from foreign countries to which you would like specially to direct the attention of the Commissioners ?—In the chapter about small-pox since the use of vaccination I referred to the case of Sweden; comparing with the 28 years before vaccination 40 years soon afterwards ; and I referred to some other foreign experiences. A pas- sage, in which some such references were mode, i.s this : During the earlier period there used to die of small- pox, out of each million of the Swedish population, 2,050 victims annually ; dtiring the latter period, out of each million of population, the small-pox deaths have annually averaged l.SB ; or compare two periods in Westphalia, during the years 1776-80, (I may observe that, now, I should consider that too short a period for comparison) the small-pox death rate was 2.G43 ; during the 35 years, 1816-50, it was only 114, '' Or taking together | from this table] the three lines which belong to Bohemia, Moravia, and Austrian Silesia, you find that where formerly (1777-1806). there died 4,000 a year, there now die 200. Or '■ taking two metropolitan cities; you find that in Copenhagen, for the half century, 1751-18uO. (here we get a good term of years) '■ the small-pox death rate was 3,128, but for the next half century only 286 ; and still better in Berlin, where for 24 years preceding the geueral use of vaccination, the small-pox death rate had been 3,422, for 40 years subsequently it has '• been only 176. In other words, the fatality of small- pox in Copenhagen is but an eleventh of what it was ; in SAveden little over a thirteenth ; in Berlin, and in large parts of Austria, but a twentieth ; in Wesr,- phaha, but a twenty-fifth In the last named instance, there now die of small-pox but four persons where formerly there died a hundred. 58. Have you any reason to suppose that statistics bringing the matter down to a later date, would show any substantially different result ?—I have no reason to suppose so. In one case there, a very short period was quoted, which as at present advised, I certainly should not quote, viz., a period of five years. Of course if a severe epidemic of small-pox fell in the time, it would make a disproportionate difference. 59. In most of the instances, I see that the term of years ranges from 20 years to hO years ?—Yes, that generally would be quite enough for compai-ison. 60. In this country what comparison are you able to make F - A very imperfect one ; but I say there : From '' such inforrtiation as exists, it seems probable that the small-pox death-rate of London within the Bills of Mortality during the eighteenth century ranged from 3,000 to 5,0u0. During the ten years 1846-55 it was under 340. 61. That was the latest ten years tbat you could take for yoiu- own report of 18.57 Yes, it was the latest I could get. But these masses of statistics are best under- stood, I think, when they are seen together with com- paratively small statistics. There were a good many smaller quantities of statistics that I quoted that are very valuable. Early in the century (1819) there was a little bit of evidence from Norwich which no doubt carried a great deal of conviction to people's minds. A very well- known and distinguished surgeon of that place observed minutely 112 infected families during an epidemic of small-pox, and published the results, which were these : The houses had 603 inmates ; there were 202 cases of small-pox, with 46 deaths. The 603 inmates consisted O .')9226. of three groups of persons : first, persons protected by Sir John previous small-pox were 297 (that was at the beginning Sinion, K.C.B. of the century,, and they had no new small-pox among them, and no deaths ; secondly, persons protected by 26 June I8t<9. vaccination were 91, and among them two caught small- pox, and none died ; 215 persons, that is to say, more than one-third of the population, were unprotected, and of those 215, 2u0 caught small-pox, and 46 died. There were abundant cases o'f that sort put before the public at that time on good testimony. Then, further, in those early days of vaccination, or in still earlier days, in the early Jennerian days, it was a matter of frequent occur- rence to test the result of a man's vaccination by inoculating him with small-pox afterwards, and there were plenty of cases of that sort in evidence that the man who had been vaccinated and was then tested with small-pox inoculation proved insusceptible of it. That was the land of evidence that there was then. 62. And that would be a severer test than merely coming in contact with persons having small-pox ?—■ Considerably more so. i 63. I observe in the statistics that you have just given us that nearly half the inhabitants of the infected houses appeared already to have had small-pox ?—Yes ; that was in 1819. 64. The disease at that time, if that is at all to be taken as a sample, must have been enormously preva- lent ?—Everybody expected small-pox in the last century, sooner or later. People would go on to a very advanced age in some cases without having- it, as they now go on sometime.s without getting measles or whooping cough ; but it was a common current contagion in the country, and sooner or later, I do not say everybody without exception, but nearly all people got it. For people who boasted I have not had small-pox, there was the phrase current—nemn ante oliittmi hcatus,—wait abit. Louis XV. died of a second attack of small-pox when he was an old man. 65. In the early days of vaccination, in the early part of the present century, the effects were, I understand, carefully watched ?—Very carefully. 66. There was at the time scepticism to be over- come ?—There were several sorts of scepticism There was apprehension that the vaccinated might have horns grow on them, but that did not fulfil itself. There were doubts as to the reality of the protection, and the doubts as to the reality of the protection were very severely tested ; but on that point I have a qualification, and a very important quahfication, to put in. In those early days there was a weak point which they could not know, and which, later in the century, began to show itself. They had assumed too easily, that the protection given would be a life long protection ; and as the century went on they found that it was not life- long in an absolute sense; that, while it was a great advantage to have been vaccinated in infancy in the sense of escaping attack, and while it was a still greater advantage in the sense of escaping death, yet it was not in either sense an absolute life-long protection. It became evident that in process of time the protection weakened itself ; and then came into vogue, first in Germany, first of all, I think, in the Wurtemburg Army, the practice of re-vaccination. 67. (Sir Edwin Galsworthy.) About what date was that ?—Frequent impermanence in the protectiveness of early vaccination had begun to be generally recog- nised in the twenties; and in 1829, systematic re- vaccination was begun in the Wurtemburg military service. At the same time with the growth of know- ledge as to the value of re-vaccination, there was advancing a new series of extremely important observa- tions as to the different degrees of protection that are given by different degi'ees of vaccination. These really were two new discoveries in the matter of vaccination ; and in estimating vaccination at the present day, one must have great regard to these two points. They were not, in the year 18.j7, as clear as they are now. My official successors know much more about them now than I knew in the year 1857. G8. <Chairman.) Do I correctly understand that the effect of what was ascertained was that vaccination in childhood did not always secure immunity, or that it never secured immunity, and always wore off?—It wore off in what, at that time, was an uncertain proportion of cases. In regard of what was then supposed to be a small minority of cases, there was hope that the propor- tion of failure represented only the proportion of bad vaccination; and that bad vaccination had a great influence in it I have no doubt; but as time has gone B](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21361332_0011.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)