Dictionary of English literature, being a comprehensive guide to English authors and their works / [William Davenport Adams].

- William Davenport Adams

- Date:

- [1879?]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Dictionary of English literature, being a comprehensive guide to English authors and their works / [William Davenport Adams]. Source: Wellcome Collection.

634/720 (page 626)

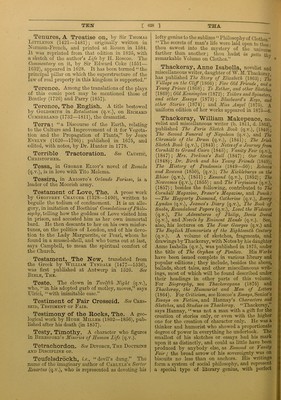

![TEW [ 026 ] TEW Tennyson, Alfred, Poet-laureate (b. 1809^, has published Poems by Two Brothers (with Ixis brother Charles Tennyson) (1827) ; Timbuctoo (1829); Poems, chiefly lyrical (1830); No More, Anacreontics, and A Fragment, in The Gem (1831); a Sonnet, in The Englishman!s Magazine (1831); a Sonnet, in Friendship's Offering (1832); Poems (1833); Stanzas, in The Tribute (1837) ; Poems (1842); The New Timon and the Poets, in Punch (1846) ; The Princess (1847) ; In Memoriam (1850); Stanzas, in The Keepsake (1851); Sonnet to IV. C. Macready, in The Household Narrative (1851); Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington (1852); The Third of February, in The Examiner (1852); The Charge of the Light Brigade, in The Examiner (1854); Maud, and other Poems (1855); Idylls of the King (Enid, Vivien, Elaine, Guinevere), (1859); The Grand- mother's Apology, in Once a Week (1859); Sea Dreams, in Macmillan's Magazine (1860); Tithonus, in The Cornhill Magazine (1860); The Sailor Boy, in The Victoria Regia (1861); Ode: May the First (1862); A Welcome (1863); Attempts at Classic Metres in Quan- tity, in The Cornhill Magazine (1863); Epitaph on the Duchess of Kent (1864); Enoch Arden (1864); The Holy Grail, and other Poems (1867); The Victim, in Good Words (1868); 1865—6, in Good Words (1868); A Spiteful Letter, in Once a Week (1868)) Wages, in Macmillan s Magazine (1868); Lucretius, in Macmil- lan' s Magazine (1869); The Window: or, Songs of the Wrens (1870); The Last Tournament, in The Contem- porary Review (1871); Gareth and Lynette, and other Poems (1872); Idylls of the King (complete), (1873); Queen Mary (1875), and Harold (1876). The fol- lowing poems have been attributed to him:—A Lover's Story (privately printed, 1833); Britons, guard your own, in The Examiner (1852);, Hands all Round, in The Examiner (1852), and Riflemen, form ! in The Times (1859). Separate notices of most of the above will be found under their respective headings. A Selection from the Works appeared in 1865; Songs from his Published Writings in 1871. A Pocket Edition of the Works was issued in 1869, a Library Edition in 1871—3, a Cabinet Edition in 1874, an Author's Edition in 1875, and an Imperial Library Edition in 1877. A Concordance to the Works was published in 1869. For the bibliography of Tennyson see Pennysoniana (1867). For Criticism, see Brimley’s Essays, A. H. Hallam’s Remains, AY. C. Boscoe’s Essays, Kingsley’s Mis- cellanies, Plutton’s Essays, Tavish’s Studies in Tenny- son, Bayne’s Essays, Austin’s Poetry of the Period, J. H. Stirling’s Essays, J. H. Ingram in The Dublin Afternoon Lectures, Forman’s Living Poets, Buchanan’s Master Spirits, and Stedman’s Victorian Poets. “ Mr. Tennyson,” says B. H. Hutton, “was an artist even before he was a poet; in other words, the eye for beauty, grace, and harmony of effect vMs even more emphatically one of his original gifts than the voice for poetical utterance itself. This, probably, it is which makes his very earliest pieces appear so full of effort, and sometimes even so full of affectation. They were elaborate attempts to embody what he saw, before the natural voice of tho poet had come to him. I think it possible* to trace not only a pre-poetic period in his art tho period of the Orianas, Owls, Mermans, &c. a period in which the poem on Recollections of the Arabian Nights seems to me the only one of real * interest, and that is a poem expressive of the luxurious sense of a gorgeous inward picture-gallery —but to date the period at which the soul was ‘ infused ’ into his poetry, and the brilliant exter- nal pictures became the dwelling-places of ger- minating poetic thoughts creating their own music. Curiously enough, tho first poem where there is any trace of those musings on the legends of the Bound Table [q.v.] to which he has directed so much of his maturcst genius, is also a confession that the poet was sick of the magic mirror of fancy and its picture-shadows, and was turning away from them to the poetry of human life. But even after the embryo period is past, even when Mr. Tennyson’s poems are uniformly moulded by an ‘infused’ soul, one not unfrequently notices the excess of the faculty of vision over the governing conception which moulds the vision, so that I think he is almost always most successful when his poem begins in a thought or a feeling, rather than from a picture or a narrative, for then the thought or feeling dominates and controls in otherwise too lavish fancy. AYhenever Mr. Tennyson’s pictorial fancy has had it in any degree in its power to run away with the guiding and controlling mind, the richness and the workmanship have to some extent overgrown the spiritual principle of his poems. I suppose it is in some respects this lavish strength of what may be called the bodily element in poetry, as dis- tinguished from the spiritual life and germ of it, which has given Mr. Tennyson at once his delight in great variety and richness of materials, and his profound reverence for the principle of spiritual order which can alone impress unity and purpose on the tropical luxuriance of natural gifts. It is obvious, for instance, that even in relation to natural scenery, what his poetical faculty delights in most are rich, luxuriant landscapes, in which either nature or man has accumulated a lavish variety of effects. There is nothing of AYords- worth’s passion for the bare wild scenery of the rugged North in his poems. It is in the scenery' of the mill, the garden, the chase, the down, the rich pastures, the harvest-field, the palace pleasure- grounds, the Lord of Burleigh’s fair domains, the luxuriant sylvan beauty7, bearing testimony7 to the careful hand of man, ‘the summer crisp with, shining woods,’ that Mr. Tennyson most delights. If he stray7s to rarer scenes it is almost always, in search of richer and more luxuriant loveliness, like the tropical splendours of Enoch Arden [q.v.], and. the enervating skies which cheated the Lotos-Eaters [q.v.] of their longing for home. There is always complexity in the beauty which fascinates Air. Ten- nyson most. And with the love of complexity7 comes, as a matter of course in a born artist, the love of the ordering faculty -which can give unity7 and harmony to complexity of detail. Measure and](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24861601_0634.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)