Volume 1

The cyclopædia of practical medicine : comprising treatises on the nature and treatment of diseases, materia medica and therapeutics, medical jurisprudence, etc. etc. / edited by John Forbes, Alexander Tweedie, John Conolly.

- Date:

- 1833-1835

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The cyclopædia of practical medicine : comprising treatises on the nature and treatment of diseases, materia medica and therapeutics, medical jurisprudence, etc. etc. / edited by John Forbes, Alexander Tweedie, John Conolly. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The University of Glasgow Library. The original may be consulted at The University of Glasgow Library.

49/850

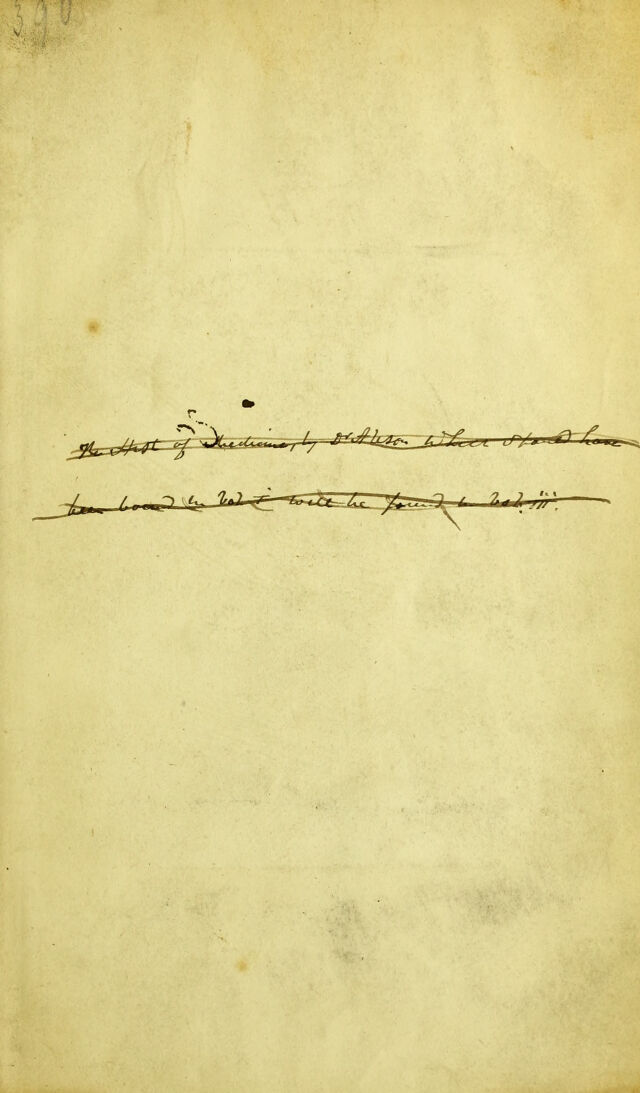

![what are justly and emphatically denominated the dark ages. Into these causes it is not our business to inquire; it may be sufficient to remark that they were of so uni- versal a nature as to operate on the human mind generally, and therefore to affect every intellectual pursuit. Medicine, among- others, felt their paralysing- influence, although, from certain incidental circumstances to be hereafter noticed, it was not allowed to remain so completely stationary as most of the other branches of science. About the period when Galen flourished, the Roman empire began to exhibit very decided symptoms of that decline which, proceeding with more or less rapidity, was never altogether suspended until it terminated in complete destruction. Even in the most splendid state of Rome, the cultivation of science was very limited, and we have had occasion to remark that almost all the physicians who acquired any considerable degree of celebrity were natives of Greece or Asia, and wrote in the Greek language. This was the case with Galen himself and with the few individuals who succeeded him, whose names are of sufficient importance to be introduced into this sketch. The medical writers of the third and fourth centuries have been characterized by Sprengel as de froids compilateurs, ou d'aveugles empiriques, ou de foibles imitateurs du medecin de Pergame.* The only exception to this remark is Sextus Empiricus, who appears to have been a contemporary of Galen, and probably derived his appellation from the sect to which he attached himself, as there are some treatises of his still extant in which he attacks the principles of the Dogmatists with considerable acuteness. We may conclude from his works that he was a man of learning and talents, well versed in the principles of the philosophers, and familiar with all the branches of literature and science which were cultivated in his time.f He is, however, the last medical writer to whom the character of Sprengel does not strictly apply. Oribasius, who lived in the fourth century, JEtius in the fifth, Alexander Trallianus in the sixth, and his contemporary Paulus, were all zealous Galenists, who professed to do little more than to illustrate or comment on the works of their great master. Their writings are principally compilations from their predecessors; they are, however, occasionally curious from the incidental facts which they contain, ano1 by furnishing us with extracts or abstracts of treatises which are no longer extant; but this constitutes almost their sole value. The only additions to the practice of medicine which they afford are an account of certain surgical operations, which is given us by iEtius, and a treatise by Paulus on midwifery, which is more complete than any that had previously appeared, and was long held in high estimation. But even these, which form but a small portion of the whole of their works, are con- nected with so much credulity and superstition, as to indicate at least the most degraded state of the science, if not the defective judgment of the writer. iEtius expressly recommended the use of magical arts and incantations, and that, not, as has sometimes been done in a more enlightened age, from a knowledge of the effect they might produce on the imagination of the patient, but apparently from his own opinion of their physical operation on the system.]; It must, however, be admitted that both in Alexander Trallianus and in Paulus we meet with various descriptions of disease, which indicate that they possessed the talent of accurate observation; and we may conclude that, although in what respects opinions they were the devoted followers of Galen, yet in the simple detail of facts their authority may be relied upon with considerable con- fidence^ With the death of Paulus, which took place about the middle of the seventh century, we may date the termination of the Greek school of medicine, for after his time we have no work written in this language which is possessed of any degree of merit. Those which occasionally appeared were mere servile transcripts of Galen and his disciples, or compilations formed without judgment or discernment, devoid of original observation, or even of any attempt at generalization or arrangement. In this degraded state was the science of medicine reduced in the former seats of learning, when a new school arose in a different quarter of the world, which will require our attention, from the actual * T. ii. p. 170. Jourdan's Transl. t Enfield, v. ii. p. 136. t Cottring, cap. 3, sect. 18-20. Sprengel, sect. 6, ch. 1-3. § Freind, Hist. Med. p. 39S et seq, and p. 420 et seq., Opera a Wigan, Lond. 1733. Eloy, Paul d'Egine. Haller, Bib. Med. t i. p. 311-15.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21462276_0001_0049.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)